dots

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

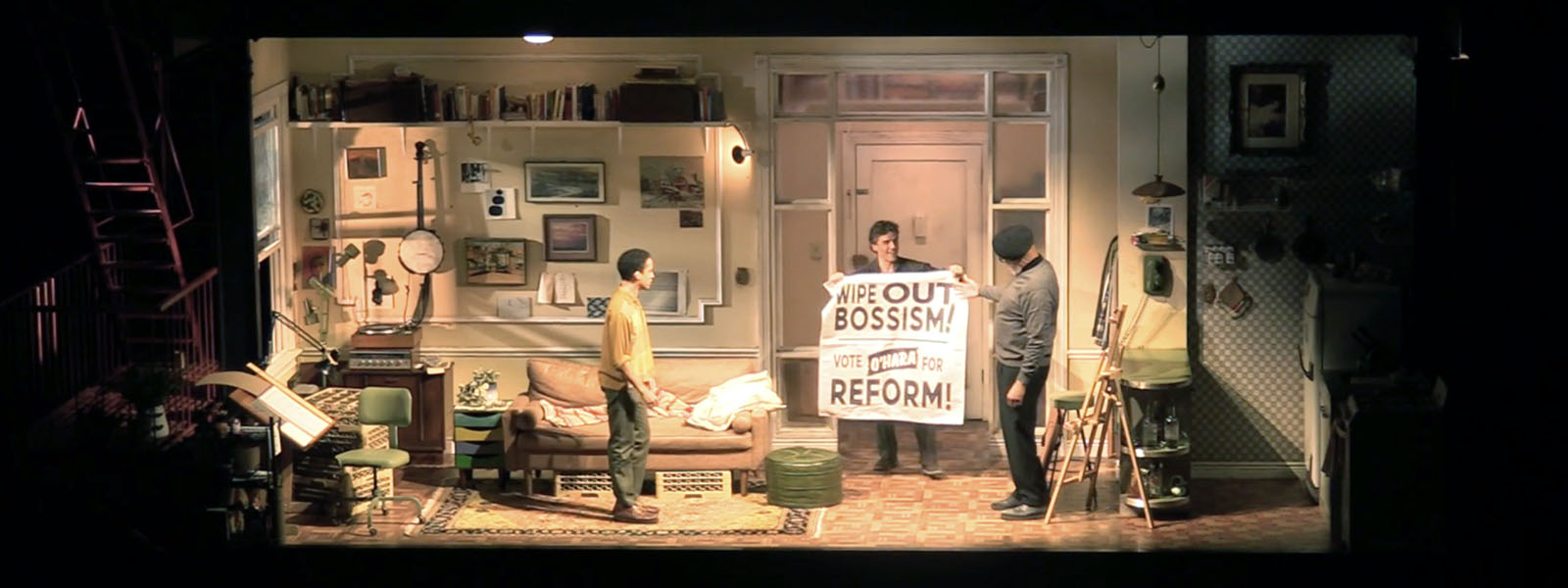

Perhaps the hottest ticket on Broadway right now is to the starry revival of Lorraine Hansberry’s play “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window,” starring Oscar Isaac and Rachel Brosnahan. Should you be lucky enough to score that ticket, you will find an unusual credit in the Playbill: scenic design by dots.

Barely two years old, dots is a collective of three talented international designers who decided soon after earning their MFA’s at NYU to create a unique partnership. They are Andrew Moerdyk, who hails from South Africa; Kimie Nishikawa, born in Japan; and Santiago Orjuela-Laverde, a native of Colombia.

Their partnership, truly unique in the American theater, is clearly paying off. Not only are they about to make their Broadway debut at a very early stage in their respective careers but their work has also been seen in some of the highest-profile theatrical projects of recent months, including “Dark Disabled Stories” at the Public Theater and Elevator Repair Service’s “Seagull.”

