Zeke Peña

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

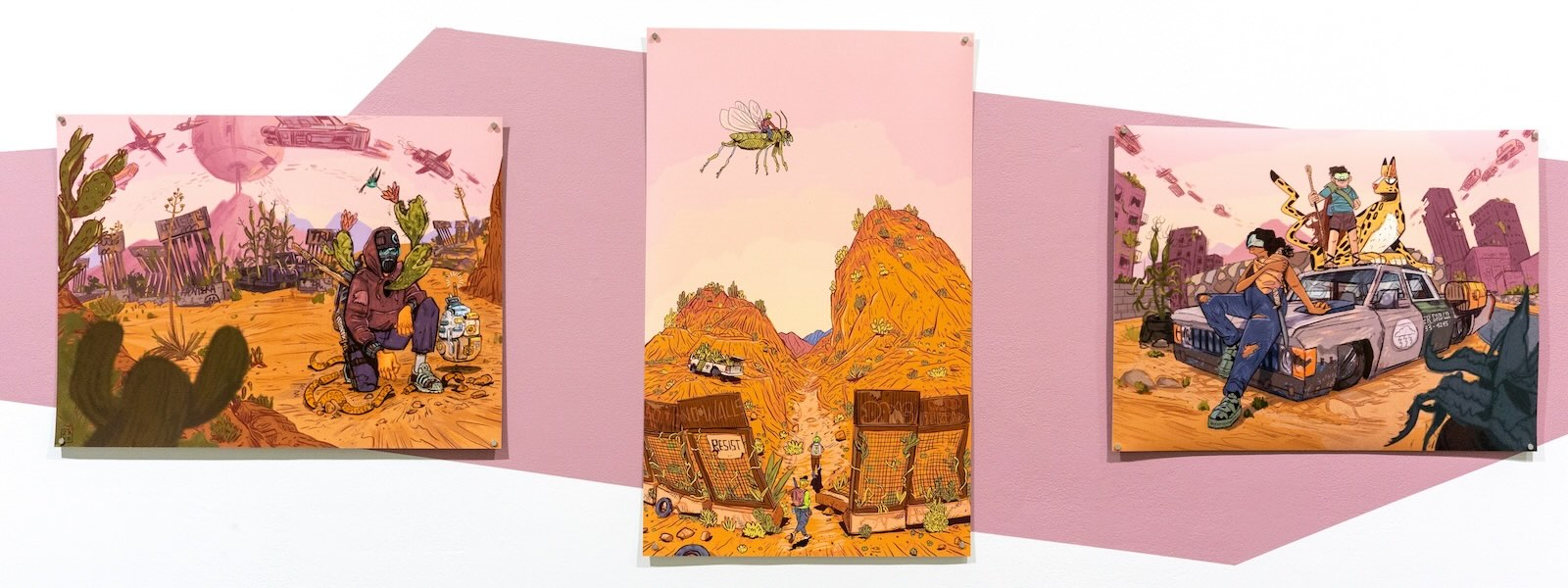

Zeke Peña is a Xicano cartoonist and illustrator who, for most of his professional life, has focused on the lives and stories of El Paso, TX, where he grew up and lived for decades. A self-taught artist with an undergraduate degree in art history from UT Austin, he has built a rich portfolio of varied works that, as he describes them, are “a mash-up of political cartoons, border rasquache and hip-hop culture.”

He has illustrated several award-winning books, including “My Papi Drives a Motorcycle,” which The New York Times called a best children’s book of 2019, and “Photographic: The Life of Graciela Iturbide,” a Boston Globe–Horn Book Nonfiction Award Winner and a Moonbeam Children’s Book Gold Award Winner. Both were written by Isabel Quintero, who has become a close collaborator. In 2023 he illustrated bestselling author Jason Reynolds’ “Miles Morales Suspended: A Spider-Man Novel.” His editorial work has appeared in a wide array of publications, including VICE, ProPublica and Latino USA.

Here he describes the evolution of his ambitious journalistic endeavor, “The River Project,” about the increasingly politicized Rio Grande and all it represents. He also discusses how he’s adapted to the latest moral book-banning crusade and how he wishes for publishers to honor their writers’ and illustrators’ collaborative spirits.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- Earlier on in your career, you were making large-scale paintings. What made you want to concentrate on the graphic work that now forms the basis your career? Was it a financial or artistic decision?

- When did the idea for the “The River Project” start cementing in your brain? And how has it been growing through the years?

