Ariel Fristoe’s Community Theater Actually Changes Communities

Listen to the interview on Apple, Spotify, or your listening platform of choice. Captioned interviews are available on YouTube.

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For more than two decades, Ariel Fristoe has been at the center of one of the country’s most inventive experiments in how theater can live inside a community. As the artistic director of Atlanta’s Out of Hand Theater, she has shaped an organization known not for occupying traditional stages but for embedding performance inside civic life, partnering with schools, nonprofits, public agencies and neighborhood groups to spark dialogue and move people toward collective action.

Out of Hand’s work is now studied and replicated across the country, in part because it offers an alternative path at a moment when many arts organizations are searching for new models. Instead of focusing on season planning or ticket sales, Ariel and her team design programs that integrate theater with data, storytelling with civic participation and performance with tangible next steps for audiences who want to make change in their communities.

In this interview, Ariel reflects on how this approach emerged, how her own leadership evolved alongside it, and why she believes artists are uniquely equipped to work on the most urgent social issues of our time. She also gives a glimpse into Out of Hand’s next chapter — including a major 2026 national initiative — and shares what she’s learned about building trust, building partnerships and sustaining purpose-driven work over the long haul.

Pier Carlo Talenti: I’d love to know the Out of Hand origin story please.

Ariel Fristoe: Back in 2001, when my best friend and my now-husband and I started this company together, we realized even back then that there were already plenty of great theater companies in Atlanta. Atlanta did not need another theater company, and we would never be able to compete with the Alliance, Atlanta’s big theater company, or Broadway at the Fox touring shows in things like budget size or star power. So we made a conscious decision from the beginning that we should make sure never to try to compete for those things and that instead we would only make work about the issues that were most important to us and our neighbors.

We took our programs as often as possible into the community, into spaces where people are already gathered and where they feel comfortable, because we realized even back then that most people don’t go to the theater. A lot of people won’t go even if you give them a free ticket. We were really interested in making the audience an active part of our programs, making them social events, giving the audience different kinds of roles to play.

So all that was from the beginning. We did a bunch of really fun, wild stuff that was a lot about getting younger adults like us interested and excited about theater.

Pier Carlo: What was your favorite project from those years?

Ariel: Oh, gosh, there were so many.

Pier Carlo: The one in which you felt you really hit all your points, succeeded on all the levels you intended.

Ariel: OK. Amazingly there were several, but in terms of getting young people excited, there was this one called “30 Below” that was a show for, by and about people under 30. The show was like a rock concert. It was this two-story stage that was covered with plagiarized corporate logos, and it was basically about Gen X and younger, how we grew up on MTV and commercials and we were kind of apathetic young adults. And what really resonated with us was stuff like jingles.

It was this wild interactive thing where when you entered, you had to be patted down and go through a security check, which in 2001 was not a regular occurrence in this country. Then you would have to register your cell phone, and then we would take some people away for further inquiry. But really what we did was we were selecting people to be part of this one short piece in it where we would call people’s cell phones, purposely ask them to leave them on, and then audience members would answer their phones much to the dismay of their friends, their dates who were like, “Oh my god, what are you doing? Put that down.” And then they became part of the show and they’d wander up onstage and be carrying on conversations.

And then it turned into this whole musical theater number about live performance.

Pier Carlo: Wow.

Ariel: Yeah, it had all of these goofy musical numbers in it.

Pier Carlo: And young people showed up?

Ariel: Yeah, it was this wild experience where of course we had a good house for opening night because it’s our friends, and then the Sunday of opening weekend, we had five people in the audience in a 200-seat house and one of them was a critic. And we were like, “Oh my god, it’s a flop.” And then we got these amazing reviews, and then we were sold out for like the last three weeks of the run with people sitting in the aisles. We were letting people in who the fire code I’m sure said we shouldn’t be letting in. There were people dancing in the aisles in this wonderful, crazy rock-concert party atmosphere with smoke machines and pop music, and it was a lot of fun.

