Tariq Tarey

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

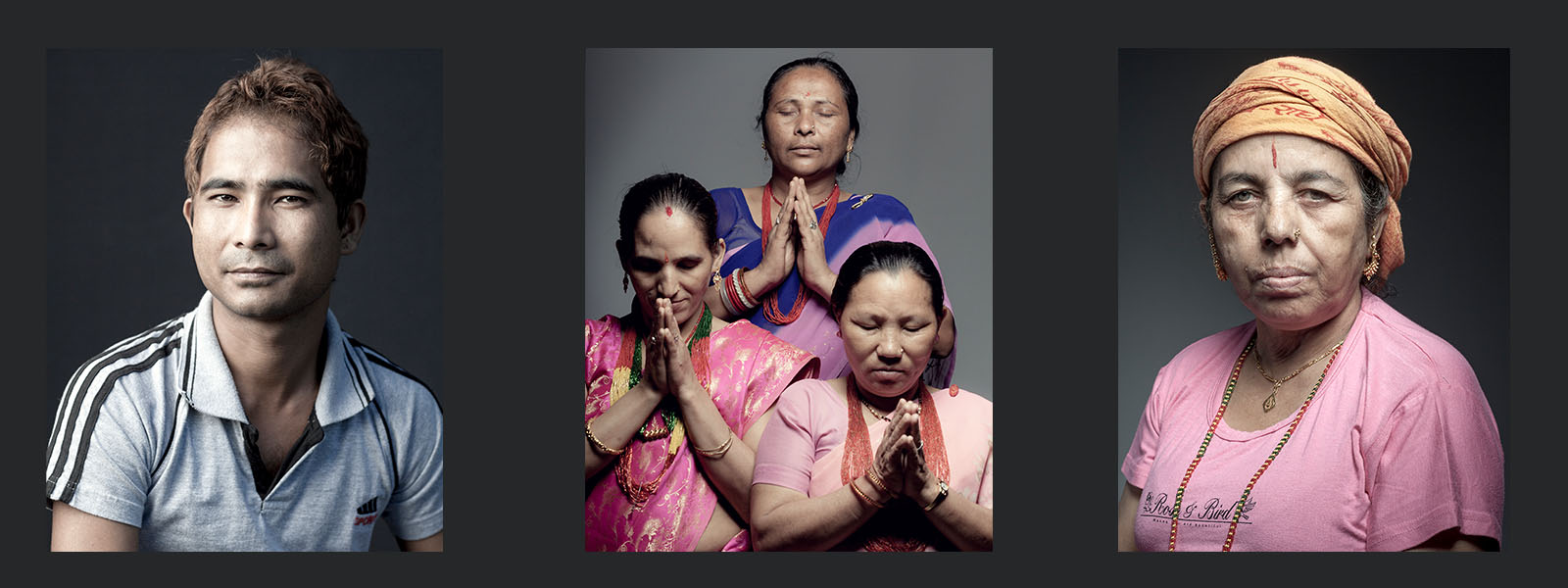

Tariq Tarey is a documentary photographer and filmmaker based in Columbus, OH. Over the years, he has captured thousands of portraits of refugees from around the world whom the U.S. government has resettled in Central Ohio.

Tariq himself arrived in the States in the mid ’90s as a refugee from his native Somalia. He therefore has a particular empathy for his subjects, many of whom like him hail from Somalia but also from a myriad global locations, from Nepal and Iraq to the Democratic Republic of Congo and more recently Ukraine. His photos evince a keen artistic eye that captures each subject’s inherent dignity as well as the countless stories of home, upheaval and loss suggested in their eyes and the way light and shadows contour their features.

His passion is not only for his work’s artistic expression, though, but also for its documentary value. Tariq wants to ensure that the refugees’ faces and the histories they contain are photographed and then archived with the same care shown to their antecedents who in centuries past arrived largely from Europe through Ellis Island.

Tariq has also conducted photographic projects in refugee camps around the world and has directed documentary films, including "Women, War and Resettlement: Nasro’s Journey" and "Silsilad," which have been featured on PBS, and most recently "The Darien Gap," which was showcased at the second United States Conference on African Immigrant and Refugee Health. His photos have been exhibited in several institutions, including the Ross Museum and Wright State University, and several are now part of the permanent collections at the Columbus Museum of Art and the Ross Museum.