In this episode, the three designers explain how they developed the initial idea for their partnership during the pandemic lockdown and describe how the stability the collaboration provides more than makes up for no longer seeing their individual names in the production credits.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- What was the initial idea for dots, and how did you go about developing the blueprint of what it would be?

- In what way would you like institutions to change? And given that that change is not happening, how are you with your collaboration handling that reality?

- Do you miss seeing your name in the credits?

- What does the name dots signify?

- Have the three of you in this collective built in time for creative imagining?

- Could you talk about a recent project and how you discussed it and then apportioned the work?

- In your business model you’re there for each other … It seems like such an obvious model to me, and so I’m surprised that there’s not more like it. Why do you think that is?

- How long did it take to develop for the three of you?

- Can you talk about hitting an artistic roadblock in a design and how you would not have gotten through it without the help of your partners?

- Do you have thoughts about what could be changed or reinvented at any level so that someone following in your footsteps could more easily form the kind of partnership that you have? Or even what could make it easier for you to keep doing what you’re doing going forward?

- I know that clearly you have strong relationships with directors and directors get what you’re doing. Have you gotten any resistance from institutions?

- I wonder if you could talk about any upcoming projects that you’re particularly excited about after “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window.” And that you can share.

Pier Carlo Talenti: What was the initial idea for dots, and how did you go about developing the blueprint of what it would be?

Santiago Orjuela-Laverde: I think the gathering together was the first part. The three of us chose to stay in New York when the pandemic hit, and I think the free time became real. We had a chance to spend time together, not thinking about the work we needed to do. It was more about how we dealt with the work in the past. I think that moment of quietness in the industry was very helpful for us to see in perspective what was happening, what we weren’t really happy about. Then it became a very beautiful, necessary brainstorming which, I want to say, came from the casualness of just hanging on my rooftop and drinking a beer and looking at sunsets, literally.

Andrew Moerdyk: Yeah, it was just that moment. It was just a pause, and we really took advantage of the time to reflect that was thrust upon us, which was really helpful. And then we discovered that we were all kind of feeling the same way.

Pier Carlo: Could you describe what you were feeling?

Kimie Nishikawa: We were definitely exhausted and also broke, I think [they all agree and chuckle]. I think … Andrew, you’ve said this so well, it was this question of, why are we competing with each other? Because it’s usually, “Who’s designing that show?” or “Who’s doing what?” It’s all about the individual names, and I think that’s quite toxic.

So we were really talking about how can we first not really credit our own individual names on everything we do and collaborate on a lot of things. People don’t need to know how the sausage is made, I guess. We wanted to … what’s that word we were using? Agency.

Andrew: Yeah.

Kimie: We wanted free agency for ourselves, because in a bleak way I didn’t quite believe that the industry would really change. So then how can we change how we offer ourselves to these institutions?

Pier Carlo: I want to hear more about that. In what way would you like institutions to change? And given that that change is not happening, how are you with your collaboration handling that reality?

Kimie: I just think a lot of institutions don’t quite understand what it takes for design to happen. A lot of the time, as professionals, we want to make it look easy, of course, but there’s so much involved in producing a final product, and it’s so much for one person. It actually can’t be done as an individual. Even set designers or other designers usually have many assistants or associates. The acknowledgement of “This is actually a lot of work for one person” is a great way to start, I think, but I don’t think that will happen.

Andrew: It is too big a job for one person to do, and the way that the current system works is that the team gets a little bit forgotten about. I think that’s also a situation that all three of us had been in, where you work really hard on something for someone else to get all the credit or to meet the directors or whatever. It just opens the door to gatekeeping. Yeah, it just doesn’t feel reflective of the way the world works now and of the people that are doing the work now.

Santiago: Yeah. Also I would add to that, when we talk about this, we pretty often use a metaphor of an umbrella that takes care of us. I feel like when we talked about creating that agency, it was also creating this umbrella to help us navigate different situations. When I say an umbrella, I’m just trying to say if a problem comes to dots, it’s a dots problem, even though it’s our problem as individuals eventually because we need to deal with the problem.

