Funding the Invisible: Esther Hernandez on Artists’ Labor

Listen to the interview on Apple, Spotify, or your listening platform of choice. Captioned interviews are available on YouTube.

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

In June of 2025, multidisciplinary artist Esther Hernandez posted two videos on Instagram that she herself described as rants, though she was fully composed through each. In each video she called out arts institutions and funders for expecting artists to provide evermore work gratis. As she herself put it, “I am tired of watching artists be expected to carry so much to make socially engaged work, to give back, to support the community, to hold the weight of healing or justice when most of us aren’t even resourced to pay our bills, let alone afford health care or rest.” She also lamented that nonprofits were, in a time of admittedly frightening fiscal precarity, leaning on underfunded artists for financial support.

Esther clearly hit a nerve with artists everywhere, and her rants amassed thousands of views and messages of commiseration and support. She can also rant with some authority because not only is she an artist, but she has also worked in the arts nonprofits sector. A self-taught maker of stop-motion animation and movable or mechanized sculptures and zoetropes, she is currently Chief Curator at Union Hall, a six-year-old nonprofit in Denver, CO, that provides support and professional development to emerging artists as well as curators.

In this interview, Esther reflects on the inequities that drove her to speak out and on how her posts sparked broader conversations about the invisible labor of artists. She also shares how her dual perspective as both artist and curator informs her ideas for more sustainable funding models and healthier creative practices.

Pier Carlo Talenti: I want to talk about the mood you were in when you recorded the rants because in the first you said you’d been sitting with something deeply and you were holding a lot of tension. Was there an inciting event that made you want to record these videos?

Esther Hernandez: Yes and no. Honestly, I was diagnosed with a chronic illness in the summer of 2024, and since then, my capacity ebbs and flows. And I also know that I’m not the only one. That particular day when I posted, a friend and I had a conversation about something she was going through. I can’t share her story obviously, but it made me really upset just to hear how she was being taken advantage of. And on top of that, on the same day, I think I got an email from a nonprofit leader asking artists to give them money — artists that they had supported — and it just really rubbed me the wrong way.

I think the accumulation of my struggles in 2024 and what I had been going through and just having a sense of burnout and exhaustion from the project-to-project-based contractor model and then seeing nonprofits scramble to make ends meet by leaning even more heavily on artists just really triggered me and upset me. That’s not a normal thing that I do. I don’t make posts like that. And honestly, I was shocked by the amount of support and how far of a reach those posts got.

Pier Carlo: How are you feeling now, having posted them and having received that support from fellow artists?

Esther: Oh, my gosh, I think it’s really telling how much artists really resonate with what I posted and with the struggle. And I also felt relieved, like, “Oh, my gosh, I’m not the only one.” Obviously.

Some people stated that being an artist and being in the art world is like dealing with an emotionally abusive partner, and I can relate to that. I feel like the hustle was perpetuating the conditions of my own personal childhood trauma of always needing to perform to prove that I’m worthy of these little bits of validation.

I’m feeling a lot better. I’m feeling a lot more free. I’m feeling like I can lean into these conversations because they’re important.

Pier Carlo: Your story reminds me of … I used to work for a large theater company on the West Coast — this is long before the pandemic — and there was a big staff meeting where the head of development decided that she would try to convince us to join a monthly donation group to support the theater. We were barely making rent. But the idea that your staff, who are being massively underpaid, should be expected to also support the institution in which they work, this idea that anything goes in the race to raise money, was just astonishing.

Esther: Yeah. I think right now in particular it’s just that nonprofits are having a really hard time because a lot of federal funding got pulled, and because the federal funding is getting pulled and renegotiated, a lot of local and state funding is also affected, so there’s a trickle-down effect. It’s a real struggle for nonprofits right now, and I totally understand that, “Hey, let’s just get funding from wherever we can,” but I just don’t think it’s fair. I think a lot of people that are doing that don’t realize what they’re doing or how it’s affecting the creative community.

Pier Carlo: Speaking of more demands placed on artists, one of the things that you bring up in one of your videos is something that I’ve often thought about, namely that in order to get funding, an artist has to prove that not only is she making her art but she’s also giving back to her community, whether through education or any kind of events or in a demonstrable, tangible way. So the idea is that artmaking alone is not worthy of support, that there has to be added value put onto it, which drives me crazy. How do you think this could be remedied? How could donors get the message that it is unfair to ask more of artists?

Esther: This is a tough one, and this is a really big piece of what I struggle with, being on both sides of the fence. I think the problem really comes from the idea that funders treat artists like part-time social workers. They want this measurable community impact on top of the art itself, but it’s for a stipend that doesn’t even cover living costs. There’s not really any other professions that are asked to operate like that. Well, except maybe teachers.

