Ka'ila Farrell-Smith

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

For painter Ka’ila Farrell-Smith, the land on which she lives and works is the raw material for her art, both metaphorically and literally.

In November 2016, ten days spent at Standing Rock, ND protesting the Dakota Access Pipeline and meeting and working alongside fellow Native artists changed her life. Ka’ila, who is Klamath Modoc, learned about the Jordan Cove Energy Project, a liquid natural gas pipeline that was threatening her ancestral homeland in southern Oregon, and in 2018, she moved to Modoc Point, where she jump-started a new chapter in her activism and artistry journey, scoring a couple of big wins in the first year. She created her “Land Back” series of paintings, in which she started incorporating pigments and minerals from the land around her into her paints, and she was successful in blocking the Jordan Cove Energy Project.

Now, in 2024, represented by the Russo Lee Gallery in Portland, OR, she’s had her work exhibited in museums all over the country, including at the National Gallery in Washington, D.C. One of her pieces is also in the Portland Art Museum’s permanent collection. On the activist front, she is suing the State of Oregon for illegal surveillance and is also combating lithium mining in Native regions of Southern Oregon and Nevada.

In this interview, Ka’ila explains why she left the artistic hub of Portland to live in rural southern Oregon and describes how her activism and artistry have evolved hand in hand.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- Were you nervous about leaving Portland and the access to galleries and different resources?

- Could you describe the first set of work you did that felt like you were at home, that felt like you had landed where you were supposed to be?

- What do you think in your artist self and spirit makes you a particularly effective activist?

- How do you make sure that you leave yourself enough psychic space to spend time in the studio and concentrate on your artmaking?

- Have you sought changes in the way you work with galleries, museums and collectors? Is there anything in the art world ecosystem that you would like to see reinvented?

- Can you describe your new series?

Pier Carlo Talenti: When you decided to leave Portland, were you nervous about leaving the city and the access to galleries and different resources?

Ka’ila Farrell-Smith: Yeah, it was definitely something I had to weigh. I was considering the questions and the thoughts about all of this, and — it’s been, what, six years now since I've left Portland — I think it was what I was meant to do. I followed that trajectory, that passion, and that inspiration for me was coming directly from the land and reconnecting with the land.

At that point in time, I was working with Signal Fire, which was a nonprofit artist-residency program. I was a certified Wilderness First Responder, so I was a guide and leading artists out on backpacking trips and camping trips in southeastern Oregon. On one of the first trips I led, we came here down to Chiloquin and met with another Klamath Modoc artist, Natalie Ball, and she took our group out on some hikes and walks out on the wetlands.

Basically, Chiloquin and Modoc Point are just 40 minutes south of Crater Lake on the Upper Klamath Lakes and the Agency Lake. These are these large lake areas up high in the mountains, and then if you go east from here, it's the Great Basin. There's just these large playas that were once big lakes, and it's high elevation, high desert. At that point, I think my art was really inspired by the land.

Pier Carlo: What does being a Wilderness First Responder entail?

Ka'ila: It's a big responsibility. It's basically like if there's any injuries in the back country, we're trained with first-aid medical training and basically how to log and take care of a patient until we can get them to medical treatment or to a hospital or to an emergency evacuation situation. That entails a 10-day training.

Anyways, during that time, I was starting to lead people on these trips, and that was really inspiring my practice. I was starting to harvest wild-harvested pigments. I'm a trained oil painter, and my body really hit a toxic level, I think, with the oil paints and the materials I was using in the studio, so I was also shifting in my studio practice away from oil paints and working more with acrylic-gel mediums and wild-harvested pigments in my studio practice.

At this point in time, I had been doing artist residencies myself. I graduated with a master's degree in fine arts from Portland State University in 2014. Those four or five years after graduate school, I was applying for artist residencies, like month-long ones. I did Djerassi outside of San Francisco, Ucross in Wyoming. I did the Santa Fe Indian Institute for American Indian Arts, IAIA, a month-long residency in Santa Fe. That was really beneficial to me because I had one month to completely just dive into my work and create a series within a month, a body of paintings.

So that was giving me that ability to continue my studio practice, whereas in Portland I was just really juggling multiple jobs. I was teaching at Portland State University; I was working as a guide with Signal Fire leading artists on backcountry trips; and I was also working in the studio, but I was able to produce so much more work when I was isolated in a residency program.

Pier Carlo: Could you describe the first set of work you did that felt like you were at home, that felt like you had landed where you were supposed to be?

