Lacy Hale

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

When the devastating floods of July 2022 tore through the mountain communities of Southeastern Kentucky, visual artist Lacy Hale lost her studio and a trove of works in progress. Since that tragic and deadly night, though, even as many of her neighbors in Whitesburg have been forced to move away, one thing she has not lost is her determination to remain in the mountains where she grew up. They are in her blood, and they inspire her art, just as she intends for her art to inspire the people of her corner of Appalachia.

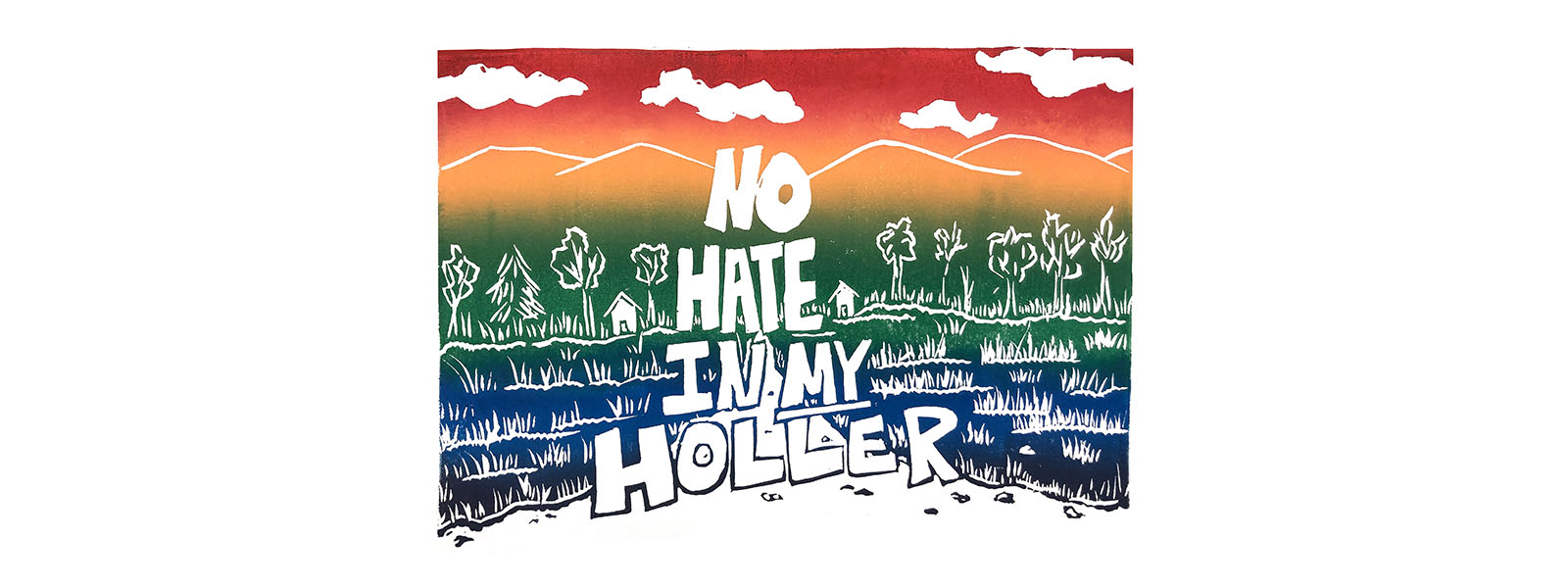

Lacy has been making art in Whitesburg since returning from her studies at Pratt Institute in New York City in the early 2000s, and it has become her full-time occupation since 2017. In addition to being a painter and a muralist, she is also a printmaker and over the years has created and sold an array of items bearing her designs. One of her most recognized designs is “No Hate in My Holler,” a graphic she created in 2017 in response to a scheduled neo-Nazi gathering in a nearby town. “No Hate in My Holler” quickly appeared on billboards and T-shirts and also became a popular hashtag, garnering attention from national media outlets.

Lacy’s murals can be seen in communities throughout Kentucky and Virginia. Among the honors she has received are the Eastern Kentucky Artist Impact Award as well as grants from the Kentucky Foundation for Women, Great Meadows Foundation and the Tanne Foundation Award. In 2016 she co-founded EpiCentre Arts, which supports and advocates for art and artists throughout the Appalachian Mountains.