- What have you yourself discovered through your art in the process of this project?

- Do you have a plan to publish an accumulation of “The River Project”? What’s your overall goal for it?

- You’re making illustrations, which throughout the decades whenever there’s a moral panic in this country, are the first thing that moralists target. What’s it like for you to make your work in this particular social and political climate?

- As technology keeps evolving, how do you think you’ll be using more technology both in your artmaking and also in the promulgation and display of your work?

- Is anything in your fields, whether in how you make work or how you get it out to as many eyes as possible, that you think could be reinvented or be made to work much better than it currently is?

- In her foreword for “My Papi Has a Motorcycle,” Isabel Ortega talks about how grateful she is for the work and research you did to bring her vision to life. Could you talk about your conversations with her in creating the book?

- As for your own artmaking, your own self-generated work, is there a big-picture project that you’ve got an eye on completing in the next few years?

Pier Carlo Talenti: Earlier on in your career, you were making large-scale paintings. What made you want to concentrate on the graphic work that now forms the basis your career? Was it a financial or artistic decision?

Zeke Peña: It was probably both. It was a financial decision, a personal one, a creative one. It had to do really with everything. At some point, I was making these large-scale four-foot paintings and augmenting them with video and audio and doing interviews and doing a lot of storytelling work, but I was painting it on a large scale, and —

Pier Carlo: Oh, so your paintings had these other storytelling and technical elements to them already back then?

Zeke: Yes. That’s certainly where I was working on storytelling.

Pier Carlo: The journalism never left you. That was always part of your work.

Zeke: Oh my goodness, never. And I think I’ve only become aware of that as of the past three or four years that, oh, this is like a journalistic thing that I’m doing. I’m interested in doing oral histories, I’m interested in hearing people’s stories, and then of course in telling stories. I think, yeah, you’re right to say that that never left.

Because for me the story was the most important thing, painting a four-foot oil painting is not the most efficient way of telling a story. That was probably the main reason, the efficiency. You can take two weeks to two months to paint an oil painting to tell one story, or you can draw it in a more simplified cartoon style and have the same impact and tell the same stories.

At some point, I also realized that I felt obligated to paint that way. I felt obligated to paint realistically. It’s what I was always taught that art was. It’s what I studied in school. I had a few professors that were into the graphic arts, which is what I always gravitated towards: printmaking, Chicana printmaking and all of that stuff.

Pier Carlo: Right, that long tradition.

Zeke: That long tradition. But the things that you go to see in museums are the oil paintings. You see all of the master oil painters, and so I realized that I was painting this way out of obligation, not to mention that it was more expensive and it took more time. It takes a lot more space to store that work and ship that work and all of those things. Also, it’s using really toxic materials. There was just a lot of reasons why I was like, “Oh, this is probably not the best for the work that I’m trying to do.”

I just made the jump, and I never really looked back. I feel so much more comfortable making the work that I’m making now. I just feel like it’s coming from an honest place.

Pier Carlo: I really want to talk about “The River Project” because of course it’s about the southern border, which has become such a cultural and political flashpoint now. First of all, when did the idea for the whole project start cementing in your brain? And how has it been growing through the years?

Zeke: I’m going to try to be as concise as possible. It’s sometimes difficult for me to discuss this project because there were so many iterations and it was such dense and connected work. One thing connected to the next thing connected to the next thing.

I had always been focused on my region. Certainly the border is a theme in my work or a topic of research in my work.

Pier Carlo: The region being specifically El Paso, right?

Zeke: Yeah, Paso del Norte is what it’s called today, which is the region of El Paso - Ciudad Juárez and the Ysleta del Sur Pueblo, which is an Indigenous sovereign pueblo there. That’s the region that I’m talking about. You can’t miss it. It’s a big part of our lives growing up there, depending on which side of the border you grew up on. I should be clear that I grew up in the United States. I’m not an immigrant. I’m second-generation on my dad’s side, and then my mother’s family is from southern New Mexico, where they’ve been living for many generations. That being a part of my personal life, I think, is why I gravitated towards the story.

I think what cemented the story was focusing on the issue of human rights and border crossings at the time. This is many years ago. I think 2012 or 2013 was when I started to look at what was going on. It was not getting a whole lot of media coverage at the time. It’s so prevalent now and so covered now, right, I think sometimes to a fault. At that time, I was focused on that and just started having discussions.