I think the remedy is tough. I don’t know if I have the answer to that question. But I do think that funders sometimes might need to be educated and that they should trust artists more and potentially fund art directly with no strings attached and stop assuming that art only has value if it can be measured in community metrics. Because the art is the impact in my opinion.

But there’s other things that we can do. I think we need more working artists on boards, especially in nonprofit spaces. And educated funders could start valuing unrestricted grants. They could start valuing living-wage stipends. They could start funding process-based things like research, rehearsal, exploration, because a lot of that is invisible labor that doesn’t get paid. We don’t get paid for that invisible labor.

Pier Carlo: Right. So in a proposal for funding, for instance, an artist would talk about the full scope of her work, starting with ideation through research, development, to the actual making, and the funder would then be encouraged to fund the whole process?

Esther: Why not? That’s ultimately what we’re doing as artists, and what’s being valued is only the end result.

Pier Carlo: It’s interesting that you mentioned that the only other profession that is expected to do a lot of invisible labor for free is teachers. I have a sense that, like teachers, artists are expected to pick up a lot of the cultural education slack that’s being taken out of our public school system.

Esther: It’s so true. Oh, my gosh. It’s a sad reality that nonprofits are the ones stepping in and bringing artists into Title I school districts so that they can have an arts education. I think that that is very important work that nonprofits and artists are doing, but it’s just a sad reality that that’s where we’re at right now.

Pier Carlo: I know Union Hall, as you told me, does pay artists respectfully for the time they share if they’re asked to do anything beyond their artmaking. How did that ethos become part of Union Hall’s functioning?

Esther: I’ve only been at Union Hall for three years. [Laughing] I told myself before I got the job that I was not going to work in another nonprofit art space, but then I was an artist in an exhibition at Union Hall, and I was so impressed with the space and with the staff, and I remember leaving, thinking, “Oh, this would be a cool place to work.”

At the time, we had an executive director named Emma Steuer, who was responsible for really creating a lot of those values in conjunction with Ari Myers, who was the previous chief curator there. Working together, they both set a lot of precedents for how they want to treat artists and the values that need to be upheld to really create an equitable and sustainable ecosystem. The only reason why I took the job was because I thought, “Wow, I could really stand behind what’s going on here.”

Pier Carlo: Because you’d experienced it as an artist.

Esther: Mm-hmm.

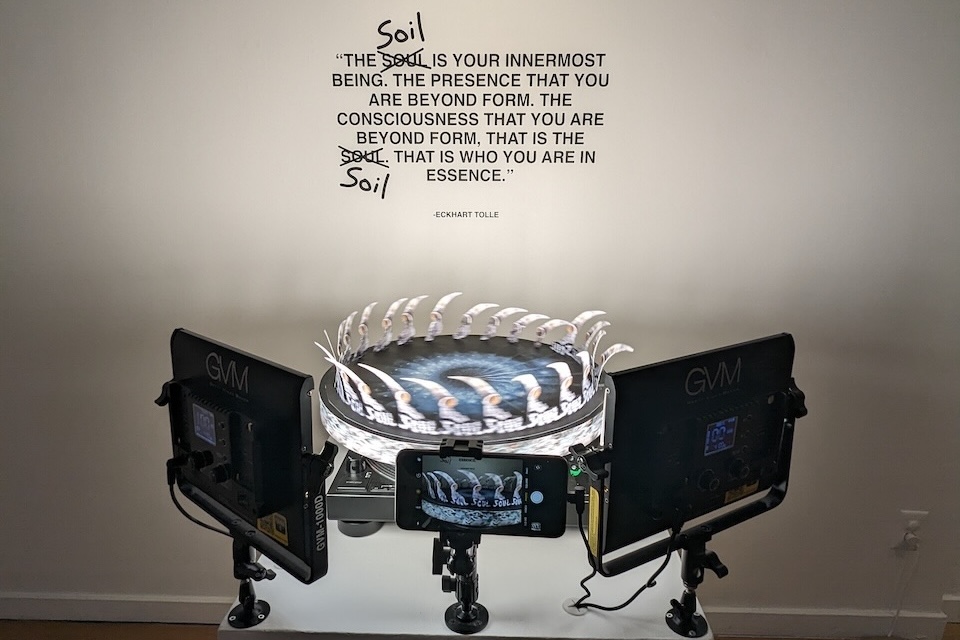

“Soil as Soul,” Esther Hernandez, agriCULTURE: Art Inspired by the Land, June 8 - October 1, 2023, Boulder Museum of Contemporary Art; Photo by Gina Pugliese

Pier Carlo: One of my later questions for you was, “Was there an instance in your career when you felt well-supported in your artistic endeavors?” And this sounds like one of them. I wonder if you can talk about how you were supported by Union Hall and for that one event in a way that most nonprofits, you feel, do not support artists. What were the highlights of how you felt taken care of?