His deep knowledge of the refugee experience stems not only from his own personal experience. For years now he has worked as the Director of Refugee Social Services at Jewish Family Services in Columbus, Ohio. He also serves on Ohio’s New African Immigrants Commission and the Franklin County Board of Commissioners' New American Advisory Council.

In this interview, Tariq describes how he launched his photographic career soon after arriving in Ohio and explains why his work remains crucial as history keeps repeating itself.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- What made you want to buy your first camera?

- How did you develop your practice of approaching your subjects? It is so easy to exploit people who are in a very vulnerable position to tell a story … how did you develop your code of conduct?

- How do you prepare yourself for each shoot?

- When you look back at your earliest photos and compare them to the art you’re making today, what do you think was the biggest artistic lesson you had to teach yourself?

- How do your subjects react to seeing themselves in an exhibition of yours?

- What do you think you’ve learned about refugees that you wouldn’t have learned had you not started taking photos?

- We see a lot of photos of refugees or immigrants who are trying to come to the country… but they’re selected by editors. When you look at what’s being shown to us, what do you think we’re not seeing?

- If you were granted two minutes in front of Congress, what’s one step they could take to make the whole situation on the southern border easier? What would you tell them in those two minutes?

- Do you have an artistic practice that’s completely unrelated to refugees? Do you have a way you recharge artistically that’s not connected to those stories?

Pier Carlo Talenti: What made you want to buy your first camera, that Canon AE-1?

Tariq Tarey: Honestly, you know, my father was not a photographer, my grandfather was not an artist, none of my lineage has any art base, but I just had this feeling. I was like, “You know what? I just love seeing beautiful photographs.” And I didn’t know what a beautiful photograph even was. I just loved the idea of capturing something.

Fast-forward a few months after I spent many, many, many dollars on underexposed film at Walgreens. There’s a street in Columbus called High Street, and within that there was a camera store called Midwest Photo Exchange. The young man who was working there was Somali, and his name is Abdi Roble. That name and that person changed the way in which I view photography. Because of him, I realized the power of photography.

He is a self-taught photographer from Somalia, same history as me. Left Somalia when he was a kid, came to the U.S. as either student or something like that. Things didn’t work out, the civil war breaks out, he ends up in the United States, and all of a sudden, he’s working at a camera store. And to me, when I look at a photographer, I’m thinking about somebody who is … National Geographic, a white guy, you know what I mean? That’s the sort of the idol that you are looking at. But to see a young Somali man working at a camera store sponsored by Leica. If you don’t know what Leica is, Leica is the German camera manufacturer that is sought out around the world. Leica sponsors him, and he travels to Cuba in the early 2000s, and he’s got this exhibit. And I’m thinking, “You’re Somali. You’re not supposed to have all of this. This is a white-guy territory.” He took me under his wing and learned the craft from a wide variety of other photographers.

I feel like the other thing that made me realize the power of photography is also where I worked as a professional. I’m a director of a large refugee program at an agency called Jewish Family Services. That itself, seeing the history of the Holocaust through the eyes of the Jewish people, the importance of capturing photos, the history of people arriving in the United States from Europe to Ellis Island, that is where the dots are being connected for me. I thought, “OK, I need to do something with my thing that I’ve learned and the skill that I’ve gained.”

It is about making sure that the people who are arriving today who look like me are archived and making sure that their history is also preserved. And not through Snapchat and Facebook and all these phone photos but a respected Gordon Parks style of photography, black and white. I want to do the same thing that the Europeans got. I want to make sure that the African refugees and the Middle Easterners or what have you who are coming to the United States today are also being captured professionally and with an archive mindset.

Pier Carlo: How did you develop your practice of approaching your subjects to start with? So many of your subjects, I imagine, are very vulnerable. I’m guessing they’re fairly new arrivals to the country. And you mentioned National Geographic. It is so easy to exploit people who are in a very vulnerable position to tell a story that’s foreign to Americans. You don’t do that, but I guess I’m asking how did you develop your code of conduct?