I got a grant from the Museum and Cultural Affairs Department in the city of El Paso, TX. From getting that grant, I collaborated with a group of friends: Claudia Ley, Sandra Iturbe, Carolina Franco. There were several friends, including my partner, that were aiding in this work and helping this work along its way. I just started having discussions with people, talking about their experience with the border and with the river.

The first iteration of that work was titled “Waterbound.” I made a series of paintings, and there were audio interviews that we performed and video interviews that we took to get people’s oral histories about the water. I think that was really where it started. After you start asking people about the river, it’s such a fruitful topic of discussion because it generates a lot of emotion in people.

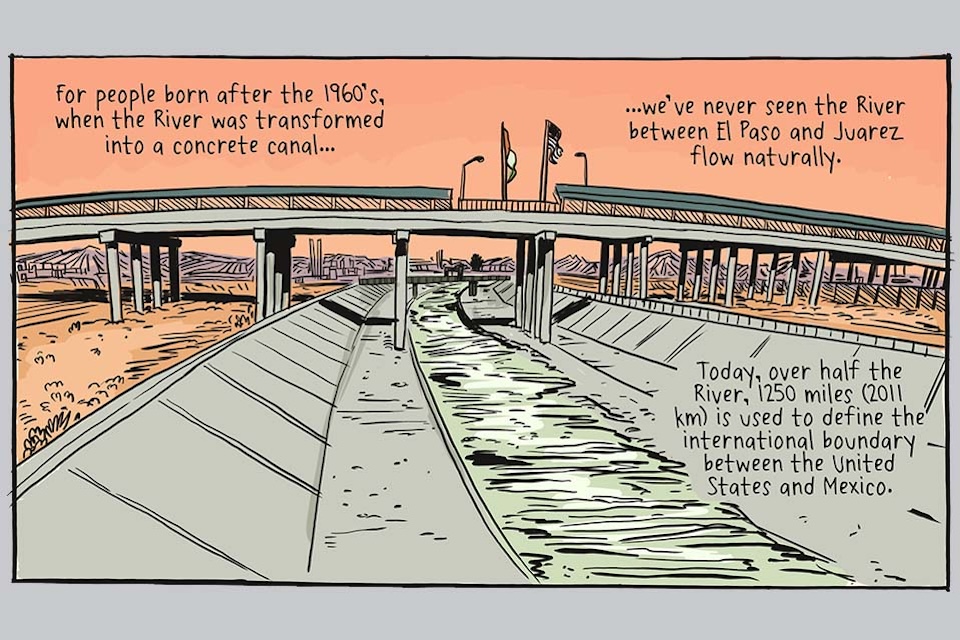

I think what really started the river work was that in those discussions with people, in those oral histories, there was a really clear generational shift that happened from one generation to the next with regard to the relationship of the river. We were speaking with elders in our community, and those elders had these really significant, beautiful stories about going to the river and fishing in the river and swimming in the river and sitting by the river and having parties and things like that. Then one or two generations later, which is my generation, we have no relationship with the river. The river, if I’m being honest, was always just the border to me, right? It was always talked about and discussed as just being the border.

From the “River Stories” comic by Zeke Peña; originally published in 2019. Edited and republished March 2023.

Pier Carlo: And physically inaccessible in a way that it wasn’t for older generations.

Zeke: Exactly. There’s this cognitive dissonance also in addition to that physical distance that’s created as a boundary. And also how the border is a unilateral thing. The border is owned by the United States. Mexico doesn’t put up walls and things like that, right? People that live on the side of Ciudad Juárez, they can still walk up to the river. It’s prohibited now because people get shot and it’s very militarized.

I think that generational shift was really what was the spark for that story. And trying to understand it for myself. It’s not anything more than me just trying to understand personally, why is it that I think about the river this way? And why is it that I didn’t have a better relationship with the river that has sustained my family for generations? That’s really what the work is looking at, and then talking with other folks from different areas and different regions and hearing more about what they have to say about it.

Pier Carlo: What have you yourself discovered through your art in the process of this project?

Zeke: For me personally, it’s uncovered a lot of my family’s history, going into archives and things like that, learning about where my family comes from, because the border has severed a lot of my familial history. On my dad’s side, I can’t even go one generation; I can’t go past my grandparents. I didn’t know where my great-grandparents were from before I started working on this project, and then after researching, it’s like, “Oh, there it is!” They come from a completely different place than I thought they did.