Ka'ila: The first series that I made after relocating to my ancestral homelands, here at Modoc Point Studio, was called the “Land Back” series. That series was from 2019 to 2021. I was, again, mixing the wild-harvested pigments, like that charcoal from the wildfires across the lake at Pelican Butte. I would hike up at those lakes and collect that charcoal. There's this chalk in Klamath Falls that my dad used to say his grandma would eat, so I don't know if there's calcium in it, if it's medicinal. I ended up using that, mixing that with acrylic-gel mediums, as well as some of this red earth from the Painted Hills.

Then I was also collecting metal detritus, like metal objects that me and my partner Cale were finding. The land I'm on is 18 acres, close to the Upper Klamath Lakes. I'm right behind Chiloquin Ridge. It was juniper forest, ponderosa pine forest. It’s an old ranch land, so I was finding shot-up cans and weird metal grids, all kinds of funky machine parts that were on the land. I was stenciling those metal objects, these metal-detritus objects with aerosol spray paint. I had the full respiratory mask on, again, because I was wanting to protect my body from the toxins that are a part of some of the painting materials.

That “Land Back” series was really because I was fighting the LNG pipeline.

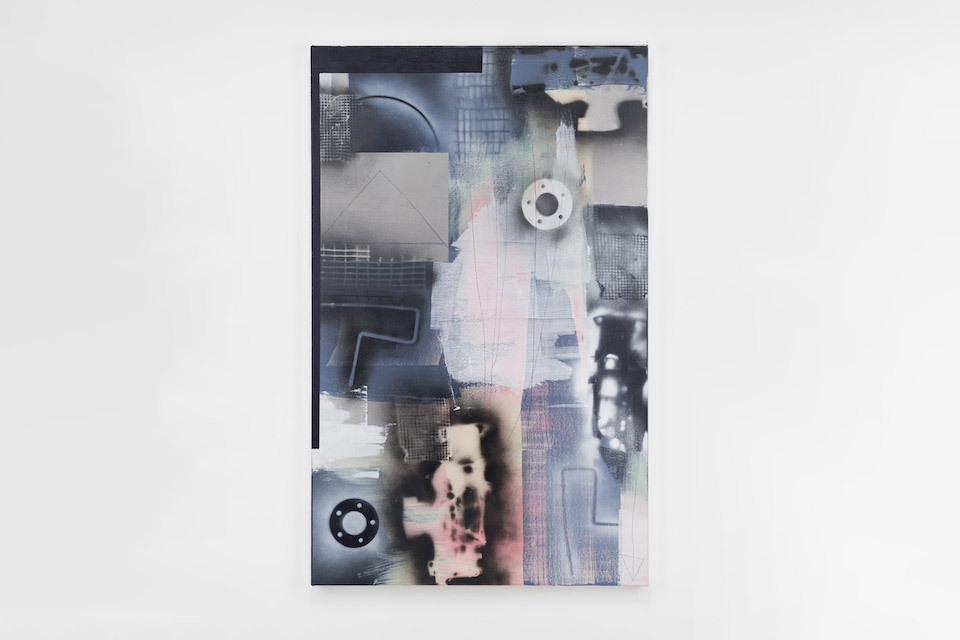

"Off the Ground" detail, 2021, 60 x 48 inches, Permanent collection of Portland Art Museum, Native American Art collection.

Pier Carlo: What do you think in your artist self and spirit makes you a particularly effective activist?

Ka'ila: Art and activism and how it's combined together has been the most difficult part of my practice, I think, for the last 20 years. After Standing Rock and moving home in 2018 and working on stopping the Jordan Cove Energy Project, I was forced for it all to combine together. And it really is combined together.

The other part of my practice is that I'm a writer. I actually have a chapter that just got published in a new academic book, which is about all of this. I actually write about all of my research, all of the activism work, and then as well as the art studio practice.

But with the activism, with Jordan Cove, I was offered the governor's show to show my art in the Oregon governor’s office. I used that as an opportunity. I accepted, knowing that I was going to not do it, to make a point. [She laughs.] I accepted the governor's show and then wrote a very effective letter, ultimately, of why I am opposed to the Jordan Cove Energy Project. It's a foreign corporation, a Canadian corporation, and at that point in time they had spent so much money on influencing our politicians and on propaganda campaigns, so mailing out huge fancy full-color mailers, just trying to make the Jordan Cove name be a positive name in the community. And it was very effective.

