Maura Brewer

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Early in her career, video essayist and performance artist Maura Brewer explored the relationship between representations of women in Hollywood films and the structures of contemporary capitalism. Through several often-tongue-in-cheek video pieces, she focused on the actor Jessica Chastain, who at the time was being typecast in films such as “Zero Dark Thirty” as a steely go-getter who paid a steep personal price for her ambition.

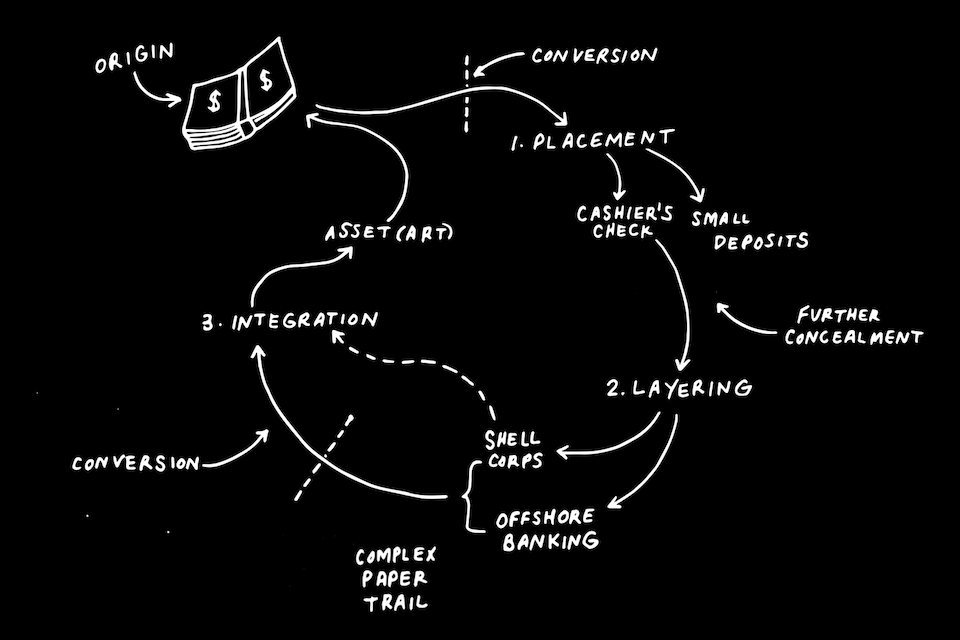

In recent years, Maura’s focus has shifted from representations created by capitalism to the underlying financial structures that uphold it. To wit, she is deep into a years-long project titled “Private Client Services” that explores how the rich launder money through art acquisition and sales. In this project, which Maura is documenting meticulously through video and writing, she herself is doing the very thing she is studying, namely laundering money through art.

Maura is not entering this world entirely dewy-eyed, however. For several years, in addition to being an artist, she has worked as an experienced professional private investigator, garnering skills that are proving invaluable in her forays into the world of money laundering.

Her work has been exhibited at spaces including MoMA and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Chicago and is in the collection of the Los Angeles County Museum of Art. Her projects have appeared in The Guardian, CBS News and The Paris Review. She is a 2023 Guggenheim fellow, a 2022 Creative Capital fellow, and a recipient of the Fellowship for Visual Artists at the California Community Foundation and the City of Los Angeles Master Artist Fellowship.

In this interview, she details how she, once a fiber artist, harnessed her own investigative talents to create performance and video art about a crime that uses art as its primary instrument.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- How did you develop your voice and vision as an artist?

- How did you get into the P.I. work? Was it purely out of economic necessity or was it related to your artmaking?

- How has that work influenced your artmaking, and how has your artistic spirit informed the P.I. work?

- Tell me how you homed in on what you wanted to do with this project and the steps that it took to create it.

- Why is art so useful to rich people for reasons other than aesthetics or its intrinsic value?

- Are there crooked appraisers who actually set the value on a piece of work before it's sold?

- When will you know that that “Private Client Services” is completed?

- When you picture the project as being completed, how is it going to be presented to viewers?

- How has all this research into money and art affected your own understanding of money and of the value of your own art?

- Given what you've learned about these rigged systems that rarely benefit the artists, what tools can artists arm themselves with to give them more leverage, more power?

- How is the new ease in your life that money is affording you affecting the way you move through the world?

- Do you have any idea of what you might be diving into next? Is there another interest that's starting to gel in your brain?

Pier Carlo Talenti: How did you develop your voice and vision as an artist?