In this interview with Pier Carlo Talenti, Lacy explains why and how her artistry is inseparable from her community and the landscape in which it nestles. She also describes that devastating July night and what it’s taken to recommit to her art, her business and her home despite losing almost everything.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- Can you describe your community for us?

- At what point in your childhood did you discover that art was your passion?

- What made you want to return to your community?

- What role do you want your art to play in the community, and what role does the community play in your art?

- What are the biggest misconceptions about where you live, and how is your art changing that?

- Can you describe "No Hate in my Holler"?

- What made you want to start EpiCenter Arts?

- How were you impacted by the flooding?

- What do you think would make it easier for an artist such as you to really commit to living and working in the town where they grew up or in any rural town that they want to live in?

Pier Carlo Talenti: We’re going to be speaking a lot about your community a lot, so I wonder if you’d mind describing it.

Lacy Hale: Sure. Whitesburg sits at the foot of Pine Mountain, which is the second tallest mountain in Kentucky. It’s in the Cumberland Mountain Plateau region of the Appalachian Mountains here in central Appalachia. It’s gorgeous. It’s one of the reasons I love this area so much. Growing up here, you could always run and play in the mountains and in the creeks, and there’s a lot of wildlife. It just lends itself very well, I think, to being creative and being artistic. It’s just a very, very beautiful place to be.

Pier Carlo: And your studio is downtown? What’s the town like?

Lacy: The town is a town of 2,000 people, so it’s very small. We have our courthouse and our lawyer offices, and then we have restaurants and a couple boutiques. And then we are lucky enough to have Appalshop here, which is the media organization that’s been around since 1969. It’s really kind of a cool little funky town in the mountains of Eastern Kentucky.

Pier Carlo: At what point in your childhood did you discover that art was your passion?

Lacy: Well, I remember when I was five years old and, I guess, in kindergarten, I drew a princess, a castle and a puppy, and I won the blue ribbon at the Gingerbread Festival, which was the festival in my hometown. I grew up 20 minutes from Whitesburg, in the next county over. I won the blue ribbon at the county fair, basically, and I was like, “Oh, this is pretty cool. This is something I like!” But I knew before that I loved art, and I think that just really bolstered my love for it then.

I grew up in a household that was pretty artistic. My dad played guitar. He could play basically anything that was stringed — my grandpa was the same — and he loved to read. My mom loved to read and do crafts. Two of my dad’s sisters were art teachers, and one of them wanted to be an author. I was surrounded by a lot of artistic people. I loved going to my aunt’s house when I grew up because she always had the huge sets of crayons and markers.

I grew up in a holler or a hollow. I lived up on the mountain, and then I could just run down through the mountains, down through the trees, down back to my grandma’s house, and then we could just go across the creek and get to my aunt’s house and go play in her art supplies. That was another reason that I loved growing up here: I was surrounded by relatives for most of my upbringing. My cousins and I were really close growing up, and we were always outside. [Laughing] If we weren’t inside making art or putting on plays or singing and dancing, we were outside making potions in the creek with sticks and twigs and mixing dirt and making mudpies and stuff like that. I knew I loved art from a very young age.

Pier Carlo: It must have been a big deal when you decided to leave for New York to attend Pratt. What went into that decision? How did you make it happen?

Lacy: From the get-go when I got into the art classes in high school, my art teacher was like, “This is something you should really think about pursuing.” I took every art class I could, and my guidance counselor was like, “Look, you should take anatomy; you should take biology. You should expand your understanding of the human form.” Then we were looking at colleges that had a good art classes and at art schools.

I grew up really poor, so I didn’t see how I could actually afford to go to an art school. I applied to a few schools, but I was accepted to University of Louisville and Pratt Institute of Art, so those were the two that I was considering. I got a full ride to U. of L., but New York was obviously the place to be [she laughs], and so I was like, “How could I make this work?” My mom was a stay-at-home mom, and my dad was a radio engineer, which sounds kind of fancy but he did not get paid very well, so we were trying to figure out how that would work out. My high-school art teacher and guidance counselors and people in the community rallied around me and helped raise money to send me the first year.

Looking back from this point and since then, once I moved back here, I can see how that has informed my artmaking ever since and how it has really made me think about my art in a way that I want to work in the community. Getting to Pratt was really my community believing in me enough and wanting to see somebody from here succeed. They wanted to send me there, and I got there because of them.