We then did collaborations with scientists for a while about communicating scientific research to non-science audiences, to general audiences, some of which was funded by the NSF and NASA. Then what happened is my husband, Adam, and I got married and we built a house on an empty lot in the Martin Luther King Historic District, which geographically is right in the middle of Atlanta. My husband is white, so am I, and we were the white people who thought some about, “OK, what does it mean to be moving into — in this case — not just any historically Black neighborhood but an incredibly important historically Black neighborhood?”

One of the first things we thought was, “Well, OK, let’s send our daughter and our foster kids” — we were foster parents for many years — “to our neighborhood elementary school, which is a couple blocks away.” Like many Atlanta public schools, it is a school where over 99% of the kids are Black and over 99% of them are living in poverty, because our little part of the neighborhood also abuts one of the largest subsidized housing developments in the Southeast.

So it was really that. It was getting inside that school as progressive white people. I had been raised by a single mom on food stamps and lived in subsidized housing myself, but still, that white poverty did not look anything like what this looked like. I think that probably most white people have not spent significant time in schools like that. It was like, oh my goodness, I had no idea how alive and well segregation was and how entrenched and enormous systemic racism is in this country.

So we thought, “OK, well, we can continue to make theater at Out of Hand about any community issue, but we’re right here in the King District. The most important thing to do with the rest of our careers is to help eradicate racism, violence and poverty, the three evils identified by Dr. King as the barriers to building the Beloved Community.” So that is what we have done ever since for the past 15 years.

Pier Carlo: So how did you go about getting your ducks in a row for that particular pivot? Because that’s a tall order right there.

Ariel: [She laughs.] Yeah. Yeah, so we started with doing some listening sessions and some programs with and for our neighbors.

Pier Carlo: Right, because the danger of course is that, oh, perhaps your community doesn’t want this at all.

Ariel: Oh, absolutely. Yeah. So just listening sessions, community meals with some fun arts-based activities and some arts-based data-gathering methods to find out what our neighbors care about. What are they worried about? What are their hopes and dreams? What are they interested in? How do they feel about us? That led to a number of other programs.

Then regarding the school that we were involved in, Hope Hill, I went to the principal of that school, to the office of my local city council member and to a few other key local community leaders and said: “Hey, I’m an arts leader. I don’t have a lot to offer you. I wish I had some other things to offer you, but would you have any interest in an after-school theater program? I don’t want to build and try to give you something that is not useful to you or that you don’t want, but is there anything I could make for you that you would like or you’d be interested in? And can I help you write some grants?”

And they said: “Yeah, actually there’s this research that shows that arts education, particularly for kids who don’t have all these advantages of being in wealthy families and wealthy schools, increases attendance rates, test scores, grades, graduation rates, things like literacy. And what we really need is to help these kids disrupt cycles of poverty by getting and keeping good, paying jobs. So can you build a theater program that will help kids with the soft skills that you need for that that aren’t taught in high school? Collaboration, communication skills, creative problem solving and confidence.” And I was like, “Oh my gosh, those are exactly the four things you need to make theater.” I was like, “Yeah, done. Done and done.”

We started our kids’ program there and we now provide over 550 free theater classes to over 450 kids at schools just like that. I think it’s eight or nine schools that we’re serving this year. It’s just one of our programs.

Pier Carlo: Wow, that’s incredible. You described yourself as an arts leader. As you developed your artistry, did you consciously also develop your leadership skills, or did that come naturally?

Ariel: Oh, no, I absolutely did. For one thing, we had a really small staff for a long time, and so I didn’t even know that I didn’t know how to be a manager because I wasn’t really one. I didn’t have anybody I had to manage in particular, given the staff of three or four.

And then, honestly, what happened is … . So my husband, Adam, and I ran this company together for about 15 years. My best friend, who I’d also started it with, left long before that; she went to graduate school in England and went on to other things. But then after 15 years, my husband said, “Hey, I’m going to take a job as a full-time professor of theater.” We’re still married and it turned out great, but that was the moment where I went like, “Oh, no. What am I going to do? I’m alone. I’ve always had a partner.”