Tariq: It really is a common-sense code of conduct because I am telling my story in some sense. Leaving my country not because of my choice, we have in common; learning a new language, we have that in common; being confused all the time, we have that in common; finding Americans as fast-walking, fast-talking people, we have that in common. So I have a lot of common, no matter if they’re from Afghanistan, if they’re from Sierra Leone, if they’re from Somalia. At least they know I come in peace.

My code of conduct is not to pressure anyone to sit in front of my camera. My code of conduct is to respect the person. If any time they decided not to be part of my work, I’m good, absolutely. No money exchange between us, so I’m not going to pay you because then it dilutes the whole system. So there’s a lot of journalistic ethics with the code of conduct. It’s sort of morphed into that, but it’s also common sense.

There are studio photos, but there are also outdoor photos. Outdoor photos is when I am in the neighborhood — I’ve been invited to an event or party — so I set up my backdrop and people come by.

Pier Carlo: You’ve also traveled abroad for your photography, is that right?

Tariq: Yes, many refugee camps from Africa to Europe. To Panama as well. Yeah, absolutely.

Pier Carlo: How do you prepare yourself for each shoot? At this point in your work with Jewish Family Services, you’ve worked with so many different populations, so you’ve become an expert in the challenges that refugees face coming all over the globe. But do you have to prepare yourself for each shoot, particularly if you’re going to photograph someone from a culture that you’re less familiar with?

Tariq: Remember at the beginning of our conversation I told you the many places I lived in, including India? A lot of that that comes into play. So when do you make an eye contact? When do you shake hands? When don’t you shake hands? How do you convince somebody to sit for you? All these things are ingrained in me without me pretending to learn or to do that. Iraqis and Syrians have a similar culture. We Somalis have a similar culture, so I know when to use that. I lived as a child in India, so if I’m photographing Bhutanese-Nepali or Nepali refugees here in Columbus, I do know a few words in Hindi, I do know the Hindi customs. There’s a lot of that, not only from a technical point of view but on a human level. I do know when not to step on a bad situation or not to set somebody off by saying the wrong thing or doing the wrong thing.

From a technical point, how do I prepare myself? It really depends on the project itself. Sometimes I would photograph on a large format, like a 4-by-5 film camera. Sometimes I want to be nimble and quick, so I would have a medium format, like a Mamiya 67. It depends on where I’m at. For the larger projects, for the long-term project, it is 99% on a large format 4-by-5 field camera. I also extensively use Mamiya 67 or Pentax 67. So those are for the sort of quicker “I’m in refugee camp; I can’t set up for a long time; I’m going to be quick.” But also it’s a large-enough negative that I could print larger work.

Pier Carlo: I heard you saying, I think, in an interview that the reason you prefer film is that, in terms of archiving purposes, you have more faith in a negative than you do digital information. Or am I making that up?

Tariq: No, you’re not making that up. Yes, I’ve said it, and most people are sick of me saying it all the time. But listen to this. Do you remember the floppy disc?

Pier Carlo: Yeah, sure.

Tariq: What happened to it?

Pier Carlo: Yeah.

Tariq: Exactly my point. Yes, we can always copy things to a newer medium and newer things, but even the Firewire on your Mac just 10, 15 years ago, what happened to it? Technology is changing so fast that we cannot keep up with it. I have mini DVDs. Remember those mini DVDs that we used to film our family? I have a bunch of that on my kid’s birth. And now the other day I wanted to convert it to put it in my hard drive or my server. I’m telling you, I was having a tough time. I had to connect a cable to another cable to another cable. I had to connect the camera —

Pier Carlo: And they’re not that old.

Tariq: And they’re not even that old. My kid is like 17 years old. So forget it. But American Civil War, 1865, you can still print those. Right now, today. All you need is a chemical, all you need is one light bulb, and you’re good to go.

The point I’m making is, yeah, you can shoot the fanciest digital and good for you, I support you, but let me be happy with what I have. [He laughs.] I know. My wife says I’m very grumpy all the time, but you know what I mean? Just … life is good.