Maura Brewer: I went to the School of the Art Institute of Chicago for undergrad. When I was really young and kind of trying to figure it out, I was making soft sculpture. I came through the Fiber and Material Studies program at the Art Institute.

It’s an interesting school where you don't have a major and can kind of do whatever you want, so I ended up working closely with a video artist named Vanalyne Green, who's an amazing feminist video essayist. I was very interested in quilting and found materials and feminist histories, and I started to get more interested in working in a less abstract way. I was always reading and writing, and I was interested in putting that energy into my work. It felt like video, especially appropriative techniques and video … .

My videos combine footage from YouTube and movies and text messages and all kinds of things. I think that those feminist histories, where you're combining a bunch of different found materials — which comes out of this waste-not-want-not ethos — became a kind of funny, natural fit for me to move from a fiber practice into video.

Even though those things sound far apart, I don't think they are that far apart at their heart. They're both collage practice. A lot of times I think of my video as just working with a lot of found garbage — like bad movies, clips from video games, weird footage that people have shot on the internet — and then recombining that stuff. It's recycling.

A lot of times I think of my video as just working with a lot of found garbage — like bad movies, clips from video games, weird footage that people have shot on the internet — and then recombining that stuff. It's recycling.

Pier Carlo: I'd never heard the phrase "waste not, want not" applied to video. Does it mean, why spend energy creating something new when there's plenty of existing material to recreate into something new?

Maura: Yeah! Well, and also to be straightforward, I was and still am most of the time kind of broke. I'm less broke now than I was, but I was very broke as a young artist. There's a political economy but then there's also just an economy to how you are going to make your work. Video, digital media, is amazing because you have your computer and that's basically all you need. You can remix a universe of endless materials.

Pier Carlo: So how in the course of your artistic career did you get into the P.I. work? Was it purely out of economic necessity or was it related to your artmaking?

Maura: Yeah, it was very surprising. I taught as a college adjunct for 10 years. In later years, I’ve been told that this is just kind of how people get into this industry, but as I alluded to, I was starting to make video work where I taught myself how to pull public records because I was doing this Jessica Manafort work. I would read about her divorce, and then I'd be like, “Oh, let's find the divorce and use the real document in the video.”

One of my employers is sort of sometimes in the art world himself. The private investigation industry is full of interesting people. We had a mutual friend, and he came across my work and basically was like, "Oh, you're already doing this, but I can train you to do a better job." [She laughs.] So then I started working for him part-time for a couple years, and then he was like, "You're not going to really learn unless you do this full-time." So then I left teaching and have been doing the P.I. work full-time for the last two years.

It's been a really excellent, really amazing training. You don't really go to school for it, so it's on-the-job training; it's more like apprenticeship. It's been challenging and interesting.

Pier Carlo: What types of cases constitute most of your work?

Maura: It's really all over the map. We're a small firm, and we do all kinds of things. We do work for documentary filmmakers. We’re based in Los Angeles so there's a little bit of that kind of work. We also do a lot of litigation research, so people who are being sued or going to sue someone else. We might work for lawyers to background people who may be deposed, for example.

I've been very involved in a political-opposition case, which I'm really super into. We do some political-opposition research, which is like we're working for a political organization to research their adversary.

Pier Carlo: So you're digging up dirt on the adversary. There's movies about this stuff!

Maura: [Laughing] There’s a lot of people doing that kind of work out there in the world.

Pier Carlo: How has that work influenced your artmaking, and how has your artistic spirit informed the P.I. work?

Maura: It's been fantastic actually. It's been a really great back-and-forth connection. The work I’ve been doing for the last couple years is all about money laundering, and in order to do that work, I've been learning how to launder money. Part of what I'm interested in is, what are the corporate mechanisms for laundering money? So how could you create a corporate architecture across multiple jurisdictions, and how do you make that architecture anonymous? How do you shield yourself?

The P.I. work has been very useful in terms of understanding how to read corporate records and financial documents of all kinds. There's a world of information that I didn't know existed that's all on the public record.

Pier Carlo: You have to know how to read it, though, because shell companies are all about shielding identities and creating layers of obfuscation.

Maura: Yeah, and it's interesting what you can find and what you can't find. Delaware, for example, really is kind of a black box. There's a reason that people talk about Delaware. It's very hard to get information about companies that are formed in Delaware. Even with onsite research, we can get some things, but there's a real limit to it, so it's been interesting just to learn that stuff firsthand.

Pier Carlo: Tell me how you homed in on what you wanted to do with this project and the steps that it took to create it.