I thought, “OK, well, I talk a really good game about all the impact that I want to make, that I want to have in these community issues, but we’re tiny. We have a staff of three and a half and a budget of $300,000 a year, and we’ve been at this for 15 years. If we’re ever going to have this kind of impact, we’ve got to grow.” So I purposely set about to do all of the leadership programs that I could find and to make friends with and be a known quantity among the decision makers and community leaders in Atlanta. And to prove that the arts are valuable collaborators when you’re trying to address community issues, that we should be sought out and we should have seats at the table as collaborators.

Every single program we do is a community collaboration with at least one partner organization, sometimes many, and they are designed to serve their goals. Our goals are sort of served secondarily by serving our partners’ goals through the arts. Arts and entertainment are not actually our primary goals. Our primary goal is social impact, and theater is one of the primary tools we use for social impact, but it’s not the only one.

Pier Carlo: How big is your staff now?

Ariel: It’s nine, and our revenue last year was just under $2 million.

Pier Carlo: Wow. And how many people on your board?

Ariel: I think 25 on the board and then another 45 on our advisory board.

Pier Carlo: Wow, so it’s a big organization. And you’ve purposefully, I think, not bought or rented a space. Was that to keep costs down?

Ariel: Well, no, we have turned them down before, and costs are not necessarily the most important reason not to have a space. For us, the most important reason not to operate a venue is because we can’t reach the people we need to reach at a traditional venue. In order to reach the people we want to reach, we have to bring our programs to them.

Pier Carlo: I want to hear about Equitable Dinners now. Of course, you’re not the first artist I’ve talked to who does a version of breaking bread with members of the community. First, why do you think theater artists are the perfect people to host such dinners?

Ariel: They do not host them.

Pier Carlo: Oh, you don’t?

Ariel: No. Actually, every single program that Out of Hand does is hosted by someone who is not us. That’s one of our magic-recipe ingredients: We are never the hosts of our own programs. That means that the people who come were all invited by someone who is not a theater company. People come to our events not even knowing what the topic is. They come because their neighbor or their coworker invited them, or someone’s kid goes to school with their kid.

Pier Carlo: So tell me how I’d experience it. Let’s say I get an invitation from a neighbor to go to an Equitable Dinner that’s taking place at her house. What would I experience?

Ariel: Actually, we less do Equitable Dinners in people’s homes now and more in larger community venues. We do have another program we do always in people’s homes that’s literally called Shows in Homes. But either way, everything that we do follows the same recipe that we have, which is, “Art to open hearts, information to open minds, and conversation to inspire action.” Those are the three critical pieces of everything we do.

We never just produce a play. There is always theater, and it has to be really good quality theater in order for it to work, to have its intended goals, but the reason that theater artists are the right people to organize these and use them is that we have the ability to take really messy, complicated, mind-numbing data on community issues and turn it into entertaining, emotionally engaging stories that makes that data sticky and memorable. That is what we do with all of our programs.

But we don’t want people to ever make the mistake of thinking, “That was just a story,” so we also have to give them a little bit of the data so that they see why we made the story about it and don’t just think it was for entertainment only. Then while they are still in the room with the art and the information, we invite them to process that, process the facts they learned, the feelings they had, and commit to taking action when they leave the room. Because otherwise, if we don’t have that really important conversation element, people will walk out the door, look at their phones, get distracted, and maybe never think about it again. Instead, what we want them to do is process that out loud and then choose from usually three actions that our community partners propose — we ask them to propose — that you can take when you leave in the next one to four weeks to actually move the needle on that issue.

