The Floating Museum

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Architect Andrew Schachman and multidisciplinary artist and educator Faheem Majeed are two of the four artists who, along with poet avery r. young and sculptor Jeremiah Hulsebos-Spofford, co-lead Chicago’s Floating Museum. As its name suggests, the Floating Museum does not have a brick-and-mortar fixed space; rather it creates inventive projects through which to explore and strengthen the relationship between art, community, architecture and public institutions in sites throughout Chicago.

One example of past Floating Museum projects is “Cultural Transit Assembly,” which activated not only the Chicago Transit Authority’s Green Line but also parks and spaces along its track. Some Green Line CTA cars served as pop-up performance spaces and galleries, and giant movable sculptures as well as community-art events could be spied from the train throughout its route, inviting riders to visit neighborhoods that perhaps were new to them.

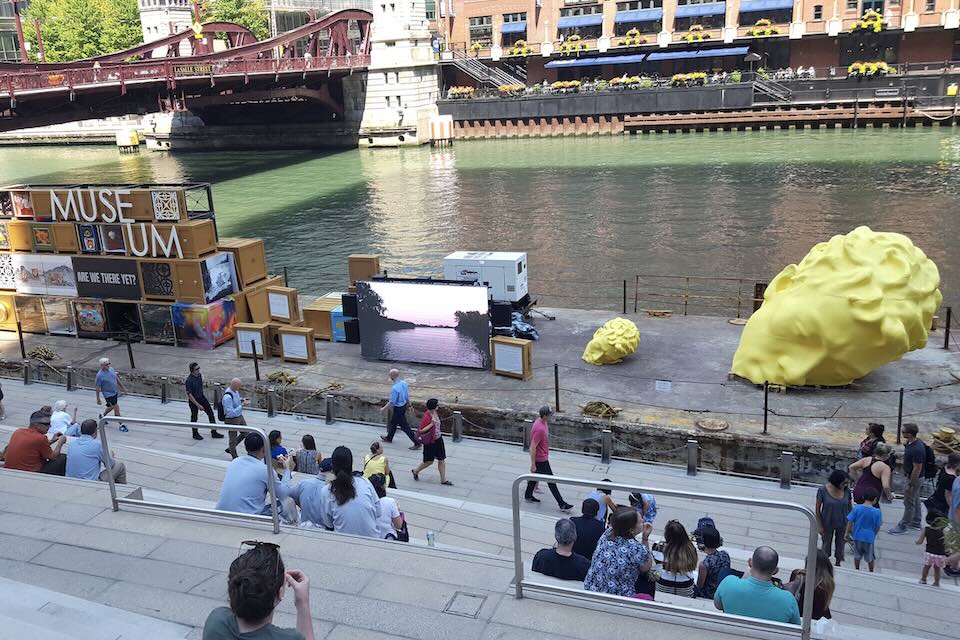

Another example is “River Assembly,” which over a month saw an industrial barge dock at different sites along the Chicago River, bringing a host of performances and interactive exhibits to several neighborhoods, celebrating the entire city as one giant museum campus, all corners of which have always been hubs of culture and art.

In a sign of the Floating Museum’s cultural influence not only citywide but also nationally and abroad, its four leaders were tapped to be the co-directors of the fifth Chicago Architecture Biennial, one of only two architecture biennials in the world, the other being the century-old Biennale in Venice, Italy.

Here Faheem and Andrew describe the municipal savvy and community trust they had to cultivate for the Floating Museum and its many projects to move throughout Chicago. They also discuss how as a quartet they manage a growing institution that must remain nimble and responsive enough to continually engage with its home city.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- Describe the first project or activation that laid the foundations of what would eventually become the Floating Museum.

- One of the things you had to do early on in the process was learn each other. How did you figure out your co-leadership style?

- Let’s say someone wanted to replicate the model of the Floating Museum in their hometown. What would you tell them that would best prepare them for this challenge?