To some extent, we can do our job in the time that we are meant to do it and then go home and try to have our lives. I think that’s projecting how we are envisioning our relationship as individuals with our practice, and I think dots help us to protect ourselves. That’s very useful, but it also helps us to maybe create some distance as well and just on a very basic level gives us agency to have a weekend to spend time with family, to travel home if we want to without the risk of losing all the connections. I feel that imagining that world when we decided to do this was very encouraging.

Kimie: I would also say specifically as freelancers we were always at the mercy of payments scheduled by the theaters. That was another thing which was really hard, because sometimes when you’re not on payroll, our paychecks get forgotten, even if no one’s doing it out of malice, of course. So what we’ve been doing is, any project we touch — even if I didn’t really do anything for something that Santi and Andrew are doing — all of our fees go into one bank account, and we take a salary from that. That was another specific way of trying to have more control over our financial situation as well.

Pier Carlo: Do you miss seeing your name in the credits?

Andrew: I don’t. I think for me the separation of personal identity and creative output is great. When your work is your name, then it’s hard to separate your sense of self from your work output, and I think that that’s a little unhealthy. It just puts this crippling pressure on the work, and then it makes it difficult to do good work, is what I was finding for sure. So not having my name be tied to the work, I think, is actually way bigger.

Then there’s also the added benefit that we’re building something that’s larger than any of the three of us independently, which is exciting and just feels like a nicer way to approach things.

Pier Carlo: I realize I didn’t ask maybe the most obvious question: What does the name dots signify?

Kimie: Well, there could be more! [She laughs.]

Pier Carlo: Oh, so dots is an ellipsis.

Santiago: We were spending time upstate and just thinking and brainstorming about what the essence of the company was, and we basically ended up getting little tattoos of little dots. I don’t remember if that was before or after we got the idea. What we ended up saying is dots is something that we can always add more dots to, and we always said you need a lot of dots to create a line and to connect the dots. Also more dots give more detail. I think that dots mean the essence of collectiveness, if that makes sense.

Andrew: Yeah, and the value of a whole being more than the sum of the parts, which is a thing that we care about a lot. It’s in our in company bio. That’s a kind of North Star guiding principle that we come back to a lot.

Pier Carlo: I love that you talked about the formation of the company being in a moment of great stillness and time for reflection. One thing I’ve often heard from freelance designers is that they’re so booked solid project-to-project that the one thing they don’t have time for is creative imagining. I wonder if the three of you in this collective have built in time for creative imagining.

Santiago: I think so.

Andrew: It’s a good question. I think it depends. I definitely think that the noticeable difference that I find is that when I was working freelance by myself … you have to produce so much work at such an alarming rate to try to just keep up and pay the rent or whatever that you, A) end up taking on work that maybe isn’t something that you really care about because you need to and B) end up dipping into the same old bag of tricks because you know it and you have already drafted that window or whatever so you don’t have to do it again. That just felt like that was a little creatively stifling.

I think now that we have the support and the time and the resources, I have found myself not doing that. So I don’t know if there’s built-in time for imagining, but I do feel like imagining is possible. I do think it’s reflected in our work. Looking back at the last three or four projects we’ve done, they’re all so vastly different from each other. That’s really exciting because I think a thing all three of us believe about good theater design is that each production is this unique set of circumstances to discover and that it feels a little sad to just apply the same recipe over and over again. So that’s been really great for me.

Kimie: I’m not really sure if we have more time necessarily, but being in the studio together, just having more voices that we trust, looking at something together, that just expands your ideas.

Andrew: Totally.

Kimie: Comparing my life pre-pandemic before dots, I was just working all the time, and now I do have, “Oh, I’m going to take that day off.” It still feels like a lot, but I think there has been more time to also not imagine too [she laughs], just, “I’m going to watch TV for a little bit.” And that space, I think, is necessary for creation.

Andrew: Totally.