I think that's one of the big reasons why I left Portland: I was not finding really much support at all. There was a group of artists that came together, and we were doing bird-dogging. We'd know where the governor was going to be eating lunch, and we made huge painted banners with students at Pacific Northwest College of Art. We also had a collaboration with Just Seeds, which is a printmaking group of artists that work on the frontline campaigns. Just Seeds came, and we had beautiful screen-printed signs made. We had a really great activist art community, and we were showing up in Portland but also in Salem. We were doing protests in Salem.

It culminated with me declining the art show to the governor's office and then getting my letter published in The Oregonian and then in the Herald and News, which is the Klamath Falls newspaper. That was a big deal. Of course, it was reproduced online as well. So I guess that's how my art and activism came together to be successful.

Then once I moved back down here to Southern Oregon, I continued that work within my community. I was on fellowship for about the first three to four years while I lived down here, which made that move and transition really feasible because I had funding from state fellowship organizations through Oregon Humanities, Oregon Community Foundation. I was the Fields Artist Fellow. The Fields Artist Fellowship was really about working with youth in the community. So I wasn't depending on gallery sales at that time. I was on fellowship, so that was a really nice cushion to be able to transition my whole practice out of Portland.

Pier Carlo: What was the governor's reaction or response to your declining the show?

Ka'ila: At the time, it was Governor Kate Brown. She was always considered neutral on the Jordan Cove Energy Project, which I thought was lame, to say the least. [Laughs] She never actually responded. I think she then offered the show to another Native artist in Portland — her name is Brenda Mallory — but Brenda also declined the show to be in solidarity with me. At that time, the Klamath tribes were opposed to Jordan Cove. This was that month of November, Native American Month, and I think both of us declining it made a statement. They never really said anything. You know, politicians. They just ignore it and hope it goes away, I think.

Ultimately, our senator Jeff Merkley was the first one to flip. All of these politicians were pro-Jordan Cove, but through our pressure and through our public comments, we were able to flip politicians one by one. Ultimately, Kate Brown, our governor, had to be on our side because we ended up suing ... . The State of Oregon sued the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission or FERC, and I was the lead … . I wrote a letter. At that time, I was on the board of Rogue Climate, which is a big nonprofit out of Southern Oregon, and we were representing 700,000 people, and we had stopped every permitting process. The company didn't get one permit, so they were never able to put a shovel in the ground. We ultimately won, and Jordan Cove is dead.

Currently, I'm working on stopping the lithium mines in Northern Nevada and Southern Oregon, so I'm completely in another fight right now. But with Jordan Cove in the State of Oregon, we knew that they were illegally surveilling us through our phone, our devices and through social media apps. That's what I'm proving. Actually, up to this point, the judge — we have a new judge now — is siding with us, with the plaintiffs. The case is Farrell-Smith v. the State of Oregon DOJ. I'm following in my father's footsteps.

Pier Carlo: Because your father was also a plaintiff in an important lawsuit, right?

Ka'ila: Yeah, Al Smith v. the State of Oregon, and that was the unemployment division. It was a Native American freedom-of-religion court case that went to the Supreme Court in the 1990s. I was seven years old, and I remember going to D.C. for my dad's case at that time.

Pier Carlo: Through all this work, how do you make sure that you leave yourself enough psychic space to spend time in the studio and concentrate on your artmaking? Do you need to make an active choice to remove that other stuff and give yourself space to make your art?

Ka'ila: Yes. I've been as dedicated to my studio practice as I have been to environmental advocacy work my entire adult life. When I graduated from undergrad at the age of 21, I didn’t really like the combination of capitalism and art, and that part has always been really difficult. It's always been very difficult for me.

Pier Carlo: You're not the only one, you'll be happy to know.

Ka'ila: Yeah, exactly. So that was always something I've been trying to navigate. I went right into the environmental organizing, grassroots organizing, environmental advocacy work straight out of undergrad. I worked as a grassroots organizer and canvasser for about eight years in my 20s, and I really just focused mostly on that. Then I'd always paint, though. I'd always have a studio somewhere in my ... I lived in a lot of different houses and with a lot of different people in Portland for many years.

But now I have that dedication. I have a big studio here. I live in a log house at Modoc Point with a big huge greenhouse. We have a chicken coop, and I have a big studio. There's a barn and a lot of land, and I have a beautiful view of the mountains, so I'm constantly in a meditative state in my home here.

It's also really cold here in the winter, so I'm gearing up. I finished my series last year called “Ghost in the Machine,” and that was really a meditative series. I work on multiple paintings at once. I worked on 21 paintings over two years, and that series is called “Ghost in the Machine.” They're monochrome; they're black and white. Of course, I mix all my own blacks and grays, and I have that wild-harvested topsoil from the lithium where the lithium is in the high desert east of me. That whole series is really about bringing awareness to the lithium mining and what that's going to be if we don't stop it, because it's terrifying.