Pier Carlo: That’s amazing! Well, my next question was what made you want to return, but I can certainly see one of the reasons being the generosity of your community and you wanting to pay it back in some way, right?

Lacy: Yeah, it was that. And also I didn’t have enough money to finish my schooling up there. [She laughs.] It was really expensive. I was there for a couple years, and I had to come back home. But I did move away, not too far away, but three or four hours away from here.

I decided to make that the move back to the mountains because … . I have a design, “You’re in my bones like the mountains at home.” Because that’s one thing that if you’re from here, I think it just gets in your bones, and it’s hard to shake it for some people, especially when you’ve had those experiences like I’ve had with the community. I knew I wanted to come back and live here.

Pier Carlo: What role do you want your art to play in the community, and what role does the community play in your art?

Lacy: Well, whenever I did move to Pratt … and even sometimes if some of us from Southeastern Kentucky go to Lexington, which is three hours from here and still within the state of Kentucky, sometimes we get made fun of because of our accent. In New York, if I opened my mouth, people immediately thought I was stupid.

So one of the things I feel like I should do with my art is try to uplift the people in this region. I do a lot of printmaking; I do a lot of painting, fine-art easel painting, and I do a lot of murals. I see myself in my art. I want to help beautify our communities. I try to do projects, public-art pieces that also invite the community to be a part of those projects so there’s buy-in and they feel like they have helped plan and work on those pieces.

Pier Carlo: Can you give an example of that?

Lacy: Sure. There’s one I did in 2019. I worked with Southeast Community and Technical College in Harlan County. It’s a baby possum reaching for some ripe pokeweed berries. The community helped plan that. We had community meetings, we talked about what we wanted to see go up, and then the Harlan County High School students helped paint the mural. They did the underpainting, I laid it out in kind of a paint-by-number system so that they could help paint, and then I went and did the overpainting.

Then we had what was called The Mountain Mural Megafest so that community members could help. I did that mural on Polytab, which is a fabric parachute material that you put up like wallpaper, so the community could help install the mural too. On some of these projects I’ve worked on I’ve had parents come out and be like, “Can you tell me what part my child painted?” People are really proud of these pieces.

I just finished one up in Pound, VA of Granny Shores, who was a midwife who delivered over a thousand babies in the community in the early 1900s. They wanted to honor her. She is sitting in front of the mountains at sunrise, and she’s holding a baby. That was done on aluminum panels, and then underneath it there’s a quilt on her lap and around the baby. I gave community members some of those Polytab sheets and squares so that they could create their own quilt square. Different community members got to paint their own quilt squares to go on that piece so that they could feel part of it.

One of the Historical Society Members, Margaret — she was one of the oldest community members there, and she had been part of the planning from the beginning — I put her piece right next to the hand that was holding the baby. It really seemed to mean a lot to her. If I can do a piece of public art like that in a community and if it can make people proud to be where they are and where they’re from, that makes me feel like I’m doing something worthwhile.

Pier Carlo: What are the biggest misconceptions about where you live, and how is your art changing that?

Lacy: I think probably the biggest misconception is that we’re all white and straight. Appalachia is a melting pot just like the rest of the nation.

I did a mural in a town not far from here called Neon, KY. It’s about 20 minutes from Whitesburg. They wanted to honor their coal-mining heritage there. In the 1920 census, there were 32 different nationalities that were registered in the census. They had all come to work in the coal mines. A lot of those people came here, and they stayed here, and then they made their livelihoods, their families, their homes here.

This place is very white [she laughs], but there are people here that come here and live here and choose to stay here and are welcome here. I mean, of course this place has its issues, but we’re not all backward.

Pier Carlo: And there’s a place for queer people there too?

Lacy: Yes. “No Hate in My Holler.” That’s one of the biggest pieces that I’ve made. That’s one of my proudest pieces that I’ve made.

Pier Carlo: Talk about how you came up with the idea and then disseminated it.

Lacy: “No Hate in My Holler” came about in 2017. We got word that a group of neo-Nazis were coming to Pikeville, KY, which is about an hour from here, to try to recruit. It was under the guise of, you know, white families needing to band together to save America or whatever. It was obvious what it was.