Santiago: Yeah, and also the capacity to have a conversation about anything. If you’re alone and you need to make decisions and you’re kind of blocked, then you’re alone. I feel, for me, our WhatsApp group is such a great space for like, “Hey, guys, what do you think about this? Look at that.” I’m literally always going to be able to have feedback from someone that I trust and is in certain extent connected with the project, and that feels very privileged, to be honest. That could be for something very creative but also something very practical, like our business model.

I think that having that space for conversation, just putting out your ideas with no judgment and somebody will receive it and someone will give you feedback, that feels very good. I feel very lucky. And sometimes just to say, “Oh yeah, that was a bad idea.” It’s very easy to do it that way; somebody’s just like, “Maybe there’s another version.” Because otherwise if you’re alone, then you can end up spiraling with that bad idea for days.

Andrew: Right, and because we’re working together, we’re all on the same team here. There’s none of the weird caginess of sharing an idea with another designer and then being like, “Oh, don’t take my idea,” or whatever, which is a thing that’s part of the toxicity that Kimie mentioned earlier. I think it’s just so nice to avoid that.

Skills-wise too, we all come with very specific skills. By pooling those things and learning them from each other, we’re all growing as individuals and we’re growing a thing together, which is so much better than having to slog it through on your own and having this sense that you can’t share that stuff with other people, which is kind of stupid.

Pier Carlo: Could you talk about a recent project and how you discussed it and then apportioned the work?

Kimie: Well, what’s happening now with “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” is a very good one. That went up at BAM first, and it was a very tight timeline. From the moment we got the call to when it had to be finished, it was only about five weeks, so it was all hands on deck. I remember that I had a relationship with Annie, the director, but from the beginning we all had our initial, “Oh, hey, we’re doing this,” conversation together, and then Santi and I developed a very first model together. I think I made a very shitty version, which then Santi and I, we were looking at it together and we had a moment of, “Oh, we should do this steel-structure idea.” And we did that together.

Then I had to leave for something, I don’t remember. Then Santi and Andrew took that initial concept and fleshed that out beautifully. But the meetings, all three of us were really together in it. Then from there, once the concept was set, we divvied up the paperwork because there had to be a prop list, there had to be drafting to be done, there had to be just more model work. Then of course conversations with the director too.

So that happened all quite organically. Andrew took the lead on the drafting, but there was a day where all three of us were in the studio and took Andrew’s drafting, but we worked on all of the details and elevations together.

Santiago: And then tech.

Kimie: Yeah, and then tech.

Pier Carlo: All three of you were at tech or could you alternate?

Andrew: No, no, all three of us needed to be at tech.

Santiago: But I think we did something very smart with that tech which taught us something. Tech is a full week where you end up going back home at midnight, and we were able to, maybe, “Tomorrow you take the night off and I stay here, and then if you take the night off, you can be here early for notes.” So it’s this capacity of being present for every single step of the process but also maybe taking a night off, maybe going and having dinner with your friends or maybe just going home and sleep.

Kimie: And because all three of us were part of the conversation from the beginning, the director really trusted all of us. It wasn’t as if suddenly the lead person left and the director felt abandoned. That didn’t happen. It was all very much streamlined very thoroughly.

Pier Carlo: Because if there’s an emergency, it’s usually the assistant that then has to take the notes, and there’s not quite the same level of trust, right?

Kimie: Yes. And I had to leave at first preview to go to another tech, so then Santi and Andrew really took care of the show the rest of the way through previews. That was a great way of combining forces.

Pier Carlo: You just talked about how in your business model you’re there for each other, let’s say if there’s a family emergency, which could be ruinous for a solo freelance designer. It seems like such an obvious model to me, and so I’m surprised that there’s not more like it. Why do you think that is?

Kimie: I think what Santi said is so true. Having had that time to come together and discuss was so necessary because making a company, creating this model, it did take time. Going to our accountant, talking to other people who had small businesses, figuring out taxes, just the nitty-gritty business stuff we had to all learn, that took time.