Father and Son, 2016, Petra Refugee Camp, Greece; Photo: Tariq Tarey

Pier Carlo: When you look back at your earliest photos and compare them to the art you’re making today, what do you think was the biggest artistic lesson you had to teach yourself?

Tariq: There are so many. I feel like it’s really to talk the art language. Filmmakers, photographers, artists, especially if you grew up in ... . If you’re not trained as an artist or you didn’t go to school for art, explaining your way about your work is very difficult because you don’t know the language of what collectors want, what museums want to hear. All those things are very difficult. For me, I think, I had to learn the language of, “How can I make you care about my work? How do I make you pay attention?” And “Is my work only for the sake of art, or is it art that I want to be teaching you something about forced migration and human-rights violations and immigration and integration?” It’s very complicated.

Pier Carlo: Did you answer that question for yourself? The distinction between “Is it art or documentary? Or a mix of both?” Is that distinction at all useful to you?

Tariq: It depends on where I am. If I am talking to someone who’s an art collector, the language is, yes, it’s advocacy, but that’s not the heavy work. The heavy conversation is archivability. Is it one of a kind? Does it have value? Is the human expression there? Does it make you look at it and feel an emotion a certain way? For the art world. But if I’m talking to someone like you who cares about human rights and cares about the conversation about not only the human rights but art as well, then our conversation is focused on, how do people get to United States? How do people apply for refugee status? What is the Charter of the United Nations and the Geneva Convention for Human Rights? Those are different conversations than art. And my work also talks about those things.

Pier Carlo: You talked about wanting your images to be accessible to a broad range of people. I wonder if you could talk about how your subjects react to seeing themselves in an exhibition of yours.

Tariq: That’s a good question. When I’m photographing them at first, they’re like, “Tariq, why do you find me interesting? What’s so interesting about me? You have 500 refugees that you could photograph. What is it about me?” To answer that question, I’m like, “Because you’re unique and you’re different. We’re all different. Yes, we may have the shared experience, but not all of us went through the same process. I want to learn more about you.”

Pier Carlo: You’ve learned so much about refugees through your work and through your experience. What do you think you’ve learned about refugees that you wouldn’t have learned had you not started taking photos?

Tariq: After World War II, we said never again. And Cambodia happened in the '70s, and then Bosnia happened after that and then Rwanda. And then the one that surprised me the most, once the world learned everything about genocide and how bad it is, you have the Yazidis, through ISIS. That’s the 21st century genocide.

If I wasn’t involved in refugee resettlement and welcoming refugees and refugee policies and if I was not a photographer, I don’t think I would’ve paid as much attention as to what’s happening in the world. It’s sort of an obsession. It’s a healing for me through my past, what I’ve gone through and what most refugees have gone through. To me, I feel like this is therapy, to make sure I help refugees as much as I can because it’s my story, it is who I am. It is what identifies me as a person who lost his country, who came to the West, who is using the tools of the West to help whoever I can who’s gone through the same historical situations.

I want to be the bridge; I want to be the conduit. I want to be the person that brings that dialogue and discussion through art because everybody likes to go to an art exhibit or photo exhibit. If the dialogue is about learning from one another, I’m doing my job and I’m doing what I’m supposed to be doing

Pier Carlo: On our front pages, we’re seeing a lot of photos of refugees or immigrants who are trying to come to the country. They’re taken by very good photographers, but they’re selected by editors. When you look at what’s being shown to us, what do you think we’re not seeing?

Tariq: Yeah, we’re not seeing many things. But let me go back, if I can help the listeners first. The idea is historically the difference between a refugee and an immigrant, it’s a defined law, an international law that was set in 1951 called the Geneva Convention. The idea was any person who’s being persecuted based on their religion, based on the ethnicity, based on the political affiliation, based on their even sexuality, if persons are being persecuted or harmed, they are allowed to leave that country, their birth country or the country that’s doing that to them, and apply for a refugee asylum to say, “Hey, if I go back, I’ll be killed. Please help me.” We as Americans signed onto that law, signed onto that agreement. So if somebody comes to the border legally and says, “Hey, I’m a refugee. I need your help,” we have to listen to them.