Maura: That work came pretty directly out of this work that I've mentioned a couple times where I made a couple videos about Jessica Manafort, who's Paul Manafort's daughter. She is a filmmaker in Los Angeles. She's made two feature-length films. I got interested in her because, well, I was just kind of reading about Paul Manafort. There was a very long, really excellent profile of him in The Atlantic several years ago. He's this really interesting character, sort of a minor political figure in a lot of ways but he's been in the middle of all kinds of the worst shit for his entire career.

Halfway through this article, there's a little aside that one of his daughters is a filmmaker and that he's funded her work. I got just really curious, because he was being indicted for money laundering. I was wondering, well, if he was funding her work and the work was happening around the same time that he was involved in all these criminal activities, then could her films have been a vehicle for money laundering?

And if that was the case, the thing I was really curious about is sort of a silly question, which is, is there an aesthetics of money laundering? Could you watch her films and in some way do a close reading of them that might reveal their material origin? Which is a kind of impossible idea, and of course, I didn't have any proof one way or the other. I couldn't really come to any conclusions about whether or not the films are vehicles for money laundering, but I did my best to reconsider them through that lens.

Then I made these two videos about her two films. Then I was thinking: “Well, this is great, and it's been interesting, but in some ways this is all a kind of displacement. Because I don't have to look at film to think about money laundering. Money laundering is happening in the art world all the time. I'm an artist, and so why don't I just see if I can launder money myself through art acquisition instead of looking at the way somebody else might do it through film?” So then I thought, “Well, I'll do this performance where I try to launder money through art acquisition.” And that's “Private Client Services.” And then I'll make a video about it.

Pier Carlo: So first you need to get the money to launder, right?

Maura: Right.

Pier Carlo: Where did you get money to launder?

Maura: [She pauses and laughs.] No comment.

Pier Carlo: Nice!

Maura: Well, seriously though, people always ask me that question, and of course it's the most interesting question, so I have to refuse to answer it. But the thing that I'm really interested in is, money laundering is a crime that happens after a crime. It's like the second crime, and it's the boring crime. Whatever the first crime is, is interesting; the second crime is boring. It's about accountants and paperwork and corporations and moving money from one place to another. So I decided that it would be in the work’s best interest — and probably in my own best interest — to not talk about where does the money come from but rather to talk about where does the money go.

Also the more I work on this project and understand the financial landscape of the very wealthy, as much as I could understand it, the thing that ... . Money laundering is a flashy word, and it is definitely a problem in the art market, a big problem. There was a Senate investigation about it recently. The more I research this world, the thing that I find myself actually interested in is tax evasion, which is more boring and maybe doesn't get you as many grants, but it uses a lot of the exact same financial mechanisms as money laundering. And oftentimes it's technically legal in the ways that it's done. Maybe not tax evasion but tax avoidance is a kind of huge pastime of the rich, and they use art to avoid taxes all the time.

Pier Carlo: So why is art so useful to rich people for reasons other than aesthetics or its intrinsic value?

Maura: think the question of intrinsic value gets to the heart of why it's interesting, why it's useful, because art really doesn't have intrinsic value. Or if it does, who the hell knows what it is, right? Art is so incredibly speculative. Prices are extremely fungible. Art is purely worth whatever we say it's worth. Whatever the market will bear is what it's worth.

I was recently reading a paper about fraud in the art world, and it was looking at Inigo Philbrick, who's a famous art fraudster. It was this great research paper that was really laying out what his scams were. He was convicted; he's in prison right now. Basically, a lot of his scams revolved around this one Basquiat painting that he sold and then resold and then resold to different people for varying amounts over and over again. He would sell it to one person and then go turn around and sell it to someone else, not having told them that it had already been sold. He would sell it to one person for like $12 million and then turn around and sell it to another person for $22 million, all in the same month.

Pier Carlo: Wow.

Maura: There's no way that Basquiat painting is worth double in a month period. But then what is it worth? It's worth whatever the person believes it's worth. So as a vehicle for speculation, art is really excellent.

Pier Carlo: So are there crooked appraisers who actually set the value on a piece of work before it's sold?

Maura: Yeah, there are e definitely appraisers. I don't know. I don't want to accuse any appraisers of being crooked, particularly. I don't know what is going on with that. My feeling is that a lot of times these are just social relationships. You’re at a party, and your buddy says, “This is a great investment.”

