Narsiso Martinez

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

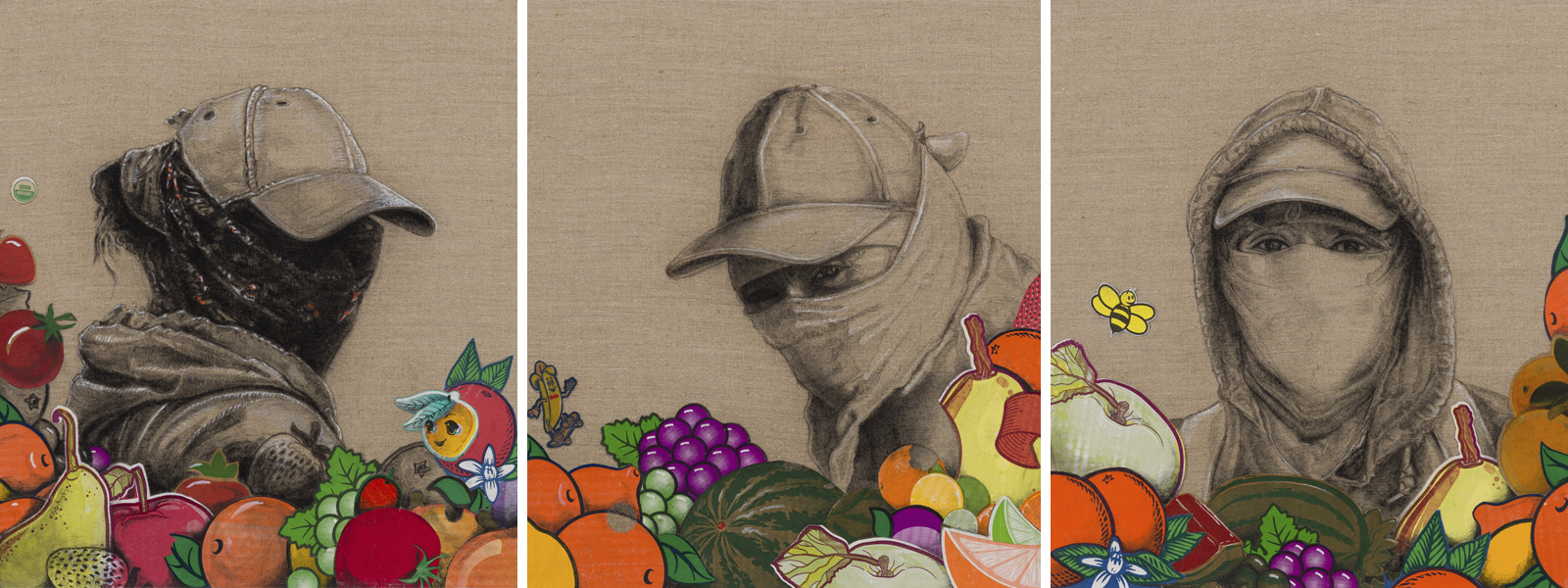

Narsiso Martinez creates drawings and mixed-media installations that focus on the lives and labor of the thousands of migrant agricultural workers on whom we all depend for our produce. Not only are the detail and atmosphere of each of his pieces breathtaking, but his canvas, so to speak, is also remarkable and evocative. He creates and assembles his work on and with discarded cardboard produce boxes that he himself collects from grocery stores.

He knows his subject well as he himself earned money to pay for his art education by working alongside friends and family in the agricultural fields of Washington State.

Often his work is monumental in size. In fact for most of April 2021 a large piece of his was featured on a billboard in West Hollywood, CA, part of the non-profit Billboard Creative’s annual exhibition throughout the Los Angeles City basin.

In this interview with Rob Kramer and Pier Carlo Talenti, Narsiso reveals how tenaciously he pursued his dream of becoming a working artist and how having achieved that goal he is working to help others achieve theirs.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- Could you tell us about what projects are keeping you busy these days?

- I’m wondering if you can talk about what effect the last 14 months have had both on your own artistic practice and on your artistic mission as a whole. Could you talk about what the last year has meant to you artistically and in terms of your activism?

- A lot of our listeners probably aren’t as familiar with the daily life of being a farmworker, in particular an immigrant farm worker. What were your impressions of what life was like for these folks during this year of COVID?

- I think one of your missions is to communicate the farmworkers’ experience to people who may not know about them. I wonder what effect do you want your work to have on the farmworkers themselves?

- Are there goals that you have in terms of the societal changes you’re trying to achieve with your art?