Pier Carlo: Oh. Had your father himself not known that history?

Zeke: Not even. I have some audio recordings. These are not from this project, but I’m a historian so I was always going to my grandparents and recording them and asking them questions and documenting. I have some cassette tapes of my grandfather talking with me and my dad. I told my dad that I wanted to go talk to my grandpa and ask him about where we come from and where he’s from, and he shared with us stories that my dad had never heard. You hear in the cassette tape how more and more of the questions start coming from my dad as opposed to coming from me, because my dad, he just grew up in a household where they didn’t talk about that kind of stuff, where they don’t share that kind of stuff.

Pier Carlo: It’s an immigrant reaction. You want your kids to assimilate.

Zeke: Absolutely. Oh my goodness, absolutely. Yeah, on both sides of my family that’s the case. I think that what we do with the intent of assimilating is we sever ties to where we’re from; we sever the roots of where we’re from. I think that that’s what I’m trying to mend. I’m trying to heal from that, if I’m being honest.

Pier Carlo: Did you illustrate that moment of your dad asking more questions than you?

Zeke: I haven’t yet. I’ve made work about my dad, and I’ve made work about my grandpa. I think that story will come eventually.

Pier Carlo: Have they seen the work? And how have they reacted to it?

Zeke: They haven’t. I never had the pleasure of my grandfather really seeing my work. He passed away, and then my dad also passed away suddenly about 13 years ago. He saw some of my work, but I don’t think he ever saw these projects that I’m working on, at least not in this realm. I like to think that he’s witnessing it from a different perspective.

Pier Carlo: Well, how lucky that you were able to witness him asking those questions, for your sake and for his.

Zeke: Yes, that was such a special moment, knowing that he also wanted to know but just never had the time or maybe the courage to ask. I was happy to be that little connection. And I think that that’s the motivation for this work, just trying to help us reconnect, just trying to help people reconnect to their history, and that’s been through the river. When you start asking people about the river, they really start reconnecting because water is memory. The river remembers what we’ve been through, and the river remembers what the area has been through, and so when we start turning our attention to that, the memories flow.

Pier Carlo: Do you have a plan to publish an accumulation of “The River Project”? What’s your overall goal for it?

Zeke: That project’s been on pause for a little while. I think that I’ve taken a step back from documenting people’s oral histories. I’ve really turned to my own family’s history because I think I have the most license and agency and right to tell that story. I started to question a little bit the gathering … because a lot of that work can be really extractive, right? That oral history work, it can be extractive, so I’m trying to rethink that process and how best to move forward with it.

But I do know that from a personal standpoint, I do have intentions of publishing the stories that relate directly to my family and to the river because, yeah, I literally learned my family’s history by looking at the river. Researching the river is what helped me understand where my mom’s family comes from in that region and where my dad’s family comes from.

Pier Carlo: In my eyes, you’re writing in the genre that is in a way the most dangerous. You’re making illustrations, which throughout the decades whenever there’s a moral panic in this country, are the first thing that moralists target. Because children like illustrations. I think we’re seeing it happening with book bans concerning books, especially illustrated books, that deal with in any way about race, the border, LGBT issues, etc. What’s it like for you to make your work in this particular social and political climate?

Zeke: Yeah, I don’t think that I have the objectivity to quite reflect or say something poignant or enlightening on it because we’re witnessing it right now so I can only reflect on how it’s changed.

Pier Carlo: How it’s feeling.

Zeke: Yeah, how it’s feeling, exactly. How is it feeling now? I think I have to ask the question, “Has it changed the way that I’ve told any story? Or has it changed whether or not I tell a story?” I can honestly say that it probably has. I think that I have shied away from things for fear of my safety and my family’s safety. I’ve maybe tried to be more creative in the way that I’m delivering certain things.

Pier Carlo: Can you give me an example?

Zeke: For example, I don’t use a whole lot of words in my work anymore. I’m telling story through images. People either understand the visual language or they don’t understand it. I make work for the people who are closest to me in my community. First and foremost, that’s who I make work for because that’s the voice that I know how to speak in best. Then I hope that other folks can engage with it and read it and understand it and take away something from it.

But I can’t say that I write with the intention of everyone understanding my work because that’s a just not going to happen. It’s not possible, right? You’re always going to exclude someone. Everyone’s always going to exclude someone by telling a story, and so I do my best to be inclusive and I do my best to be extremely accessible by using simplified images and simplified iconography. I think that’s one way it’s changed it, I would say.