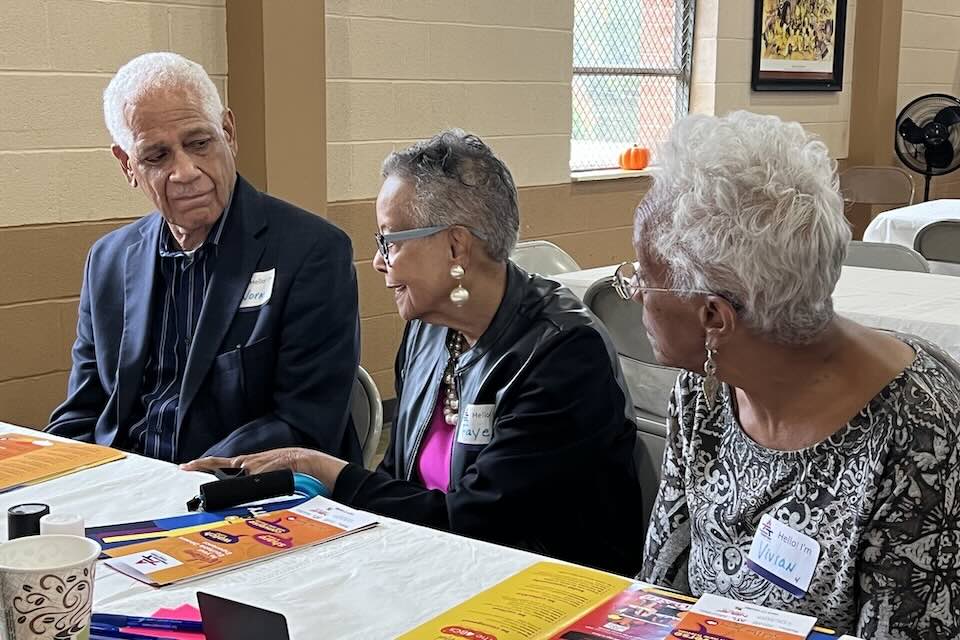

Thriving Together Atlanta Equitable Dinners event at Hillside Presbyterian Church. Photo: Out of Hand staff

Pier Carlo: I’m sure you talk about some very hot-button issues that impact the different communities you work with throughout Atlanta. How much room is there for disagreement?

Ariel: Yeah, there is all the room in the world for disagreement, but there is no room for hate or blame or hopelessness. We use professional facilitators for lots of our programs to facilitate those conversations that are the last important ingredient.

Pier Carlo: So if I went, I would experience a theatrical event —

Ariel: Oh, yeah, sorry, I didn’t answer that. Yes. So you arrive at someone’s home, and you get greeted. It’s either a cocktail party or a meal, so you probably get asked what you’d like to drink and given some snacks. You meet some other people, and then you sit down and watch a play that lasts between 10 minutes and an hour but no more, depending on which format we’re using.

Then there is a community conversation, either around dinner tables in groups of eight or 10 with a facilitator at your table or just 30 people gathered in a living room, where you get to hear from someone from the organization that works on homelessness or immigration detention or divisive concepts and classroom censorship or health equity or whatever program it is that we’re doing that day. They get to tell you about the data, their organization, what they’re working on and what they need, what they need help with. And you get to ask questions and share your thoughts. Then you have maybe another glass of wine, a few more snacks, mingle some, there’s a social time, and then you go home.

Pier Carlo: And I imagine you make it easy for people to act on what they’ve learned?

Ariel: Yeah. What we always try to do is ask our community partners to suggest three fairly easy actions so that each guest can choose one that they will take in the next month. Things like voting or registering to vote or looking up what a law is in your locality or participating in a local strategic planning process as part of that with your local government or volunteering or going to an event hosted by a nonprofit that works on that issue. Something simple like that.

Pier Carlo: What’s your favorite thing that you’ve heard from participants?

Ariel: In 2019, we did this program that launched those Equitable Dinners where we gathered 1,000 people at 100 dinner tables. This was in people’s homes, literally in their dining rooms all across this small city called Decatur that’s right next to Atlanta. Back then, we had no idea if we could get 1,000 people to do this.

Pier Carlo: Why Decatur?

Ariel: The year before, one of the “Shows in Homes” performances was in Decatur, and that night, the subject of that play led to a late-night discussion about experiences of racial discrimination against Black people in Decatur. That is what caused us to do this. So the conversation at every table at Decatur Dinners was about racial justice in Decatur, launched by a 10-minute play about the experience of being Black in Decatur. Yeah, so like, “How many people are going to be willing to do that, even though it’s free, it’s potluck dinners … ?”

Pier Carlo: And also how do you ensure that there’s a representative racial mix in your participants, right?

Ariel: Right. We asked people to go to strangers’ homes. We were asking 1,000 people to sign up and “Tell us about your race and gender, and are you allergic to cats? Are you a vegetarian?” And a little bit of other information. “Is there anyone who you want to make sure you are with? Do you want to make sure you’re with your sister, your wife?” And then we assigned all of those people to go to strangers’ homes, knowing maybe only one or two or no other people there, in order to have racially diverse conversations that night.