- You’re creating and building an art center. What have you learned about yourself through this new process?

- You worked in the fields to pay for your education, earning your master’s in your thirties. Where did you get that tenacity?

- Do you have an artistic goal that you think you’re trying to reach, whether in terms of the reach of your work or an aesthetic goal you’re trying to reach?

Rob Kramer: Could you tell us about what projects are keeping you busy these days?

Narsiso Martinez: I’m currently working on different projects right now, and I think I’m going to start with the most recent. I am currently working on a project that involves an organization in Wenatchee, WA. It was supposed to be an artist in residence, but because of COVID it had to be adjusted a little. I was supposed to go there and work with the community and do a mural, but instead we changed it to interviews through the internet and exchange of images. Now I’m working with portraits of people who are involved in the community with this particular project, which is renovating a park for the community. The park is called Parque Padrinos, and it’s in the city of Wenatchee in Washington State.

And the other project that is close to happening is “Cultural Undertow,” which is an exhibition that I curated through Luna Anaïs Gallery, and it’s happening at Tin Flats Gallery here in L.A. It’s a show about two female artists of minority groups, Tidawhitney Lek, whose background is Cambodian, and Gloria Sánchez, whose background is Native American and Filipino and partly Mexican.

The other project is my solo show at Charlie James Gallery here in L.A., the gallery I’m working with. It opens sometime in October.

And the other project is taking place in Fresno, CA. It’s organized by Arte Américas. I am from Oaxaca, Mexico, and it involves an exhibition about Oaxacans in the Central Valley. So I’m looking forward to it. That’s happening somewhere in early 2021.

Pier Carlo Talenti: Wow. [Laughing] You’re not busy at all!

I’m wondering if you can talk about what effect the last 14 months have had both on your own artistic practice and on your artistic mission as a whole. I know that COVID hit farmworkers disproportionately, and I know it’s a community that you paint and that you’ve worked with closely. Could you talk about what the last year has meant to you artistically and in terms of your activism?

Narsiso: Well, it’s been interesting. Actually, I had an exhibition last year sometime in March, my first solo exhibition at Charlie James Gallery, and because of COVID it couldn’t be open to the public. It was open, it was hanged and everything, but there was no reception. It was supposed to open to the public in March right when we took shelter-in-place thanks to COVID, so there was no opening reception. I didn’t see the show until months after. They decided to keep it hanged and open to the public months after by appointment only. That’s one of the biggest changes that happened.

Also personally I discovered that I need people around me. [He laughs.] At first I thought I was really tough, and I’d go, “Yeah, I love being in my studio on my own and just painting.” And that’s what happened for the few weeks at the beginning, but then after, I felt like I needed to go out and see people, to the point that I got — I was painting in my room at that time — to the point that I actually got a studio space somewhere else. And now I have a studio space.

And in terms of the farmworkers, I saw a lot of cheering through the internet to the farmworkers. I was excited to see that people were paying attention to the farmworkers, that they were being essential workers. I used to work in the fields, by the way, and I still keep in touch with a lot of my coworkers. I also have family members and some friends who work in fields. I was asking questions — How was it? How were they doing? — and it seemed like a lot of people were not wearing the proper protective equipment even in the middle of the pandemic when they were already deemed essentials. So that’s one of the things that was sad to learn about.

Rob: A lot of our listeners probably aren’t as familiar with the daily life of being a farmworker, in particular an immigrant farm worker. What were your impressions of what life was like for these folks during this year of COVID?

Narsiso: I think it was really, really risky, more than needed, I would say. I know farmworkers are treated differently in every state. Some states pay their farmworkers enough so they can sustain themselves, but in some other states their payments are really low and there’s no organizations that can support them, so it really differs, I’m beginning to understand.

I speak to people. I’ve spoken to some people now, and it seems like they’re economically doing OK, but I think they risk their health a lot. Even though it was on Monday that they would be provided the protective equipment that they needed, it seems like it was not really enforced. I can see that happening, because even without the virus going around, farmworkers who work in the fields are usually protected. When I was at least working in the fields, I wanted to protect myself from the pesticides and the weather conditions, either cold or hot. But it seems like when workers earn money by the contract, it’s really hard to breathe under those conditions when you have something on your mouth or your eyes. The glasses get foggy. And in order to make an extra buck, you just get rid of that. And no one seems to enforce that.

So that’s one of the major things that I learned throughout these months, that it was not really enforced, either because the managers pretend that they don’t see it or they didn’t actually see it. That’s the sad part.