Yeah, I'm doing the activism, doing the work, the community work, but I'm also harvesting the materials. I'm thinking about the paintings. For me, that is that meditative healing space that I need personally for myself to be able to be balanced in the wake of taking on such heavy work in the field.

I'm getting ready to start my next series of work. It's starting to get a little bit warmer. I just have to wait because I do have a fireplace in my studio but it is really cold out there, so I usually start painting once it gets a little warmer out. In the spring months, I'm just plugging away.

"Ghosts in the Machine, 020," 48 x 36 inches, 2022-2023, Northern Paiute lithium topsoil, acrylics, aerosols, and graphite on stretched canvas. Photographed by Mario Gallucci photography.

Pier Carlo: Oh, my gosh, it sounds so beautiful.

Ka'ila: It is. It's a harsh place, but it's also just very powerful and inspirational as well. I just wanted to make one more point about what brought me home.

Pier Carlo: Go ahead.

Ka'ila: I just want to bring it back to my father because my practice is really linked to my father's life, his experiences, especially with colonialism and settler colonialism in the State of Oregon. My father was elderly during my childhood. Al Smith, the late Alfred Leo Smith, was born in 1919 here in Modoc Point, and he passed in 2014, so he was 95 years old. It’s been 10 years since my father passed. I was very close with him. My whole family went to D.C. I have my mom, Jane Farrell, and then I have a younger brother, Lalek Farrell-Smith. Me and Lalek are the youngest of Al's nine children, so we were born as a great-aunt and a great-uncle. We have lots of nieces and nephews, and I have a big family. I'm an auntie to a lot of people down here. So that's been beautiful to reconnect.

But it really was, for me, about bringing my father's ashes back home because the hardest thing for my father was to return back here. He was ripped away from his grandparents and mother at a very young age and put into the boarding-school systems. Our tribe was terminated in the 1950s, so we actually don't have a land base. We don't have a reservation in Klamath. There's a lot of historical traumas, and it was really difficult. For my father and the Chiloquin during those years, it was really hard after termination.

When I brought my father's ashes back home, I put them into the Williamson River, which is where he grew up playing. I live about five miles from where my dad grew up, which is our ancestral homeland, which unfortunately was sold or stolen at a very ... . It's a sad story, but I wanted to relocate my life and my practice and my focus back here where my people are from, my family's homeland. I can go and visit, and I also go and take care of my family's grave sites, which is something we do for Memorial Day. Every year, we go and clean them up, and everybody goes and visits the ancestors. I just wanted to put that in because I think that's a really important reason for why I moved back home.

Pier Carlo: Sure, absolutely. Part of your activism is really about stopping colonial methods of extraction. I want to talk about the art-world ecosystem, which many would say is extractive as well, and ask you if you've sought changes in the way you work with galleries, museums and collectors. Is there anything in the art world ecosystem that you would like to see reinvented?

Ka'ila: I guess how I've done that is through how I've sold work to museums. I guess I'll just start with a painting. It's called “After Boarding School: In Mourning.” It's a portrait I created in 2011. It's based off an Edward Curtis photograph of a young girl called “Mojave Girl.” I basically painted it in color, and I ended up chopping the hair off of it because when the Native kids were taken from their families and put in boarding school, their hair was chopped off. They were forced to speak English, wear the American clothes or the boarding chool outfits or whatever.

My dad always described the boarding-school era for him because he went to many different schools, including Chemawa, which is still in existence here in Oregon, and then the Stewart Indian Boarding School, which is in Carson City, NV. I just say that because my father was really close with the Paiutes, the Shoshones and Bannocks because I think he played on the sports teams during the boarding school times.

I made that painting, and it was purchased by the Native American Art Council [at the Portland Museum of Art]. That piece was brought into the permanent collection in 2012. I was just starting graduate school at that time, so that was interesting. I was selling a piece to the Portland Art Museum collection but also going through graduate school, which was interesting because in graduate school, they're trying to break you down and make you not paint anymore. [She laughs.]

Pier Carlo: Oh, wow.

Ka'ila: [Laughing] I feel like graduate programs are just traumatizing, and then you come out and then you figure out what your voice is or something like that.

Anyway, at that time, I was giving trainings. I was doing art talks in the massive auditorium in the Portland Art Museum to the docents. So this is where you have these issues within these museums, at least for me. I have this long relationship with the Portland Art Museum because PNCA used to be the art school that was affiliated with the Museum, so I know the Portland Art Museum very well. I know the collection.