Also part of it is I think you have to zoom out of equality a little bit, which seems counterintuitive. There’s no way that all the workload is equal, but you just have to trust each other that we’re all doing our best. I think that sort of trust and understanding of each other just takes time to develop.

Pier Carlo: How long did it take to develop for the three of you?

Andrew: I think we were in a fortunate position that we knew each other and we knew each other’s work. I think that kind of covered a bunch of the groundwork. I think trying to do this with anyone other than the two of you might have been more difficult because I think the previous relationship-ness of the whole situation just really made it possible, its being a reaction to a moment and a shared experience. It was just this thing where we had the time to be like, “Wow, we’re all going through this same thing, and it kind of sucks.”

Then also just realizing and, I think, taking pride and excitement in our foreignness too. This answers maybe your question of why people haven’t done this before in the USA. It’s because the theater industry on Broadway, it’s this thing that’s done commercially for profit, and even in nonprofit environments, it’s questionable. Making theater in a capitalist model makes it so that people want to do it individually so it’s your name on the poster. And then we were like, “Is that actually something that we as foreigners necessarily, or as humans, necessarily care about?” And then I think we were like, “Maybe not,” and that helped a lot.

Santiago: Yeah. I guess right now we talk about this with a lot of people in the industry who are very inspired by what we’re doing, but I understand that it’s hard to just suddenly start right now because, as you were all saying, this needs time. Right now it feels crazy to do what we did back in 2020: “OK, we need to sit down, create a website, the branding, write and understand what are the values and all the ideas of the company.” I feel like the free time when that happened was extremely useful and unique for the equation that allowed us to do it.

Pier Carlo: That seems like a crucial lesson to anyone who might want to do a model like yours, that you cannot form this on the side. You would need to take time off together to make that particular sausage.

Kimie: Yes.

Andrew: Yeah. There was a lot of learning about what a corporation is and that kind of thing, which was also great. It was also really nice to switch off designer-brain and switch on entrepreneur-brain for a little while.

Kimie: I also think there’s some baggage with talking about money and personal finances, and you just have to be open about that. Yeah, it’s kind of like a marriage. [She laughs.] We have a joint bank account, basically.

"Dark Disabled Stories" by Ryan J. Haddad at the Public Theater, directed by Jordan Fein, scenic and costume design by dots

Pier Carlo: We talked about “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window” and how logistically you made it all happen. I wonder if at least one of you can talk about hitting an artistic roadblock in a design and how you would not have gotten through it without the help of your partners.

Andrew: I have a very good example. I don’t know if you all are thinking the same thing: our show that we just did at the Public Theater with The Bushwick Starr, “Dark Disabled Stories,” which was an amazing show and an incredible success and work that we’re very proud of. We were in this place in December where we thought that we had the design pretty ironed out. At that point I was running the drafting and was dealing with the shops, and it was on my plate, even though it was definitely an all-three-of-us collaborative design, and we had a really good relationship with the director.

I was going back home to South Africa, and the day before, the director called and was like, “I don’t know about this whole design idea,” [the three of them chuckle] which was very valid, and I think was also a good choice in the long run. But we were like, “Well, the shops are about to build this, and we don’t know what else to do.” And the shop had also bought all this material to execute the previous idea. So we were like, “Wow, OK, sure, we can definitely rethink, but I personally can’t be in that conversation because I’m going to be a million miles away. And we also have to use all of this weird, very specific pink Spandex that we’ve got now.” And then I think it was —

Pier Carlo: You have to use... I didn’t hear that. You have to use what?

Andrew: It was just tons of pink Spandex.

Pier Carlo: [Laughing] Oh, it was! I thought I’d misheard.

Andrew: Oh no, you didn’t.

Pier Carlo: Fantastic. All right.

Andrew: And then the two of you really stepped in and saved the day and then after long discussions with the director figured out what the design wanted to be. And that is ultimately what ended up on stage and was super gorge.

Pier Carlo: Wow, so almost overnight redesign?