- How do you go about ascertaining whether the community or the neighborhood in question wants this kind of creative intervention?

- How did you come up with the title of this Biennial, “This Is a Rehearsal”?

- The Floating Museum is currently going through an expansion. I’m wondering if you can say more about what that entails?

Pier Carlo Talenti: Describe the first project or activation that laid the foundations of what would eventually become the Floating Museum.

Faheem Majeed: We [Faheem and Jeremiah Hulsebos-Spofford] were going to float down the Chicago River with a model of the DuSable Museum, which is now in a big building, and float it down the river with this idea of, what happens when you move a cultural institution from its neighborhood to the kind of cultural center downtown, which is where the cultural capital is. It’s where the museum campus is. Kind of as a poetic gesture.

We went to the DuSable Museum and talked with this director at the time, and she laughed at us because we thought we were going to dumpster-dive and do this for like $20,000. She said, “You won’t get a nickel,” and she just laughed. And I said, “Why?” She said, “Because people think you’re going to hustle them.” I said, “What do you mean? $20,000, is that too much?” She said, “No, it’s too little. You cannot do this for $20,000. They know you’re not trying to do it because that’s ridiculous, so you must be up to no good.”

At the same time, Jeremiah met this amazing person who was an architect and was a friend of his, and we sat down to eat. That was Andrew. Andrew — we have a space here called the Hyde Park Art Center — was the lead designer when he worked for Garofalo Architecture. It’s a space that’s near and dear to pretty much all of Chicago. It’s near and dear because of how the building functions. It’s not precious surfaces; it actually serves. We started talking about the building, [founder of the DuSable Black History Museum] Margaret Burroughs and shifting for people. He was like, “What if the building actually literally moved?”

So that’s when Andrew stepped in really and how we met, through this initial first project that we were trying to get done. How long ago was that, Andrew?

Andrew Schachman: Wow. Yeah, that was 2015.

Pier Carlo: And how long did that take to pull together?

Andrew: Well, that took about two years partly because we realized we needed to rehearse the gesture. Partly that was about law and protocols and coordinating with a whole lot of city/municipal permit-granting organizations, coast guards, park districts. It was a lot more complicated than just the literal action because of all the organizational issues that come up when you navigate a space that’s unusual like a waterway, which has totally different legal conditions on it.

Pier Carlo: What does “rehearse the gesture” mean? How much rehearsal is involved in that gesture?

Andrew: Quite a lot. It actually was a whole separate project. We were activating in some cases parks adjacent to the river, so we already had a relationship with some of the people in the Chicago Park District, which led us to a project in Calumet Park. It was essentially a temporary structure, a scaffold that was erected with the thought that we wouldn’t waste any material, that we could rent a scaffold, and they could build a kind of framework structure in the park. It would come with a crew to assemble it and a crew to take it away.

We worked with an attorney who came on board who we joke about as kind of a quiet artist, even though he would reject that. We worked on legal documents — because they didn’t exist within the Park District — to install temporary frameworks for people to gather in the way that we were thinking about gathering and collecting and having exhibition space in the public realm.

"Translator" by Victoria Peterson, 2019, part of the Floating Museum's "Cultural Transit Assembly"

Pier Carlo: Did you all have any idea what this was going to entail?

Andrew: No, but it was interesting too, though, because our attorney at the time, a really great pro bono attorney named Steve, was writing bonds for the City of Chicago, and he already understood some of the city’s protocols. One of the things that that opened up was also leaving behind legal frameworks that other people could use after our intervention in the site. Some of those legal frameworks are still used today and have allowed more flexibility in the park space for new kinds of activations and community events to happen.

Pier Carlo: Oh, so you actually changed the city on a municipal legal level!

Andrew: In a quiet, concrete way, we did, and that underpins a lot of our practice now.

Pier Carlo: That’s amazing. Over how many days was the event, the first floating of the museum?

Andrew: Thirty.