I just had these deep critiques of the Native American art collection in general, how all the lights are dim, how it’s all baskets but there's no individual names of the artists, whereas basketry is extremely individual, the intimacy and weaving of these master baskets. It's an incredible collection, but it's like the whole design of the Native American art collection is that there's no individuals, it's in the past, and you just kind of study it. There really wasn't any or very much contemporary art in the Native American art collection.

Around this 2012 time, the museum was starting to change, so I ended up training the docents who are all volunteers. The docents are volunteers, a lot of them are elderly, a lot of them are white. I don’t know what the term is. I don't want to be like —

Pier Carlo: We can picture the stereotypical docent. We got it.

Ka'ila: OK, yes, you get what I'm saying. So there's elderly volunteers. At that time, I was also working for a camp called Journeys and Creativity, which was based through the Oregon College of Arts and Craft. Unfortunately, that art school is now closed too. You can see why I moved. The art schools started closing down. There were just big changes happening in Portland. But at that time, it was a camp for Native American students aged 15 to 19. It was a two-week camp, and it was at this art school, and it was really cool. It was fun. I worked as a mentor for these students.

I would take groups of students — they're all Native kids, brown- and black-skinned children and young people — to the Museum, and they would get harassed by these docents. It was really frustrating to me. When I had the chance to train the docents, I told them, "You all need to stop chasing us around the museum." It was just really uncomfortable because then the kids don't feel like they have a place or they're welcomed in the museum. So I've done that kind of work.

I've also been on steering committees for the Journeys and Creativity camps, so I’ve dealt with the presidents of these art schools. It takes a lot of effort and time. It just takes time to make real internal changes within institutions. I think I've had the community behind me.

I also sold a painting to the Jordan Schnitzer Museum of Art, which is in Eugene. That was a really interesting experience because they tried to low-ball me on the cost. I was like, “No, I know this painting is worth at least this much,” and I didn't budge. I've had to learn to not get pushed around, you know what I mean, and hold my ground when it comes to sales. I've had to learn all of that on my own or just make it up because they don't teach you that — the business, how to hustle — in art school.

Pier Carlo: It makes me think that artists who come straight out of graduate school and are completely untrained in the business side of things are really easy pickings for collectors, museums and galleries, right?

Ka'ila: Yeah. So that's the thing. It's like, “What school did you go to?” I don't know. I graduated from a state school, whereas I've seen other artists who graduate from Yale programs or Ivy League schools get a totally different opportunity straight out of grad school than I was offered, I guess. But then again, I've also been really ... what would be the word? I bounce back and forth between when I'm making art and working to be in that art world and then also being like, “I'm running off to the desert, and I'm going to go find my people in the Paiute, Shoshone, Bannock homelands. I want to go back and go to sweat lodge and return to the land and just camp out.” That fills my spirit, and it feels almost like a purpose. That's where I get inspiration to make my next 21 paintings.

Pier Carlo: You mentioned you were starting a new series. Can you describe it?

Ka'ila: I'm joining a collaboration this year. The next work that I'm going to start is part of this. It's called “Oregon Origins Project,” and it's a collaboration with composer Matthew Packwood through Reed College in Portland. He is creating a collaborative work. It's all about the geological events that created Oregon, and I'm going to be focusing on Crater Lake, which is basically the Cascade Mountains.

There's going to be music compositions, but I think there's maybe a handful of visual artists, and our work will be visually behind the orchestra. I'm not quite sure. I'm right now reading the updated contract, [laughing] and I'm going to sign it, but I thought that this was good because it'll give me something to focus on. Going deep into the heart of my homelands is Crater Lake, and it's epic. I don't know if you've ever been. It's one of the most incredible places in the whole world, and I live just right ... It's right here.

Pier Carlo: It's on my bucket list.

Ka'ila: You got to make it up there. I don't know, it's been calling to me. Anyways, I was up there. We had family visiting, so we take family up there. You can hike all the way down, and I jumped in Crater Lake for the first time. There's mythology around it. Gii-was is the Klamath word for Crater Lake. Only medicine people or First Vision Quest spiritual people would go up there. So there's a taboo to ... . You have to prepare yourself to go up to Crater Lake, to gii-was. It's very interesting. I'm thinking molten lava, fire, lava, reds, oranges, and then deep, deep water. It's the deepest lake in, at least I think, the upper states. I think it's a really amazing place.

April 15, 2024