I was working with the Appalachian Media Institute at the time at Appalshop. I was doing some work for them, and we had a youth drop-in center. One of the youth suggested doing an art-and-response day to that, and we all thought that was an amazing idea. So the night before, I was just trying to think of what I could make for the next day as some piece of protest. A hollow or a holler, which is what most people call a hollow is a ... because the mountains here, there’s usually a creek in valleys between our mountains, and so a lot of people live between the mountains. The holler is where a lot of people live, if they don’t live in town, and so it just popped in my head: “No Hate in My Holler.”

Some of my best ideas happen just if I’m taking a shower, if I’m not actually trying to dwell on what I’m trying to do, if I’m doing something else. I like to let my mind wander. I had it in the back of my head that I was trying to figure something out, so I was doing something, and that saying just popped in my head, and I was like, “OK, that actually is really cool.”

I do a lot of block-printing, and so the next day during our art-and-response day, I carved this piece and printed it and posted it to my Facebook page. It really caught on, and from there, it has really grown. I print my own shirts, and I’ve got stickers. It’s gone up on billboards in three or four different towns in the region.

Pier Carlo: Was it displayed in Pikeville where the neo-Nazis were gathering?

Lacy: Yeah, it was. It was.

Pier Carlo: Wow.

Lacy: I always donate at least 25% of the profits from the merchandise I make, so I’ve gotten to donate over $7,000 to different nonprofits working toward equity and equality in central Appalachia since 2017. It’s probably the piece that I’m most proud of and I’m most well known for.

Pier Carlo: In your community, as opposed to some of your other art, that could have been seen as almost political. Was there any kind of pushback in your community?

Lacy: I’ve not received any, I mean, not to my face. When the billboard went up in Pikeville with it on there and one of the local news stations came out and did a story on it, people were like, “Don’t read the comments.” And I was like, “I won’t. I never do.” [She laughs.]

Pier Carlo: And then you also decided to create a non-profit yourself, right? EpiCenter Arts. What made you want to start the organization?

Lacy: EpiCenter Arts was formed in 2014. I’ll bring up Appalshop again because I really do feel because Appalshop is here, there have been so many opportunities. That’s one reason, I think, that being an artist here has been viable in a way for me because it has led to so many opportunities and networking opportunities. In 2014, Appalshop were wanting to form some studio spaces. They had a building, and they wanted to see what artists needed. We had several meetings, and some of the artists in the area came to those meetings to give their opinion, but those studio spaces didn’t come to fruition. But we decided that we should keep meeting because an artist’s life can be kind of a lonely life and there was nothing here that kept artists together and talking. If you’re in your studio working all day [laughing], you don’t see a whole lot of people, so we wanted to make a place for ourselves.

And so myself and three or four other artists co-founded EpiCenter, and we started having critiques of each other’s work. We would just get together and kind of see how we could help each other out. We’d see if there were different supplies that we could share, because there’s no art stores around here; you’re going to have to order supplies if you need them. We were trying to share opportunities in those ways or share grant opportunities that we came across, things that we thought other people might need.

Then we started thinking about, “Well, what can we do in the community? Is there a way that we can offer art classes?” We got a couple grants, and we did some community workshops, which were really great. We actually raised money and sent one art student to, I believe it was Germany, to take some art classes there.

Pier Carlo: No kidding!

Lacy: It’s been a few years, but we were really pretty proud of that because she was straight out of high school. I think she ended up going to either Harvard or Yale, I can’t remember exactly. She was obviously very talented, and we wanted to help support her somehow, so we helped raise money to send her for that opportunity.

Then we ended up applying for a Rauschenberg Foundation grant, and we were one of the first two Appalachian arts organizations that got this grant funding. It was a SEED grant. We were really proud of that.

Pier Carlo: What did that grant support?

Lacy: That supported a director. At the time I was coordinating for free [she laughs] and trying to do, you know, the life of an artist, doing what I can just to make things happen.

Pier Carlo: I want to talk about that. At a certain point you realized, “Wait, hold on, I’m an artist; I don’t want to be the director. Let’s figure out a way to hire somebody.”

Lacy: Yes, exactly. Yes. That was my thinking.

Pier Carlo: How long did it take you to come to this decision?

Lacy: Maybe two or three years, I think.