Then what happened, wonderfully, was 1,400 people signed up for 1,000 spots. We made space for 1,200 people, and in the year that followed, that city reported to us that a record number of people participated in the city’s strategic planning process and a record number of people of color both ran for and were elected to local office.

Pier Carlo: Ariel, that’s incredible.

Ariel: Yeah. Thank you. Yeah, it’s really fun, doing what I do. I’m really lucky to get to do something that works as well as it does, especially at a time when so many arts organizations are suffering.

Pier Carlo: How do you manage it? It sounds like an incredible amount of work.

Ariel: [She laughs.]

Pier Carlo: I imagine you’ve gathered a good staff, but how do you keep going?

Ariel: Well, I think it’s because I really am on a mission to put artists everywhere to work for social impact. My alarm clock goes off at 7 in the morning, and that’s the first thought in my mind. I get up and I go, “OK, how do we move the needle today? What can my organization do? All the plans that we have, how do we move forward on those?” But also, “How do I continue to spread the word to other arts organizations, to funders, to community leaders who might want to partner with arts organizations in communities all across the country?”

That is so exciting for me. It is wonderful to have a life that is so filled with purpose and meaning that that gives me a lot of energy.

Pier Carlo: You’ve partnered with corporations and other organizations in the past. I’m wondering if that has ever created issues when a corporation was not entirely on board with your social justice vision.

Ariel: Well, I will say there was one grant that we got, an unsolicited grant, that we turned down because we thought, “Oh, the goals of this organization are just so misaligned with ours that this does not make any sense.” There is a line, and we did see it.

In terms of working with corporations, I’m the artistic director of Out Of Hand, and I’m in effect a co-executive director. My co-executive director, Adria, her title is Activism Director, but she is the DEI professional, she is the professional dialogue facilitator and she’s also our business leader, in effect, our managing director. I and several other people asked her many times right after the summer of racial reckoning, George Floyd, all of that, when suddenly Coca-Cola and Mercedes Benz and UPS and all these big corporations headquartered in Atlanta wanted to hire us, “Adria, how do you feel about this? Do we ... ?” And she said, “Absolutely, yes. What they’re asking us to do is to do a program for 100 or however many of their managers, their leaders, to help them know more, care more and do more about this issue. Do we want that? Yes, we absolutely want that.”

Pier Carlo: And now it’s five years later, and it’s a very different climate. How are you both dealing with this new era?

Ariel: Yeah. So the spring was rough. We got DOGE’d, like so many other people. We had a million-dollar contract with the Georgia Department of Public Health for a statewide vaccine-confidence program that we’d been doing for four years with them. Actually, two separate programs: one in English, one in Spanish, one built for and with rural Black communities, one for Hispanic and Latino communities —

Pier Carlo: Which I’m sure you’d been planning for years.

Ariel: Oh, we’d been doing it for years. This was the fourth year that we’d been doing it, with new artistic assets and program tweaks every year. The CDC was one of our main partners as well as the Department of Public Health. They were the subject matter experts and helped us craft the messaging every year.

And back in the spring we got a letter that said, “Your contract has been canceled as of yesterday.” Then for a little while, it seemed like corporations were just frozen, and nobody knew what the future held, so nobody could make a decision. We thought, “Oh my gosh, are people still going to be willing to hire us and partner with us?”

The good news is yes. It’s different. We’re actually doing a lot more work with local government entities hiring us and universities still hiring us and partnering with us and of course, issue-based nonprofits and social justice nonprofits. Not as much corporate work. The mix is different, but we are really excited to see how many of those other organizations are still excited about partnering with us.

In 2026, one of our programs — it’s actually the Equitable Dinners format for 2026 — is a program called “We Hold These Truths,” as in, of course, “We hold these truths to be self-evident.” 2026 is the 250th anniversary of the Declaration of Independence. There will be a lot of celebrations of this around the country, and we are part of a national coalition of over 500 organizations across the country looking to bridge divides in American life and to commemorate this event in a way that is really inclusive of all American stories.