Esther: Honestly, it was a very small show. I just had a short video piece in the exhibition. I’m used to doing all of my installation myself and having to figure all of that out, but that wasn’t the case. I literally just sent them a file, and they did the rest. Every space is different, every staff has a different capacity, but it was just really smooth.

In terms of receiving support as an artist, the most I’ve probably ever felt supported in my practice was when I had a two-year residency at RedLine, which is a nonprofit art space in Denver. They give you a free studio for two years in a community setting where you meet other artists, you talk about best practices and industry standards and you really learn a lot about professional practice. I think that space for me was when I really started to understand what was required of me as an artist in terms of my professional practice in order to really move forward.

Pier Carlo: Could you give me an example? Because I’m not sure I understand what you mean by learning about professional practice.

Esther: Oh, yeah. It was an open studio, so curators would come in and talk to you; people from the community would come in and talk to you; and you had to get used to talking about your work and how you do it and what it is. Up until that point, I don’t think I had experienced that level of engagement with the community around my work, so it forced me to up my game and to get business cards and have a website and understand how to write about my work. I was also asked to be in a lot of different exhibitions at the time that were also paid opportunities, and that really helped me understand how to write about the work and what expected of me in general.

Pier Carlo: That’s amazing. Is RedLine still operating?

Esther: Oh, yeah. I’m sure there’s other residencies like this in the country, but I just haven’t heard of many of them.

Pier Carlo: Because those are some very useful tools to put in any artist’s toolbox.

Esther: Oh, yeah, absolutely.

Pier Carlo: We talked about convincing funders to support the whole breadth of an artist’s imagination and artmaking. How do you think the average American could be convinced to understand that artmaking is labor in of itself, that it’s not just a hobby?

Esther: That’s a challenge. Going back to what I was talking about earlier, because of the stereotypes and the tropes that exist within capitalism, I feel like that’s a big hurdle. Anytime I’m out in the world and people are like, “Oh, what do you do?” and I tell them I’m an artist, I feel like they just think, “Oh, how lucky you are to get to just make art all day.” Like I have the easiest life in the world.

But honestly, artists are some of the hardest-working, most resilient people that I know. They not only sometimes work full-time jobs and then have a thriving practice on the side and have families, but they are also cultural workers and caretakers, and they’re shaping identities and they’re offering visions of future possibility. They’re juggling all of these different things, and I don’t think that the general public realizes how much it takes to carry all of that.

Pier Carlo: Well, it feels like something like what RedLine was doing, which is encouraging the community to come in and talk to you and see you work, is one possible avenue.

Esther: Absolutely. Inviting more conversation and engagement is absolutely a remedy. I think documentaries about artists and their lifestyles and what it takes are also very supportive.

Pier Carlo: How is Union Hall doing in this current climate where so much funding is getting cut? How is it doing financially these days?

Esther: Well, we’re also struggling like any other nonprofit space. I think we are a little bit different in that we are the first non-commercial nonprofit art space that exists inside of a residential building in Denver. We’re funded from a foundation associated with the building. The foundation gets money from real estate sales within the building, and so that’s a new model. I don’t think that we would’ve made it through the pandemic without that funding since we only opened in 2019.

Another unique funding model that’s specific to Colorado is the SCFD, which stands for Scientific and Cultural Facilities District. This is a unique funding model that’s funded by a 0.1% sales-and-use tax, and the money is then distributed to cultural organizations across the region. It only exists because voters chose to tax themselves in support of cultural life.

Pier Carlo: I think this happened in Minnesota too. Something similar.

Esther: Yes, there is something similar in Minnesota. These organizations that are funded are big institutions like the Denver Art Museum, the Denver Zoo, the Botanic Gardens, as well as hundreds of small and mid-sized community art spaces and cultural groups.

Pier Carlo: You brought up this interesting hybrid model in which you’re working. You’re not only an artist, but clearly you also have a lot of nonprofit leadership experience. Do you have any other ideas in your back pocket about new systems that could support artists consistently?

Esther: Yes. I don’t consider myself a nonprofit expert by any means [laughing] or someone who has that much experience, but these are things that I like to think about in terms of, how can artists have sustainable livings in ways that aren’t extractive? I don’t have a lot of the answers, but I do think that there are some things we can do, and I am interested in some of these models. What do membership cooperatives look like instead of hierarchical spaces? How can we build artist-led co-ops where members contribute dues and have a collective say in programming or resource allocation? Things like that, things like community ownership, community land trusts or shared studio spaces that retain equity.

And then I think it was San Francisco that started a universal basic income for artists, which was a pilot program where they sent them $1,000 a month. That’s amazing. I don’t know if that’s continuing or if that pilot program ended, but I think that could be a really interesting support system for artists as well. That really reduces dependence on competitive grants, gives artists more stability.