We don’t bring culture to people; people already have culture. We’re just like, 'What if you have a 30-foot inflatable? Would you like to go down the river with us on this barge?' It’s a horizontal value set.

Pier Carlo: Thirty days. It was a month long!

Faheem: Yes, 30. But just to be clear, although we’re called the Floating Museum — this is very confusing — the point isn’t to be on water or float on air. The floating aspect is really about movement. It’s almost like museum without walls. The idea is to float around the city and now kind of around the world so that we move a set of resources, ideas, collaboration and collaborators around the city. It’s a way of not even bringing the museum to the people but understanding that the people are the museum and just supporting what’s already there.

We don’t bring culture to people; people already have culture. We’re just like, “What if you have a 30-foot inflatable? Would you like to go down the river with us on this barge?” It’s a horizontal value set. That’s why we said Calumet Park was where we first rehearsed with a standstill structure behind a Park District building so we could work out how to work together, we could work out how to work with the city, we could work out legal agreements, we could work out our curatorial style, our building style without the pressures of a strong deadline.

We learned some things, and that was a neighborhood that was closer to Indiana than it was to downtown Chicago. It’s literally the last neighborhood on the books before you go to another state. So our first two sites were literally on the west side and the south side closest to the fringe, to the edge.

The floating down the river didn’t happen for another two years after that project. We did like three projects, maybe two projects, before we actually floated because we had to learn each other first.

Andrew: And also learn to activate sites in the city in this particular way and also to understand the constraints of the city in order to think about how to adjust those constraints or push against those constraints.

You know, there was also Redmoon Theater. They had attempted to light something on fire in the Chicago River, and it rained that day and it kind of smoldered. We met with them, and in the most generous kind of artist-to-artist conversation you can possibly have, they told us about their experience trying to accomplish something that was really difficult and having it not go as expected. They told us all about the nuances of that experience. Partly because of that, we realized we needed to rehearse, to build up to something, because we didn’t want to do something so public in our first gesture and not succeed.

Pier Carlo: Faheem, you mentioned that one of the things you had to do early on in the process was learn each other. How did you figure out your co-leadership style?

Faheem: I think it was commitment to time. Early on, one of the commitments was to meet once a week for an hour. An hour doesn’t seem like much, but when you stack up almost going on close to a decade now, that’s a lot of time. And we don’t meet for just an hour. We never meet for an hour; we had a minimum.

Andrew: It always turns into five hours.

Faheem: It always turns into five. We meet way more than that because it was about being around each other. It was also just small things we learned. And I do think it is special because, although we all have our own ... . We have egos. I mean, we’re all creatives, and artists are known for their egos, but we check that at the door or we leave it in our studios and think about who needs to be up front, who makes the most sense. A lot of that’s been an intuitive type of thing that I think just from being around each other, supporting each other, has helped. And it is special. It’s unique.

I’ve seen many collectives fizzle out from the wrong chemistry or things not lasting or people not willing to back away or things like that, so we’ve just been really fortunate. Avery r. young came on during the barge project. Two years in, he comes on.

I think in a lot of ways we try to challenge space, so we did have this idea of always adding new directors. What if we had an organization that constantly was sliding to make space? And so a lot of our pavilions and our spaces —

Pier Carlo: Which, right there, is pretty revolutionary for any institution.

Faheem: Right. There’s institutional critique in all the stuff we do. And we had a lot of performers.

I had a friend that I knew named avery r. young, a big fan, and he came on and did a performance with me and the project I did at a museum, and we hosted a lot of musicians and poets. He said, “Instead of just hosting them, we should give them a space.” So I said, “Avery, will you come on as co-director?” He said, “Sure.” I don’t think he understood what he was saying at the time or what he was getting into, but next thing you know, I mean we’re literally going down the river and he has to take all this in. It was so quick, such a quick turnaround, but it took a good two years for us to learn avery and for avery to learn the rest of the group and everything else.