Pier Carlo: I love that you were using AR, it sounds like, over 10 years ago. As technology keeps evolving, how do you think you’ll be using more technology both in your artmaking and also in the promulgation and display of your work?

Zeke: Yeah, thanks for that. Technology’s always been of interest to me. I started doing 3D animation in high school and stuff when it was very first coming out, and so it’s always been something that has interested me. It helps in the development of work. It speeds up the process of development. You can sketch and change and rescale things on an iPad so much more quickly than you can by erasing them and redrawing them on a piece of paper.

That being said, I still always start with pencil and paper because it’s what I feel most comfortable doing. My hand knows it. I drew on pencil and paper for 20 years and then started using this iPad thing or tablet thing. It’s just like a comfort thing.

But having that interest in technology, I think that especially for this generation now — I shouldn’t say this generation; let’s just say this moment that we’re in right now — where our phones are attached to us and our eyes are buried in the screen, it’s about trying to meet people where they’re at. I think our brains require a little bit more. Sometimes we want to see more, so if you can make a print make sound or you can make a print move on your device on augmented print, it’s just another avenue for someone to engage with the work who may not have been intrigued by the static image. I certainly think that, thinking of my nieces and nephews now and my son, their brains and the way they experience the world is much different. For young people, just trying to find ways of creating more doorways for the work, right? While the sound and the movement may not be critical to the narrative or the story, it may give someone else a way for the work to resonate.

I work with Augment El Paso, a friend’s company that has done all the augmentation for the augmented prints and the augmented paintings that I’ve done. It’s an excellent way to deliver history. The augmented paintings were something that we worked on, and he made the paintings move and added the audio interview of the person that was in the painting. That just adds this whole other element of experience, for someone to hear the story in the person’s own words. You can’t get much more direct than that, right? Having a first-person account with the added benefit of having a nice painting to look at. The painting is just the vehicle; it’s the least important thing. I think the augmentation really adds that element.

“Cruising” by Zeke Peña, 2018; Cover Illustration for The Believer magazine featured on the June/July “Summertime, Oh Summertime” issue.

Pier Carlo: I love to talk about how artists reinvent outmoded systems in their fields, especially since the pandemic. I’m wondering if there’s anything in your fields, whether in how you make work or how you get it out to as many eyes as possible, if there’s any system that you think could be reinvented or be made to work much better than it currently is.

Zeke: Oof, there are several that come to mind. The first one, because I do a lot of work in publishing, I certainly think that access to publishers is an issue, especially for storytellers that may or may not have the training, representation, knowledge to access publishing.

Pier Carlo: How did you make your connections?

Zeke: It was through the back door, definitely. I always say that, that I got into publishing through the back door. It was on a whim. I had always wanted to make comics; I had always wanted to make books from a young age. The work that I was making, especially the illustrated and cartooned work, the comic work, was always made with that intention of eventually being able to publish, but I was that person. I had no knowledge of how you do that. Who do you talk to? Who do you email? How do you even do that? How is it made? I didn’t know anything about the process.

I think that we could be doing more, even just on a high-school level, to give young people the knowledge or just courses or experiences or workshops or things like that so that if they feel like they have an important story to tell, they know how to publish it. Fortunately, I think technology and access to the internet and self-publishing are really changing the way that publishing is working. People who are self-publishing are then going on to make deals to be republished.

Pier Carlo: Oh, I didn’t know that!

Zeke: Yeah, that part’s changing. It’s not an ideal situation for a publisher to republish work, but I think they do a calculation on how spread was the publishing. I think that that access, the pathway to accessing publishing, is opening more, but I think there’s certainly an issue with creative directors and art directors and who they’re reaching out to from an illustration standpoint. Yeah, it’s just tough.

I think that system, publishing, is very outmoded. It’s very archaic in the way that it works.

Pier Carlo: Still now. That’s amazing.

Zeke: Still now, yeah. I think that there’s a more collaborative way that you can make books that is sometimes happening with certain publishers. I certainly don’t think it’s always happening. Something that I mention to people is, “Sometimes an illustrator never even talks to the author who’s worked their illustrating.” That blows my mind. I’m like, “What? How? How is that the thing? How is that the way that it works?”

Pier Carlo: And surely the author doesn’t enjoy that either. Is it just the publisher trying to run interference just to keep things simple?