Kimie: Yeah.

Andrew: Yeah. And it was a pretty big change.

Santiago: It was a big change, yeah. I remember that meeting the day after you went back home. It was Jordan the director, Kimie and me in a Zoom call, trying to, “OK, now what?” I think we developed a solution that we were very happy with, but we were in the meeting, knowing, “Let’s find this together. OK, sure, we need to change this idea, but also we need to use this material because the shop already spent a big chunk of the budget on that.” That’s when the director, Jordan Fein — we love Jordan Fein — jumped into our brainstorming world, and we together found the solution.

That felt very like, “Oh, well this is collaboration. We have this situation; let’s address it together.” I feel that that would be a situation that, let’s say if Andrew or another person was designing that alone and had to go home and then that happened, that would be a meltdown.

Andrew: It’s just so lovely to know that there’s two people that you trust implicitly to do the work and pick it up. I know that whatever the solution is going to be, it will be amazing regardless of whether I’m there or not, whereas I don’t think a designer that works with assistants or whatever would feel the same way.

Kimie: Yeah. I just wanted to say that you two really saved the day … remember that time when I had to not work for a month?

Santiago: Mm-hm.

Andrew: Yeah.

Kimie: That was last May. There was just some, I’ll just call it family emergency, and I really had to drop everything, what I was doing, and put my attention somewhere else. At the time we had a pretty big commercial going with these miniatures. Then we also had to start design for this opera, which I was going to be the lead of, but it was very clear that I just could not do that anymore.

So then I called the director, and I explained the whole thing. She was very understanding. And for her too, she didn’t have to start looking for another set designer. I was able to say, “Santi and Andrew can take over this. Is that OK?” Of course, it worked out really well, and it saved the day.

Pier Carlo: And you were able to keep working and get a paycheck, whereas if you’d been working solo, you might’ve lost the job.

Kimie: That’s so true.

Santiago: Sometimes it’s the job and the money, but sometimes it’s just the emotional capacity and emotional energy that it takes. It just feels supportive; feeling the support of two other people is priceless. It just feels that we are allowed to have crisis.

Pier Carlo: Given the many institutions with which you’ve worked — in commercials, theater and film — do you have thoughts about what could be changed or reinvented at any level so that someone following in your footsteps could more easily form the kind of partnership that you have? Or even what could make it easier for you to keep doing what you’re doing going forward?

Kimie: I think transparency is really key. I think even from getting an initial offer from a theater or anywhere else, there is this lack of transparency about, I would say, money and even dates. It’s all because we’re supposed to be excited about the work. Because we somehow love our job, that seems like a form of compensation, but it’s not. It really isn’t. I think the easiest way to start is just even asking your fellow collaborators how much they’re getting paid, what is happening there, and having more conversation about it. That’s, I think, a very first step for me.

Andrew: Yeah, I think also just the acknowledgement that art is work and that artists are workers, which I think is a thing that we all believe in pretty strongly and is a thing that I think sometimes gets taken for granted. Yes, we are workers who love our job and are passionate about it, but at the end of the day, it’s still labor.

Santiago: I was thinking about when you recently graduated from grad school and you started getting offers, exposure was part of the thing. And you were like, “Wow.” I know there are memes about it, like, “I’m not going to pay rent with exposure.”

And I think, going back to the agency thing, it’s for us the agency of being able to really think about what we want to do and what we don’t need to do. Of course, we still get that sometimes wrong and we just overwork, whatever, but I guess just knowing that we can discuss that with someone, and we can navigate that together feels very powerful.

Pier Carlo: I know that clearly you have strong relationships with directors and directors get what you’re doing. Have you gotten any resistance from institutions?

Kimie: I think both. Actually, institutions don’t really mind because they want to make sure they get the product. Actually, they kind of like that for one fee they’re getting a whole team.

But for directors, I think — not recently but when we first started — there were a couple of folks were very worried about the whole idea.