Pier Carlo: I think one of your missions is to communicate the farmworkers’ experience to people who may not know about them. I wonder what effect do you want your work to have on the farmworkers themselves?

Narsiso: First, I want them to know that there are people out there paying attention to them. And not necessarily visual artists, like painters or drawings like I’m doing, but also moviemakers and writers like that, writing about them.

Specifically in my work, I want to pay homage to them; I want them to see themselves as worthy of being in art. I want them to be monumentalized. I want them to feel the work they’re doing is important.

Specifically in my work, I want to pay homage to them; I want them to see themselves as worthy of being in art. I want them to be monumentalized. I want them to feel the work they’re doing is important. I think those are the things that I want them to see.

I know it’s been a challenge for me to take the artwork to the farmworkers for them to actually see it, because of the media that I work with and also because of the nature of the career, which happens around an institution, like an art school. So it’s been a little bit of a challenge, but I’m working through it.

Pier Carlo: The material, meaning that the cardboard that you use is easily damaged. And they’re large works, so they’re hard to carry around.

Narsiso: Exactly, yeah. It’s very difficult to bring them to the fields. Or they would fade in the sun. Obviously the rain also is going to make them fade away or disintegrate.

But I’ve experimented a few times with vinyl printing, life-size vinyl printing. And I have taken a few to the community where I actually worked up in Washington State, and it seems to work. The pieces are still up. And it’s been like, what, more than one year since I took them over there.

Pier Carlo: Where are they up?

Narsiso: I took four pieces. I printed four life-size; two are six feet by nine feet, and the others are a little bit smaller than that. My idea was to go to the town — it’s a small town — and just go around to grocery stores and ask them if I could nail them to the wall outside so people can see it. But my brother who happens to be in that town was more ... I don’t want to say aggressive, but he had different ideas. That was my idea, because I was in a hurry and I was just going to be there for a week and come back. But he was more like, “No, I think we can take this to the City Hall and where more people can actually see it.” And I was, “OK, you’re in charge.” So I left the pieces.

We tried to go to the City Hall — we had to make an appointment obviously — and we spoke to people at the local library. I left the pieces, not knowing what was going to happen to them, but actually he was able to speak to the City Hall and got the City Hall to place them in a local park. And two other pieces went to the library. So it was pretty nice to see it. They shared pictures with me, and I actually went back and took some photographs later on. That’s one of the examples that were successful in bringing the art to the people.

Pier Carlo: Wow, that’s great. The lesson is to make your family your agent.

Narsiso: Yeah. My brother is a big fan now.

Rob: Are there goals that you have in terms of the societal changes you’re trying to achieve with your art?

Narsiso: Yeah, there’s a big project that I’m excited about. It started by a crazy dream, and it seems like it’s taking shape now little by little.

... it all started with the reason why I went into art, when I went to school and I learned about these artists who painted the peasant, the working class, like Van Gogh and Millet. I really wanted to paint scenes like that to preserve and to show the people that don’t know much about art or don’t have access to art.

It all started a long time ago when I was ... . Well, I feel it all started with the reason why I went into art, when I went to school and I learned about these artists who painted the peasant, the working class, like Van Gogh and Millet. I really wanted to paint scenes like that to preserve and to show the people that don’t know much about art or don’t have access to art.

Later on when I was in art school getting my master’s degree, I had this class where I had to create a [syllabus] for a class. I pretended I wanted a school that would teach art to the community, in communities that are far away from the cities, where they don’t have access to art classes or art itself.

Then I started looking around and looking at my own history and how is it that I learned about art, because I grew up liking art but not because I saw a lot of art around me. It’s just because, I don’t know, I had paper and pencils. Honestly I don’t even know how it all started really. I guess it all started because everyone as kids gets crayons and paper and we’re encouraged to do drawings but not really learning that art can be more than that. So that was one of the goals that I set on my head. When I had the opportunity to start this, I was like, “What if I go to a greater scale? What if I create a space where people can come and learn about art?”

With this idea in mind and with a little money I have saved, I started a project. I decided to start it back in my community in Oaxaca, not necessarily to get away from the United States but to have a collaboration between these two places that I have lived in now, half of my life here and half my life over there. And because I know people now through art school or through their community, through the art world, people from different kinds of life, from different parts of the world really. And now this project has grown to be an artist-in-residence, based on my experiences of doing a residency in Miami at the Fountainhead Residency, doing a residency at the Long Beach Museum of Art and at the Long Beach City College. It seems like that’s a good way to connect with people and to collaborate.