Closing the border itself based on wanting to score political points, that is beside the point. We as Americans have signed onto that. Whether you are Democrat or Republican, whether you are liberal or conservative, we signed on to that in the 1950s, helping the European refugees who were coming to the United States at the time. Now that that’s not happening, we also need to open our hearts and really figure that out. I just want to clearly say that before I answer your question.

Pier Carlo: Yeah, thank you.

Tariq: So what are we not seeing is the human story to it. What drove that Honduran woman, that Venezuelan young mother with her two children, what drove her from this entire continent all the way to Texas? She was photographed, and all you see is a name maybe and the location where that photo was taken and the writer talks about the general story, but what’s missing is she’s a daughter of somebody. She’s a person that walked for thousands of miles, probably most likely sexually violated. What’s her case? Why did she leave the place? That’s really what’s missing from the context of it.

As an American — and all of us as Americans — what’s happening in their country that they find it so hell that they’re leaving? And what could our country do to help them stay in their country, build it, support it? Because you’ve heard of the Marshall Plan after World War II. What did we do with Germany right after World War II? We put every single resource we could to give support to that country. And are you saying that Honduras cannot be Germany? What’s the difference?

Pier Carlo: I am going to ask you an unfair question because it’s impossible to answer. If you were granted two minutes in front of Congress, what's one step they could take to make the whole situation on the southern border easier? What are they ignoring? What would you tell them in those two minutes?

Tariq: It’s very difficult to give you only two minutes, right?

Pier Carlo: Yeah, I know.

Tariq: I would separate facts from fiction. The fact is, we as Americans, what makes this country what it is — and I’m saying this truthfully — is because of the diversity and the respect for the Constitution and the laws that we have on our books. We said we will protect human beings who are suffering from tyranny and oppression and persecution. We said that, and we signed onto it.

Second is we also need to look at what is fueling people to come to the United States and why those countries are broken down. And could we look into it? And obviously you are only giving me two minutes, but I would definitely focus on not politicizing this situation. It doesn’t have to be.

Pier Carlo: Your job as a refugee-resettlement expert or counselor is so closely related to your artistic practice. It must be incredibly stressful. You hear a lot of trauma in your daily life. Do you have an artistic practice that’s completely unrelated to refugees? Do you have a way you recharge artistically that’s not connected to those stories?

Tariq: Yes. It is still photography, but it’s not focused on refugees. I’m working on a project about Cuba. I find Cuba fascinating, and it reminds me of my childhood quite a bit actually every time that I visit. I’ve been there many times now. I’m working on a project about how ... . So race and ethnicity from a capitalist society like the United States I do understand it because I’ve lived here most of my life. I do understand race relations in the capitalist society, but I don’t understand race relations in the Communist sense. I’m exploring what that looks like.

Like I said, I’ve been there many, many times and I’ve been doing portraiture about people’s different looks. Spaniards, "mulattos," and "negros." They wouldn’t even call me Black. They would say I’m somewhat mixed, which I’m thinking to myself, “Dude, I’m African. I have no white in me, period.” You and I know slavery, Civil War, Jim Crow, civil rights and so forth and so on. Redlining. There’s many things that you and I know about the United States race relations, but what do race relations look like in the Communist society? Are they all equal the way they say it, or are they not?

So if you ask me what other art, it’s still photography, but it’s not related to the documentary stuff that I do with my refugee work. It’s about learning. And also it gives me a chance to take my camera and travel to another country and just learn about the culture. It really is fascinating, by the way. Have you been to Cuba?

Pier Carlo: I have not. After the previous administration, it got more difficult to go. How have you been able to go so often?

Tariq: Yeah, it’s very tricky. But when I go in, and genuinely I mean it, I am going to support the Cuban people. So you could go and support the Cuban people. You’re not economically influencing, you’re not buying anything from there. You’re just supporting the Cuban people by either renting a place, supporting them, buying things, supporting them in any way possible. So you’re able to do that. But it could be closed tomorrow. By the time this podcast gets released, who knows what could happen?

June 25, 2024