Andrew: I think that the directors that we were getting some pushback from also tended to be younger. I think it was directors that were more nervous about working outside of the established system for their own —

Pier Carlo: Because there was more on the line for them maybe.

Andrew: Yeah, and I think also we’re acutely aware of the fact that directors have a lot on their plate. They have a lot of responsibility for steering the ship of productions for big institutions, and I think for emerging directors, it’s a little scary to rock the boat. That was just the sense that I was getting, which was also totally understandable, because they’re also just trying to establish themselves.

Kimie: I think they probably got worried. In their mind maybe they went to the normal designer/assistant relationship, where they were maybe worried that whoever the main person was would disappear one day and he’ll have to start over again, which I understand. A lot of designers, I think, do do that.

Andrew: Yeah.

Pier Carlo: Right. They take off to work on their next project while tech is finishing up on the current project.

Kimie: Yeah.

Pier Carlo: I wonder if you could talk about any upcoming projects that you’re particularly excited about after “The Sign in Sidney Brustein’s Window.” And that you can share.

Andrew: We have a bunch of exciting things coming up that we’re not allowed to share, but they’re exciting and we’re excited about it.

We separately all had good relationships with Clubbed Thumb, the theater company here in New York City. I think they’ve also been doing some soul-searching about how to run their SUMMERWORKS Festival in a way that just feels more sustainable for them. I think last year the festival reached a scale for them that was a little bit big for what the festival is and outside of the bounds of what they want the ethos of the festival to be, so they’ve hired us to design all three productions, which is really exciting.

I think that’s really helpful for us. We’re not doing a rep design for each show, but I think it’s just really helpful that we know what the design is for each show and can figure out what can be reused, what can be repurposed, just ways in which we can save them a lot of money.

Then we’re also folding into that equation a sustainable approach to theater-making, which is something they’re very interested in and I think we try to be. I think that’s an exciting thing. On a micro example of how this works, OK, maybe separately all three productions, I think, are going to have carpeted floors, and we’re like, “OK, great, instead of ordering three carpets three times, we can place one order and have a truck drive one time and pay one delivery fee.” It feels like a smarter way to achieve that.

It also keeps the art of it all at the foreground but also just balances the logistics and the planning. I think the success of it remains to be seen, but we’re feeling really good about it and I think the directors are too.

Pier Carlo: I love that you have tons of projects you can’t share. That makes it really fancy and exciting. [He laughs.] Congratulations!

Andrew: Not tons. [They all laugh.] Sorry. I always forget to preface the fact that South Africans —

Santiago: Exaggerations.

Andrew: We’re just prone to exaggerating a lot.

Pier Carlo: You have several, and that’s good enough.

Andrew: We have some, yeah, yeah.

Andrew Moerdyk Bio

Andrew Moerdyk (he/him/his) is a South African scenic designer based in Brooklyn,

New York. He holds an M.Arch (prof) from the University of Cape Town and an MFA from

New York University's Tisch school of the Arts.

Santiago Orjuela-Laverde Bio

Santiago Orjuela-Laverde is a Colombian entrepreneur and NYC-based film and set designer.

Co-Founder of Dots Design Corp in NYC. MFA @ NYU Tisch. Santiago is also the Co-Founder

and former Creative Director of the fashion and retail brand KUPA.co based in Colombia

- FORBES 30 under 30 - Best 30 Entrepreneurship in Colombia 2020. Tattoo artist enthusiast

and passionate reggeaton historian. Self-proclaimed professional playlistster, and

his favorite fruits are mango and watermelon.

Kimie Nishikawa Bio

Kimie Nishikawa is a scenic designer from Tokyo, Japan. She immediately moved to the

United States with her family at the age of two, moving around the east coast and

growing up there until the age of 10. After graduating from Sophia University (Tokyo,

Japan) with a degree in The English Language, she pursued a career in theater that

first started out as an after-school activity in college. She enjoys making miniatures.

MFA NYU Tisch School of the Arts.

April 24, 2023