For “Private Client Services,” one of the people I've been talking to is this really wonderful person who's in pretty high-end art finance, and he's very philosophical about this. What he says, which I think is really true, is for the very, very rich, art is wonderful because a lot of those people really like art. It's beautiful. It's aesthetic. Also you get to go to great parties. The social scene is cool. What it is is a high-end collectible. Then as a special bonus, you also get to maybe make a bunch of money. So it's a little bit of everything.

The social world runs on fictions, like, "Oh, my friend, I'm getting this amazing deal.” If people believe it, then it happens.

Still from “Private Client Services,” 2021-present, video, performance, sound

Pier Carlo: Is “Private Client Services” completed?

Maura: No, it's not.

Pier Carlo: OK, so at what point are you in it? And when will you know that it's completed?

Maura: I made a version of it, and I thought it was completed. Then as it turns out, the art world really wants me to continue laundering money. [She laughs.] The art world loves money laundering. So I proposed an extended version of the project, and then I've been lucky enough to get all this funding for it, which is why I really can't say that I'm broke anymore.

The first version I did through a Shell corporation in Wyoming.

The art world really wants me to continue laundering money. The art world loves money laundering. So I proposed an extended version of the project, and then I've been lucky enough to get all this funding for it, which is why I really can't say that I'm broke anymore.

Pier Carlo: Which is the new Delaware, I understand, right?

Maura: That's what I was told, so I thought I'd check it out. I found a very good service that made a corporation for me. It was very easy. For this version, I'm doing a more complex version in which I'm making a corporate structure across multiple international jurisdictions. I'm working with a lawyer who’s advised me as to which jurisdictions would be most amenable to both art acquisition and money laundering. And then I'm visiting each of those locations.

Pier Carlo: I want to guess. Can I guess?

Maura: Please, yeah!

Pier Carlo: Monaco.

Maura: Close.

Pier Carlo: Malta?

Maura: No.

Pier Carlo: It's not France. It's not Italy, is it?

Maura: No, but also close.

Pier Carlo: [Laughing] Can you reveal where you'll be traveling?

Maura: Yes, yes. I'm going to Luxembourg. I feel like Luxembourg is close to Monaco in spirit. Luxembourg, Switzerland, Hong Kong, the Cayman Islands, where I've already been. I went to that one. And then I think I'm going to Malaysia as well. There's a finance center that's kind of new in Malaysia on an island called Labuan.

Pier Carlo: Oh my god, Maura, listen to you! You're living the life of this high-flying money launderer. Did you ever think this would be your life?

Maura: No, but I'm very amused by it. [She laughs.] It does feel like kind of the best joke I've ever thought of. I'm very, very pleased.

Pier Carlo: When you picture the project as being completed, how is it going to be presented to viewers?

Maura: I'm making a video that's kind of a travel video. It's actually an installation. That'll be part of it. And then I think I'm also going to be producing a publication in conjunction with this lawyer that I've been working with. It'll be a guide to money laundering in the art world.

Pier Carlo: Considering that you said that until recently you were pretty broke, how has all this research into money and art affected your own understanding of money and of the value of your own art?

Maura: I think most artists have a complicated relationship to money. One thing I'll say is that I do think that I became interested in this work because I want money. There's a certain amount of desire that's real for me. I think hopefully that'll be part of the work because I think that that's important to think about and address. I think one of the things that I'm interested in is thinking about the of gap between … .

This is the thing that I really loved about teaching when I was teaching at an art school college. I would go to my students’ studios — they're undergrads and young — and a lot of times they're just making their thing, and they're doing something that's pretty crazy or whatever. It's just something and they're doing it, and they can't really always tell you exactly why they're doing it, but they need to do it. They need to do that thing.

I just always thought that was so incredibly moving, really beautiful, the drive that humans have to create things. I do think that creativity is a fundamental human need, and I know that it has been in my own life. I think that when you are driven by something that isn't primarily monetary in our culture, you are taken advantage of. It becomes very, very easy to be exploited because there's somebody who will figure out how to make money on what you're doing.

I've always been a working artist but always had a variety of day jobs and student loans and all that stuff. I also really committed to video art, which does not have a huge market application. There are not many video collectors in the world. And that's not really the history of video I was ever interested in. I like the kind of video that you can just watch on the internet. Thinking about my path and how tricky it's been for me, I've been very lucky, but I've had to work really hard to be able to make the kind of work that I want to make with any kind of sense of freedom.

Then thinking about my students who were paying double what I was paying to go to school and really saddled, crippled with debt in a way that I couldn't even totally understand, I was just thinking, “Well, what kind of world are we making? Are there going to be video artists and performance artists anymore? Is there room for a making or creativity or expression that is not driven by the market?”