It was very jarring. Avery communicates very differently. He’s Chicago’s first poet laureate. He’s definitely the rock star of the group and the most fun, hands down, but also kind of the busiest in how many spaces he supports. So once again, we all have our own kind of spaces. and we come together with things. He’s kind of our sage morality in a lot of ways.

Andrew: I’d also say we all had somewhat established practices and reputations before we met each other, so our investment in Floating Museum has not been a technique to build a reputation necessarily. It has been a lot about satisfying things that I think a lot of us thought were missing in our independent practices and the constraints of those practices and then creating our own space, to take risks together to satisfy some of those critiques, I think, that we might have developed in other work.

Pier Carlo: Whereas otherwise there might’ve been more ego involved in the leadership.

Andrew: So it’s really easy for us to put our egos aside because we’re getting to realize and act on and think about things that we care about together. I would also say that we were seeing the same things from different points of view.

What holds us together as a collective from an urbanistic and architecture — I have an art background as well — point of view is seeing something from that lens is maybe different than seeing it from a performance or sculptural or administrative lens. But knowing together that we share a hallucination about things that are missing and maybe a hallucination about the way things might be allows us very easily to put our egos aside because we all have a shared mind frame, even though that might express itself slightly differently depending on our training or education or our life experience.

Pier Carlo: Let’s say someone wanted to replicate the model of the Floating Museum in their hometown. What would you tell them that would best prepare them for this challenge?

Faheem: Hm. It’s about a process. What I always say is that we use spectacle as a way of galvanizing expertise. Like, we can’t float a barge down the Chicago river without the ferryman, the tugboat captain. We put these things together to go into neighborhoods where they’re just not going to work if there’s not a certain amount of buy-in. So we don’t work with the communities; we work with the people who work in the communities. You understand? That are already there. It just strengthens the workers and invests or gives them resources in a way that benefits the spaces that they care about. That way it stays. I think it’s about the process.

Pier Carlo: How do you go about ascertaining whether the community or the neighborhood in question wants this kind of creative intervention?

Faheem: We ask. We ask a person. The community is infinite. On one given block, there could be ... . Community is a very nebulous word. There are a number of communities on my block, there’s an ecosystem, and all I’m saying is work with one of those people on that ecosystem. It doesn’t mean you’re going to solve. It’s not about solving anything. It’s not about fixing anything. It’s just about highlighting something that may be there. An offering.

Miss Jenkins, that’s been doing the community block party for 15 years out of her pocket, you go to Miss Jenkins and say, “Hey, Miss Jenkins, would you like a 30-foot inflatable monument and some docents?” “Oh, that’d be great. How much that cost?” “Well, that’s free for you because that satisfies our mission.” Or she may say, “That’s a big distraction.” I’ll say, “Well, can we just come?” “OK, you can come and sit down and eat.” Once again, not forcing things onto people, but having a dialogue conversation. Each one’s unique. Many of our projects are representations of processes of different lead artists, different community stakeholders, and they just take different forms.

And as Andrew said, we switch directions. We’ll throw the whole project out if it doesn’t make sense.

Andrew: Yeah, like you’re saying, the process is part of the art. I would also say spending time and developing real relationships is part of the art. Without those real relationships, there isn’t ... . People say this often in Chicago, but things happen at the speed of trust. Without spending time and developing real relationships, that trust doesn’t happen.

Pier Carlo: How did you come up with the title of this Biennial, “This Is a Rehearsal”? It makes sense, given the Floating Museum’s ethos, but how did you picture it in the Biennial setting?

Andrew: We would always say our prior project is a rehearsal for the next project, so I think that’s already part of our ethos. But architects around the world … . That’s one thing that a biennial does; it sounds incredible to say, “Architects around the world.” A biennial lets you speak to architects around the world. That platform opens those conversations up.