Zeke: I think it’s a simplification thing. It’s probably an efficiency thing. I’m sure they’ve done their calculations. A lot of it has to do with control, let’s be honest. They can control the narrative and control the story, which I think is fine. But if our intention is for people to get their honest, genuine story out there in the world, that maybe isn’t the best way to go about it. It’s with transparency and accountability. How can we be transparent about this process and accountable and collaborative? I think that’s certainly something that’s outmoded.

Then on the fine-art front, it’s certainly access to museums and galleries, institutions, history museums and things like that. It’s letting the community have a voice for what is represented in the space and letting the community inform the spaces that in a lot of places they’re paying for with taxpayer dollars. Our experience in El Paso is that there’s such a gap between the community and some of the institutions there, the art museums and the history museums. Certainly, that’s changing now. Fortunately, a lot of that is changing.

But to go to a point that I was talking about before, I’m certainly not the only one that’s trying to reconnect to where I’m from and reconnect to my history. Can you imagine if we had these more open and accessible spaces that serve the people that are paying for the space by showcasing inclusive stories for many communities and stuff? Imagine how transformative that could be. I think that the access to that space is something that’s of value. Where do we gather as a public and as a community in space anymore that’s not centered around sports, that’s not centered around going to watch a movie, that’s literally generative?

Pier Carlo: Or staring at a screen.

Zeke: Or staring at a screen. Where do we go to gather in those spaces? There aren’t many of them. I think that museums — I’ll include theaters in this — these spaces could be perfect for that kind of gathering and balancing out both things. I think that that’s something that I think could change and that is certainly outmoded. The hierarchical structures of institutional administration, I think, are outmoded and I think could certainly benefit from creating some bridges to the communities that they serve and that they exist in and that they’re, in a lot of cases, being paid for by.

Pier Carlo: You mentioned that oftentimes illustrators and authors are not permitted to speak to each other. But clearly that was not the case with “My Papi Has a Motorcycle.” In fact, in her foreword, Isabel Ortega talks about how grateful she is for the work and research you did to bring her vision to life. Could you talk about your conversations with her in creating the book?

Zeke: Yes. She is right to point out that we even talked, you know?

Pier Carlo: Right.

Zeke: Both her and I were relatively unexperienced in publishing. Neither of us had any previous experience. We have this long history in coming into publishing at the same time that I won’t get all the way into, but we first worked with each other on her first book, “Gabi, a Girl in Pieces.” Because it was an independent publisher, they let us talk to each other. We texted; we shared ideas. Isabel sent sketches for certain things that are in her first book, and I recreated some of them, and so it was super-collaborative and super-open.

I’m so grateful that we had that experience, and it could have only happened at an independent publisher because they’re more open and they’re more collaborative and it’s less hierarchical. It’s all these things.

I think that that experience carried over into “My Papi Has a Motorcycle,” where we went into that book deal as a team. It was like, “I’m the illustrator; she’s the author.” That’s somewhat of a rare thing. Typically an author is submitting a story, and then the publisher buys the story and then goes and finds the illustrator, but we were a unique package deal. And I think that the book was better for it, right?

Pier Carlo: Do you have any plans to work together on a future project?

Zeke: Yes, certainly.

Pier Carlo: As a team?

Zeke: As a team. We’re actually working on developing some stories now, follow-ups to “My Papi Has a Motorcycle” that are in the same world but are different stories. Yeah, definitely, our collaborative process is a really great one. It’s a really good one that I’m grateful for, and so I think we both have intentions of continuing to work together.

Pier Carlo: As for your own artmaking, your own self-generated work, is there a big-picture project that you’ve got an eye on completing in the next few years?

Zeke: Yes. I’m working on a book right now that I’m writing and illustrating. It’ll be my first venture into being both an author and an illustrator.

That’s definitely the one that’s ... . It’s on my table right now. It’s what I’m sketching on right now; I’m developing the characters; I have a pretty solid draft of the story and the manuscript. I’m excited about that.

Pier Carlo: Can you tell more about it or not yet?

Zeke: I can tell a little bit more about it. It has not been announced yet.

Pier Carlo: So there’s a publisher?

Zeke: There is a publisher, yes. What I can share is that it’s a story of a brother and a sister that wake up one morning and watch something fall from the sky into the desert behind their house and they go on a journey in the desert to go find it.

Pier Carlo: Oh, that sounds amazing. Congratulations. I can’t wait to read it.

Zeke: Yeah, thank you so much.

February 19, 2024