Another thing too that I think is important is holding organizations accountable by using tools like WAGE, Working Artists for the Greater Economy. And there’s another one called CARFAC, but it’s Canadian-based. I think artists can start saying no to bad opportunities and calling them out when they recognize them, holding institutions accountable to create more change and awareness around an equitable practice.

Pier Carlo: I’ve noticed that you do that sometimes.

Esther: I do. I did post it on my Instagram just so that people could see what that looks like because I don’t think that it’s a natural —

Pier Carlo: Could you talk about what that post was discussing?

Esther: There’s a well-known organization in Denver. I won’t call it out or anything, but I know that their annual budget is probably around $4.9 million a year. They had sent out a call for entries for artists to design a poster, but not just design a poster. It was to design a poster with all of these other images and ideas in mind and then to also go to a big slew of events throughout the year that were considered exposure, basically. “We’ll put you on this pedestal and tell everyone that you made this poster.” And honestly, I can’t remember what the stipend was. I think it was somewhere in the ballpark of $600. And I was appalled, to be honest. I think there was even something about merchandise, like, “We’re going to sell these posters, and you’ll get a percentage.”

It really irked me. I thought, “I can’t share this with my community. $600 is not enough to show up at all of these events to spend —”

Pier Carlo: Also it makes it so clear to me that they do not have a single artist on their board of directors, because that kind of stuff wouldn’t fly.

Esther: Yeah. And they were actually incredibly sweet and responsive.

Pier Carlo: Hey, that’s great!

Esther: I sent them an email, and I was just like, “Look, this is just perpetuating unsustainable living wages for artists, etc. You would never go to a graphic design contractor and say this to them. Ever.” I said that to them. So they changed the stipend, and they offered pay for each opportunity, up to three. They made the opportunities optional.

I think institutions sometimes do need to be educated because they’re still holding onto these very old ways of operating and thinking when it comes to hiring artists and their labor.

Pier Carlo: Especially in these times when it’s hard just keeping nonprofits and artists’ heads floating above water, how do you take care of your spirit these days, your anxiety? How do you take care of your artist self and your nonprofit business self?

Esther: Oh, that’s a really good question. Well, I’m often working multiple jobs as a contractor, and they can all be very different on the spectrum of creativity and timelines. I can get burned out if I take on too much, so I try to pace myself.

But when things are generally overwhelming and I know I still need to work in the studio or have creative time, I will actually block off days on my calendar and just say that I’m out of office and take a mini residency but at home. I will put an out-of-office on all of my emails. I’ll say no to every invite or engagement and just enjoy the solitude and the spaciousness of that.

It could be two days in a row; it could be a week. It just depends on what I need. And I will do that in advance for myself, because I’ve found that I can get so wound up in my jobs and what I’m doing that I will suddenly realize, “Oh, my God, I haven’t been creative,” or, “I haven’t taken this time to build on this project I’m working on.”

Learning how to say no, to be honest, has been a really big issue in the past, but I’m getting better at it.

Pier Carlo: I’d love to hear more about that because you brought that up early on in our talk. Talk about that process of not saying yes to every opportunity if it doesn’t align with your mission or your goals.

Esther: [Laughing] It’s hard because I historically have failed at it by just saying yes to everything. Part of that comes from a scarcity mindset in my opinion, thinking, “Oh, I need this job. Oh, I need this stipend. Oh, I need this.” And as soon as I stopped doing that, I just started to feel better in my body, to be honest, more calm. Intentionally choosing to say yes to things that really only align with me and support me has really changed the game for me. There can be moments where it feels confusing, where it seems like a really great opportunity, but it doesn’t feel good to me in my body.

Pier Carlo: In terms of determining whether it’s going to be good for you, is that where you feel it? In your body?

Esther: I do. I have a systematic practice. I’m also an energy worker, and I do a practice called somatic channeling. This has helped support me in so many ways in my life in terms of just releasing trauma from the body and tuning into what I need and helping me shift my perspective on a daily basis. That is really where a true source of support comes from for me.

Pier Carlo: And then, looking out of the next 12 months, is there a project, whether in your artmaking or your curatorial practice, that you’re particularly looking forward to?

Esther: It’s really funny because the project that I’m most looking forward to is truly free. It’s not something that I’m really getting any notoriety for or anything. It’s just a personal project. A friend of mine is an incredible musician. His name is Doo Crowder. He lives in PA. I’m making a stop-motion video for him for one of his songs, and it really just feels like a childlike pleasure that I really need in life. Sometimes that is the most impactful thing for me and others. Yeah, that’s what I’m really looking forward to.

October 08, 2025