The advantage of having those conversations is, I think, we learned that architects are recoiling a little bit from the 20th century manifesto after manifesto after manifesto proclaiming solutions and answers to social and cultural and other problems, technical problems. I think a lot of architects have doubt about what those manifestos produced. I mean, a lot of them produced things that seem contradictory to the agenda. The outcome often is contradictory to the ideology.

I think we’re having a moment on Planet Earth because of a lot of different pressures — climatic, political, ecological — where we’re starting to wonder whether our systems are producing the effects that we expected them to. I think a lot of architects were really open to thinking about structural questions and also having the opportunity outside of the confines of practice-for-profit to realize something that they’ve always had bouncing around in discussion and actually having a chance to rehearse that and maybe put that out into the world. Because putting it out into the world makes it real enough for someone to say, maybe a client to say, “Can we continue to act on that and think about that idea that you have?”

I think a lot of people were excited to hallucinate together through that framework.

Pier Carlo: One way to talk about what happened at the Biennale is for each of you to share a moment of creative hallucination that really spoke to you.

Andrew: A few things. One of the things that we decided to do curatorially is mix institution, municipal authority, individual practice, small practice, large practice, sometimes soliciting collaborations between entities. For example, Columbia University’s Buell Center, who researches the American landscape, collaborated with architects and researchers to put together both an installation that relates to the way the American landscape was structured as a capital medium in a certain way with an installation and a text. It’s a kind of all-encompassing environment and academic resource in the cultural center. It’s not just how we organize the land but how the idea of land even emerges in the United States and what its nuances are as opposed to the idea of land elsewhere. The production of the idea of land is what that installation is really about, I would say.

And it echoes with other installations in the exhibition. We have an installation from Ruth De Jong, who works with Jordan Peele and Monkeypaw, which is related but through a whole different medium of cinema, specifically horror. In a way, they’re thinking about parallel subject matter but through different disciplinary points of view.

Faheem: For me, it’s so hard to choose. We had 80-plus architects and artists. They all could hold down the spaces themselves.

I think one of the things that excited us in the beginning is we thought this would be the opportunity to activate the whole city. We quickly learned that we actually do have very big appetites and networks. All the sites pretty much that we chose were sites that we previously had relationships with, that we had done projects with, that we understood their missions, we understood that their timing was different than, say, an exhibition and their relationship to urban infrastructure or culture timing. And we were able to communicate that and make partnerships that were beneficial. Once again, how do they eat? What do they really benefit from?

Our worst fear was plopping something into a community or a space that we see as a friend and then them having to carry the burden. Now, some of that’s inevitable when you’re doing something really big. But what we eventually did, and just came to a moment once again in “This Is a Rehearsal,” was to challenge the notion of biennial.

Andrew: In some ways we were thinking about the Biennial as a relational framework, so municipal authorities, institutions, individuals, could collaborate together in new ways. And also thinking about, for example, some biennials will, say, build a pavilion, and then the year it’s closed, suddenly there’s a pavilion that people have to maintain and program, and it becomes a burden as opposed to a benefit.

"River Assembly" 2017; Photo courtesy of the Floating Museum

Pier Carlo: Right, that’s kind of like the World’s Fair model.

Andrew: Yeah. We already have a practice in Chicago with, as Faheem said earlier, working with people who work with different constituencies in the city, so rather than site something in a kind of unmanaged space, we could invite organizations around the city of Chicago who maybe wanted some design services for something they really needed to realize and then figure out how to use some of that Biennial money to also help seed that project.

So for example, Urban Growers Collective is a farm on the South Side of Chicago. It has actually seven sites, but the site that we invested in is near Steelworkers Park on the South Side of Chicago. Southeast. We paired up with a firm from New York who thinks also about building at a different timescale, building as a kind of slow, evolving almost growth. Because Urban Growers Collective is a farm-based art-and-community support and research framework — that’s their practice — they’re a really good partner. They also happen to both be members of the Mycelium Society, thinking about mushrooms from different points of view. So the farm group would think about mushrooms as medicinal and nutritious, as a plant, think about its ecology, and The Living, who’s the firm that from New York that we paired them up with, thinks about mycelium production as potentially a building material.