So that’s how I’m picturing it in my head. And that’s the goal. That’s the goal. It keeps changing and growing as it’s taking shape.

Pier Carlo: So you’ve already created a residency for an artist in Oaxaca?

Narsiso: I’m starting to. I’m starting. It’s not like it’s a done thing yet, but it’s starting to take shape. I’m in the early stages, I would say. I’ve been working on this in my head for a year. Finally, we have some progress. I should say what the progress is, that we got the land, we got the materials to construct and we have the people who are interested in being involved in this project. We’ll see where we’re at next year.

Pier Carlo: Wow, so you’re actually creating and building an art center! That’s a big deal. Are you enjoying it? What have you learned about yourself through this new process?

Narsiso: One of the essentials that I’m going to need for that, like, am I going to need to leave my practice, my drawing and painting practice, to actually lead this thing? Or am I going to be involved with something else? How are we going to communicate? This is a big question mark. I’ve been thinking about this, and one of the biggest challenges is the language barrier basically. I know now by looking around that there is a school in Oaxaca that specializes in different languages, so I could collaborate with them and have some translators whenever there’s an artist in residence. Because the idea is to have some kind of exchange between an artist who can come and do work in the community but also teach a class or two to the community.

Pier Carlo: You worked in the fields to pay for your education, earning your master’s in your thirties. Where did you get that tenacity?

Narsiso: I think I really wanted to break the cycle. At one point I understood that I couldn’t do well in school back in Oaxaca because of so many disadvantages. Growing up, you worry about other things like — I don’t know if I want to get too personal — but just growing up and not having enough to eat. Or “I have to go to the fields and take care of the cows when I get home.” Or “I don’t want to go to school because I don’t have shoes.” Or “My pants are too torn apart that it’s embarrassing to go to school.” Worrying things like that, I’m assuming, didn’t let me focus in school.

And the fact that Indigenous people in Oaxaca were really discriminated against. I remember going to the cities with my parents and people were just looking at us weird. It was so strange, no? And my family wanted to assimilate in the city by not encouraging us to speak their Zapotecan language or dress in certain ways. And I didn’t like any of that.

Also the Church didn’t help us much by encouraging people to just be within their thoughts of everything is destiny. Everything is preordained; you cannot do more than what you already doing. That’s the way it’s supposed to be because someone said so. That mentality I want to change.

Eventually I understood that I could, once I got to the United States and learned from my teachers here in school when I was taking the ESL classes and they were like, “Yeah, you can do this, and you can do more if you want.” And at one point I was like, “OK, yeah, these people are not liars. They couldn’t be liars.” I think I believed them, so I worked really hard. And I really wanted to break the cycle.

At one point I made it my goal. And when you have a goal, you either meet those goals or die working towards those goals, and you die happily.

Pier Carlo: Would you say you’ve reached your goal then?

Narsiso: I did. Actually, when I had my degree I was like, “OK, I’m done. I can die now!” And it was such a good feeling. I didn’t participate in the graduation ceremony when I finished my undergraduate because I thought it was all about the institution making money. But when I graduated with an MFA, I actually thought of people who I was looking after and why it was that I was able to finish this school. Because I looked at somebody, because somebody told me I could do this. And when I thought about my nieces and nephews and people from my community and other people — just people in general who think that they can’t do this because of whatever reason — I thought, “I should walk. And I should wear my attire, just to say, ‘If I can, you also can.’” So I did walk on the stage when I graduated with my MFA.

I also learned that the next stage after you’re done with your personal goals is to give back to the community, you know? I feel like I’m in the second stage now.

I also learned that the next stage after you’re done with your personal goals is to give back to the community, you know? I feel like I’m in the second stage now.

Pier Carlo: You’ve talked about your goal now being giving back to the community. Do you have an artistic goal that you think you’re trying to reach, whether in terms of the reach of your work or an aesthetic goal you’re trying to reach? Do you have a dream in that way?

Narsiso: Yeah, I do. I have dreams about my own practice, not necessarily change in what I’m doing or what I’m focusing on but in reaching out to other communities. I feel like soon hopefully I want to meet other workers within the agricultural industry, maybe travel to different places and experience and hear the stories of people who work in, let’s say, the banana plantations or the cocoa bean plantations, the coffee plantations in South America. And what is the lifestyle like? Is it fair? What kind of people work in the fields over there?

Yeah, I’d like for them to be also represented in art. I like those challenges, and hopefully one day it’ll happen, you know?

June 14, 2021