And then the studio I’m sitting in right now, EpiCenter rented this space as a gallery space, and we were going to have a workshop in this space. We rented it right before COVID hit, and then COVID hit and then we didn’t get to really turn it into anything. I was using the space to work on murals in the workshop room and we just so happened to have it available. There were some international curators that were coming through in September. Because I lost my studio space and my husband lost his record store because of the flood and with those curators coming through, it lit a fire under us to try to get —

Pier Carlo: What was bringing the curators through town?

Lacy: The International Curator Conference was going to be in the United States for the first time, and they were going to be in Louisville. I’ve gotten a couple grants through the Great Meadows Foundation, which is out of Louisville, so they were familiar with Whitesburg and my work and some of the other artists work down here. They wanted to show the curators a global idea of Appalachia, so they wanted to bring the curators here. There were a hundred international curators that showed up in Louisville, and 40 of them made the trip to Whitesburg.

Pier Carlo: That’s incredible!

Lacy: Yeah, it was really cool. There were some from Belgium, from Italy. There were several from America, from Miami and California and places like that.

Pier Carlo: I love that, because also I think every country has their version of an Appalachia, often a mountainous place with people who are misunderstood by the larger population who make up stories about it. So I love that first of all this first conference was held not in New York or L.A. but in Louisville, and that they came through Appalachia.

Lacy: Yeah, we were very excited. We knew about it since earlier this year in March, I think. A smaller committee of four of the curators, like the director and a couple of others, came through to see the space then. And then once the flood hit, we were like, “Well, that’s obviously not going to happen. They’re not going to bring anybody down here.” Then the cleanup happened, and it was available to them to come through, and we were very excited that they still wanted to come.

There were still places that were in renovation and cleanup. Even to this day, there’s still places that are working on that. But we got our studio, the gallery set up enough to where they could come and visit. Yeah, we were really excited, and they seemed to really enjoy themselves. There’s a place up on the hill in the old high school, within walking distance from where we are, called CANE Kitchen. It’s a community agricultural kitchen, and they got to go to a square dance there. And I mean, we had a big old time. We got to sit and eat and talk to each other and see more artwork up there. So yeah, it was really good. They seemed to really enjoy themselves.

Pier Carlo: The flood was really devastating for the area, and it sounds like it hit both you and your husband’s workplaces, right?

Lacy: Yeah, we were both self-employed. My studio was in the back of his store. I’ve had several traumatic incidents in my life, people passing away that I loved and things like that, but this was a different level of … . Even though our house was OK — we lived up on a hill — we were just losing our livelihoods.

And then also just seeing ... I’m going to try not to cry, but it’s hard to not … seeing other people, what they’ve lost, people that you know and loved. My cousin, her husband had to strap her and their baby and him to an electric pole outside their trailer to keep them from being swept away. There were stories like that that you were hearing every day. It was incredibly intense. Every day I would drive into town to try to clean up our store. There were just piles of debris from people’s houses, and then they’d clean it up, and then the next morning there’d be 10-foot-high piles of debris again. For three months. I mean, there’s still piles of debris. It’s like, when will this ever stop?

But I feel like people, at least a lot of the people that I talk to, feel like we’re on the upswing, and things are happening that are good. I mean, some guy walked in here the other day … because we have the gallery space in the front and my studio is in here, and then we also have the record store in this building as well.

Pier Carlo: So the record store moved into the same building too? That’s cool. So you and your husband are still working close to each other.

Lacy: Yeah, it’s like a little arts-and-music co-op now.

Some guy came in here and was looking around, he was like, “We’re never going to be able to recover from this.” And I was like, “I just don’t want to believe that.” A lot of people have moved away because they can’t rebuild. If their house was flooded and they did the FEMA buyout, where FEMA buys their land and that means the county actually will own their land, that means that nothing can ever be built on that property again. So where do they go? I think FEMA can only pay $33,000 or something. I think that’s the limit. You can’t build a house for that, so where do these people go? Where are they going to go? Where are they going to live? I know a lot of people have had to move away. We already had an issue here of population decline and our young people moving out. But I really want us to come out of this better if we can.

Pier Carlo: Can you talk about that? In your dream of dreams, what does that look like, you and your fellow artists coming out of this better?

Lacy: Well, we’ve been scheming some public art pieces that we want to do, but one of my artist friends was like, “We have to come out better than we went into this.” And I was like, “Yes, I agree.” So how do we do that? How do we make this happen?