So that’s a slow research project that gets kicked off with the Biennial. There’s a pavilion now up, but the timings of that are not necessarily on Biennial time. They start with Biennial time, but they can continue to unfold for a decade, also because Urban Growers Collective is there to maintain and program and think and use and evolve that pavilion. So it’s a little different than, like you say, the World’s Fair model. In some ways that’s about the deep structures of biennial form, thinking about its nuances and thinking about how to maybe misuse or subvert biennial structure.

Pier Carlo: Faheem, you said that Floating Museum is currently going through an expansion. I’m wondering if you can say more about what that entails.

Faheem: I think we are moving from a passion project in a lot of ways to growing up, to formalizing some things. I won’t even say that; that’s putting a cart before the horse. Really figuring out what we want to be, where we want to go, and what each of our roles is in that, just thinking about how we want to evolve and grow. Understanding that, you know, when you make a good cookie, eventually Betty Crocker comes looking for you. And we’ve been making good cookies for a while. Thinking about it’s no longer a passion project. We’re bringing on permanent full-time staff.

Pier Carlo: Is that disappointing?

Faheem: No, it’s just something to think about, take seriously. It’s not something we want to be knee-jerk about. I’ve done that already. I’ve been through that with the last organization. I’ve seen it happen in many ways. We’re taking that seriously, but it’s exciting because now we’re going to have residencies. We’re looking at fabrication facilities. We have all these amazing things that are building on the work that we’ve done in the past that are going to once again make the city better in these gaps that we see. We can actually address them, and we have support and interest in the city and the state behind us. And we’ve delivered on a lot of things.

And internationally, that’s opening up, so now we can take our local artists and move them around and make them international artists. There are other people that we’ve identified that have the same illusion we have, but they’re in Ghana, they’re in Paris, they’re in Australia, and we can build on this infrastructure and really start to do some really fun things. Right now, we’re building out our foundation. We’re looking inward a little bit to make sure we’re ready for that next —

Andrew: I’d also say the mission is really not about us.

Faheem: That’s right.

Andrew: If our passion is the thing that’s driving it, then that in a way is pointing back at us. You asked how someone could think about doing this in their own city. I think if we’re serious about the mission, it has to somehow become externalized in an intentional way so that we may be filling a role within the mission and the structure but our passion is not the thing that’s catalyzing or driving it, so that other people have access, can plug in, have a way to direct resources through the mission to realize their own agendas.

Because it’s not about us realizing our agenda. It’s about us developing frameworks and tools for other people to realize their own agendas and get resources and feel safe and stable in their lives to achieve those things.

Pier Carlo: You must be aware, though, as an organization gets larger and brings on more staff, it loses its nimbleness.

Andrew: Well, that’s what we’re working on.

[They both laugh.]

Faheem: That’s what we’re trying to figure out.

Andrew: That’s exactly it.

Faheem: Yeah. That doesn’t necessarily mean it’s a bad thing, but it’s a thing to consider about —

Pier Carlo: Right. Being less nimble doesn’t mean it’s calcified necessarily.

Faheem: Right. But also it’s like, yeah, maybe it doesn’t need to get bigger. I’m not saying one is going to definitely turn into the other, but so often, especially in a capitalist society, bigger is better. And that’s not always the case. It depends on your metric, your measures.

We don’t measure our success based on butts in seats, ticket sales. Sometimes the best programs we’ve had have been with two people, and a lot comes out of those two people, that relationship. You can have a really intimate conversation. You can’t have an intimate conversation with a thousand people. We’ve always challenged measurements and rules and why things are the way they are before we do things.