Then the flip side of that is that artists who make work that does have market application, who maybe show in commercial galleries, you make your work in your studio and it has one kind of life and existence for you, and then it goes out into the world and has a radically different kind of existence as a financial vehicle.

Pier Carlo: From which the original artist rarely benefits, right?

Maura: Yeah, absolutely. Often that can become a very precarious situation. All of a sudden, you might be a young artist and you become a kind of thing for a minute and your prices go up, but then the market can't sustain that, so then your prices go down. Then you can't recover from that. That's a really common story in the art world. The thing that you made, which is sustaining you intellectually and emotionally, is also part of this larger system, which is structurally oppressing you.

What I want to do is close the gap, bring together the experience of being a working artist in the studio with then how does this artwork function within the larger sort of economy and bring those experiences closer together.

Pier Carlo: So how can artists resist being the oppressed ones? Given what you've learned about these rigged systems that rarely benefit the artists, what tools can artists arm themselves with to give them more leverage, more power?

Maura: [She laughs.] I do have an answer for that question. I will say I don't really think of my work as activist. I've been telling people that my work is … you could think of it as landscape painting, except the landscape is financial, like the art market or something.

Pier Carlo: And I hope I wasn't... Yeah, I totally understand that. I'm just asking because you are more educated about this world than most people. So aside from your art, I'm just asking about your opinion, I guess.

Maura: Yeah, and I guess my opinion is that — I’m a socialist — I don't think that there's any way to operate within capitalism without both perpetuating capitalism and also perpetuating your own exploitation within capitalism. I don't think there's any space of purity. If I'm being practical, I think everybody has to just figure out how to survive.

The things that I believe in and that I think we should be demanding is a return to government funding for the arts. One of the grants I received recently, Creative Capital, was explicitly created in the wake of the government ending NEA funding for visual artists because the federal government took that away when they decided that visual artists were too controversial to receive funding. Since then, there's been a kind of terrible vacuum.

If you go back and look at the WPA, the social programs of the early 20th century, some of the most iconic American art was being made through those programs where the federal government was directly paying artists to make work. I think that that is a huge value to society, and it should come back.

Pier Carlo: Right, work that still beautifies so many of our spaces today.

Maura: Yeah, incredibly important work that has intrinsic value and that I think should be publicly supported, not supported through private nonprofits or private charity but supported through the government directly. I think that's incredibly important.

I also think that artists should demand real reforms within the education system. I don't think artists should be paying $90,000 a year to get bachelor's degrees with no job applicability. Up until very recently, that was not how the world worked. My mom is an artist. She went to art school at PNCA [Pacific Northwest College of Art] back in the day, and she had no student loans because she was able to work a job and pay her tuition.

Pier Carlo: I'm sure you will address this in the work, so I'm jumping the gun a little bit, but how is the new ease in your life that money is affording you affecting the way you move through the world? I'm just curious about what new insights it has given you about your own relationship to money.

Maura: [Laughing] Yeah, I've tried to adjust to it. I'm such a naturally pissed-off person and I'm trying to ... . It is very funny to me that the thing that gives me funding is that I tell everyone I'm going to launder money. That's the way you do it. That's the way you get money is by laundering money. The irony of that is really amusing to me.

In terms of my own life, I'm trying to mellow out a little bit and, I think, make work about the things that I care about. Of course, I'm going to have passion about that. But yeah, I'm kind of trying to adjust to the idea that maybe I don't have to work quite so hard. It's a weird adjustment.

Pier Carlo: Are you still doing the private investigative work, or do you not have time for that or need for that?

Maura: Oh no, I'm doing that. I'm doing that. I always have lots of jobs, but I really enjoy that work. I'm just doing it a little bit less to have more time for my practice, which is an incredible luxury to even be able to say those words.

Pier Carlo: I know “Private Client Services” is first and foremost on your mind, but do you have any idea of what you might be diving into next? Is there another interest that's starting to gel in your brain?

Maura: Yeah. Always. [She laughs.] I always have a long list of things I'd like to be working on. Some of them are bad ideas, and so we'll figure that out, but some of them might stick.

I am interested in making a piece about the private-investigations industry. I'm particularly interested in public knowledge and private knowledge. I'm interested in non-disclosure agreements, which I've signed as a P.I., and what the economy of information is in the world, so I have something kind of percolating about that that I'll probably get into more deeply when I'm done laundering money if I'll ever be allowed to stop laundering money.

June 14, 2023