I think artists need to be involved. I just think artists should be involved in every level if they can in community planning and stuff. We’ve looked for ways to be included in workshops, and we want to do public art pieces. There’s a guy that lives here in town who’s known as the Post-It Picasso. He does little Post-It murals in the windows. After the flood he did Muppets and stuff to brighten up the windows for the kids. Any small thing, I think, that our artists can do in that way, I think that’s beneficial. Those are the little projects that we’ve looked for, if we can somehow be involved.

I don’t know how many people have thanked us for opening this location up, just because it makes them feel like we’re coming out of this. Because an art gallery, working artist studios, the record store’s back open … it gives people a sense that there’s some optimism here. Things are growing, and it’s not shutting down.

Pier Carlo: You didn’t move away.

Lacy: Right, exactly. And that’s one thing we posted on our social media right after the flood happened: “We are not leaving. This is our home.” I’m going to start crying. [She speaks through tears] Growing up here, we wouldn’t leave it. When we were cleaning our store out down there … . I did a lot of my screen-printing down there; I did a lot of my block-printing down there. I’d just finished hand-printing 215 cards for a project with Silas House. He’s an author, a Kentucky author. They were going to go out with some of his books, and here was all of this, just scattered all over the store and just flooded in this toxic gross-smelling mud.

Some of my friends and one of my fellow artists were there to help me every day, which I will never be able to thank them enough. But there were strangers, complete strangers off the street that would just come in and just get down on their elbows and knees and be pulling carpet just to help us. Every day I’d start the day in tears and so grateful for these folks and then have to jump in and throw out so much of what we worked so hard for.

Coming back to community, there’s no way we could have gotten through that and opened back up and been in this space if I hadn’t been for the community. That’s another reason that we wanted to make sure that people knew that we would not leave. That’s another reason that I want to be here to make projects that our communities are proud of and that will uplift the people here. Because this is a poor area. And I grew up really poor. Sorry to get so emotional.

Pier Carlo: No worries.

Lacy: It’s been a very trying time for several months, but I really feel like art is very healing. After the flood happened, I made a piece — it was just really a drawing — and it was of a woman standing in front of the mountains, and her hair came out and turned into ... . I couldn’t do any artwork for two months probably because I was still processing everything, but I knew I wanted to. For a little while I would look at my jewelry on my nightstand and be like, “I can’t even wear that. Is this even … ?” Everything seemed so trivial. Art to me, I was like, “I don’t know if I’ll be able to get back to that.” I mean, it just seemed so ... . People’s lives were so upended, and ours were too.

But after a couple months I was like, “I’ve got to make something.” I just felt like it was necessary, and so I made this piece. It was a drawing of this woman standing, almost floating, in front of mountains and her hair is flowing out, and it kind of rolls into the mountains. It turns into the mountains. And she’s holding the state flower, which is the goldenrod, in one arm and a dulcimer, which is a traditional Eastern Kentucky mountain string instrument. I don’t know if you’re familiar with the dulcimer, but it’s a lap instrument, a stringed instrument. At the top, it says “Eastern Kentucky,” and at the bottom it says, “Resilient, strong, dignified, here.”

Because I saw articles, I saw comments being made, like, “Well, why don’t they just move out of the flood plain? I don’t get it.” It’s not that easy. People can’t always do that. And a lot of these places weren’t even technically in the flood plain; a lot of these places did not flood. Never in my mind would I have imagined that flood would’ve gotten up into the location where my studio was. The river that was next to our building was usually two feet deep. The river crested that day at over 20 feet.

Pier Carlo: You mentioned combating population decline. What do you think would make it easier for an artist such as you to really commit to living and working in the town where they grew up or in any rural town that they want to live in?

Lacy: I think, for one, art education is something. I’ve been thankful that recently more schools have been asking me to come do career days. I actually just did a career day a couple days ago. Students come up to me and are like, “Wait, you’re an artist.” And I’m like, “Yeah, yes, I am full-time.” [She laughs.] And they’re like, “How? I don’t understand.” And so I get to talk to them about that. People don’t understand. They don’t realize that that’s a possibility.

Pier Carlo: I have to say, one thing that struck me about your community pooling together to send you to Pratt was they weren’t sending a promising student to become a lawyer or a doctor. They were sending you to become the artist you were meant to be. That’s very moving to me.

Lacy: Yeah. Well, yeah. And you can see it right there. It explains it, right? That’s why I do what I do.

December 19, 2022