When we sometimes fall into those trappings, the benefit of having the four of us is that one of us oftentimes is going to push against the fray and say, “Hey, well why are we doing that?” Then we have a frustrating conversation, and we figure it out. But the journey is the point. The journey — whether it’s, small, big, whatever — is what I don’t want to mess up.

Pier Carlo: I’m thinking, though, that funders love to read about impact and measurements.

Faheem: Oh yeah, they do.

Andrew: I agree. I think funders have to develop measures and frameworks for themselves because they need a way of evaluating who to fund and the returns, the ROI on that funding. But I would also say some of those structures, because they’re conceived in advance of giving money, can also be just like any structure, a preconception about the way that ought to work. I think we’ve had a lot of really amazing success in, just like we would with a constituency in the city, talking with a funder and developing trust and sometimes talking about the way those structures inhibit the kind of change that we want to make.

And exactly what you brought up: When an organization gets bigger, sometimes the laws and requirements force a certain kind of hierarchy. The question is, how do you navigate that as an organization to preserve the ethos of the organization without having to embrace a hierarchy just for the sake of getting money?

Faheem: Yes.

Andrew: And it’s a question.

Pier Carlo: So you’re in the middle of figuring all that out.

Andrew: Well, I think we will be perpetually ... . If your organization is successful, these questions are inevitable. And they should be. I think we enjoy them in the same way that we would enjoy thinking about a biennial as a medium.

Faheem: Yes, absolutely.

Andrew: Maybe an org is a kind of medium, artistic medium, and we can be objective about it and think about what it does, what kind of relationships it supports.

Faheem: To many of our funders’ credit, early on, we had these conversations about doing these spectacular things on the furthest reaches of the city that, depending on who you are, are unseen.

I remember one specific story. One of the places that we wanted to go out to is a space called Altgeld Gardens, which has this huge history. It’s public housing. The city is broken up by blocks, so this is at 130th; number one is downtown. So this is all the way out. I said, “We want to do a thing out in Altgeld Gardens.” I remember a gallerist funder said to us, “Well, who’s going to go out there?” I said, “Huh? What do you mean?” He said, “Well, you’re not going to be able to get anyone to go out there.” I said, “But there are already people there. And they’re already doing stuff out there. There’s all types of culture. You can come or not come.” We tell our funders that: “No, there’s no gala. There’s no fundraiser. There’s no event. The event is the event. You come to the event. The thing you’re supporting goes to the thing. Additionally, those budgets I was giving you, I want to give some other goals.”

One of our long-term goals is for every dollar that we put in infrastructure, we put into people. Whether that’s towards project programming, stipends, things, it’s a one-to-one. One of our long-term goals is to do a 50/50, so that’s why we’re a pass-through organization. The money has gotten more increased, but early on it was like, “No, you don’t do anything. You just do what you do. You don’t need to do something for the money; you’re already doing it. This’ll help you do it.” In the beginning it was just vetting. It was just like, “Hey, we’re going to come get off the barge. We’re going to come into town. There’s a bar. We’re going to put money on the guitar player. He plays the guitar that night, and he ain’t got to hustle for donations.”

Sometimes it’s just being seen that can do the most. The money is more of a gesture — the money has gotten more significant since we started — but that means a lot, to be able to do something and someone comes in and says, “Hey, I want to give you some funds just so you can do.” That’s what residencies are. You just do what you do.

Andrew: Sometimes that guitar player will say, “You know, I’ve been doing these things, and I’ve been thinking about a totally immersive environmental-music medium, and I’ve never expressed it to anybody.” And because of their practice, you know that they understand the nuances of what they’re saying. And it’s easy to think, “Well, if you had some technical support, some infrastructure, some space to practice — “

Faheem: That’s the Fab Lab. That’s what we’re trying to build now. It’s not just stipends but actual expertise.

Andrew: “If you could come to our building and fabricate some things, what could you make?” And it opens up unprecedented projects.

Faheem: So that’s where we’re going next.

January 08, 2024