For us here, it was really important that this not just be like an urban-core-of-Atlanta in-town conversation about “What is your truth? What’s your experience of American democracy past and present, and what are your hopes and dreams for the future?” We think the most important audience to reach is the vast suburban audience outside of the literal city of Atlanta. It has been so exciting for me how many suburban mayors, county commissioners and city council members have said yes and signed on to being partners on this program.

Pier Carlo: Really? Because my understanding is that Georgia’s maybe a little bit like my home state of North Carolina in that it’s nominally purple, but you have blue urban dots and very red suburban to rural sections.

Ariel: Exactly. Yes.

Pier Carlo: I’m hearing, though, that some perhaps red civic leaders are saying, “We want to work with you.”

Ariel: Yeah, it’s been interesting. In the suburbs of Atlanta, there are a number of mayors and county commissioners and city council members who do lean more progressive than conservative. It bleeds out from the center of Atlanta. But some of them are literally Republicans who are signing up and saying, “Yes, of course we want to have this conversation in our community about ‘Let’s get together and talk about American democracy and what truths are you holding onto and let’s bridge divides and build a better future together.’”

Pier Carlo: That’s fantastic. So has that already started?

Ariel: We actually have four playwrights for this. We’ve got four different American experiences that you can launch your event with. We just hired them and did the kickoff meetings for them to go start doing research and listening sessions and then writing.

Pier Carlo: So these four playwrights are going to go to different suburban areas of Atlanta and do listening sessions and then write their plays?

Ariel: Yes, although they are representing four different aspects of the American experience rather than four different geographical areas of Atlanta. The four are someone whose ancestors immigrated to the Atlanta area — or really to what was rural and is now suburbs outside of Atlanta — from Europe many generations ago. That’s the first perspective. And what has happened to the American dream. The second perspective is someone who’s descended from enslaved people in the South. The third one is a Native American perspective on American democracy — past, present, and future. And the fourth one is a perspective of a very recent immigrant from Latin America.

[Laughing] We’re trying to do it sort of like the movie “Clue” from the ’80s where we encourage people to collect them all. Or if you can’t, at least go to a different one than your friend and then trade stories afterwards.

Pier Carlo: That’s amazing. Let’s say somebody is hearing this and says, “Oh, I want to do what Out of Hand is doing in my community.” What are the first steps?

Ariel: First of all, yes, please. Please do that. For anyone who wants to do Equitable Dinners, including “We Hold These Truths,” we license Equitable Dinners and this specific program, with or without our plays, to arts organizations and community groups anywhere in the country who want to do them. Equitable Dinners happened last year in Minneapolis, organized by Mixed Blood Theater, and it’s happening again this season in Minneapolis and now also in Pittsburgh for sure. And then there are some other communities who are deciding right now whether or not they can do it.

So yeah, email me or call me and we’ll talk and I will help you make it happen.

Pier Carlo: Lastly, as a theater lover, do you have a prescription for how to bring people back into theaters?

Ariel: Yeah. I think that so many theaters are leaning into the idea of, “Well, labor costs and material costs are rising at the same time that audiences and public support are declining. It’s a perfect storm; it’s terrible. What we need to do is program the most popular, fun shows. Let’s make the musicals that we can that have traditionally been our biggest sellers.”

Pier Carlo: Commit to entertainment with a capital E.

Ariel: Exactly. And if that worked, that would be awesome. But it is not working. That is not enough. Costs are still rising, and audiences are still declining in most places.

There could be multiple answers, but the one answer that I know that really works is use your skills as an artist to work with and for your community. Make work that is hyper-local, that will bring people in even if they don’t care about art, bring them in because they care about your community partner organization or about the issue.

And take advantage of the fact that you are producing live art to make your programs social events where people connect to feel connected, where they feel a sense of social cohesion, because there’s an epidemic of loneliness in this country and a mental health epidemic. And here we are opening our doors and letting people often walk in and sit in the dark and walk out without having ever talked to anyone except maybe the person who took their ticket. We are losing out on a golden opportunity of having people gathered together.

December 10, 2025