Valencia James

The views and opinions expressed by speakers and presenters in connection with Art Restart are their own, and not an endorsement by the Thomas S. Kenan Institute for the Arts and the UNC School of the Arts. This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Born and raised in Barbados, Valencia James studied modern dance in Budapest, Hungary and had the opportunity to perform work by some of the world’s most adventurous choreographers in international venues. However, it wasn’t until she started asking questions about what role artificial intelligence might play in shaping the future of the performing arts that she truly found her passion.

Today Valencia works with innovative technologists and scientists to create collaborative performance pieces that blur the boundary between artificial intelligence and the human performer and that hint at how different the experience of performance may be for future artists and audiences alike. She and her collaborators have presented their research and AI-infused work at conferences all over the world. Two days after this interview, dancing in front of a camera in her home in Redwood City, CA, she premiered a brand-new live immersive piece titled “Suga’: A Live Virtual Dance Performance” in the New Frontier exhibition of the 2022 Sundance Film Festival, proving that the worlds of film and live performance are very much already blending.

In this interview with Pier Carlo Talenti, Valencia explains how her work with technology has influenced her creativity and how an ethos of accessibility is proving useful in guiding her and her collaborators on their exploratory forays.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- How did your interest in marrying your art to technology come about? At what point in your artistic development did that idea arise?

- How has your understanding of dance evolved as a result?

- So what can you learn from an avatar that is not inhabiting a human body?

- Can you give a specific example of a movement or a particular instance in “Between the World and Me” where you felt you developed something that you couldn’t have without your AI experience?

- You talked about wanting to think about disrupting the world of dance through technology. In what other ways do you think the world of dance can and should be disrupted these days?

- When everything was shutting down, you came up with a new program [the Volumetric Performance Toolbox]. Can you describe it and talk about how it emerged?

- So you just presented something at the Sundance Film Festival this year. … Can you talk about what people will see?

- I imagine that a lot of artists who might be listening to this might be intimidated about approaching scientists to work with them, to collaborate with them. What would you tell them?

- You described how your work with AI has affected your own artistry. What are you hearing from the scientists and the technologists you’re working with about how your art is affecting their work and their outlook?

- How do you describe yourself when somebody asks you what do you do? Do you say dancer/choreographer?

- Can you talk about a pie-in-the-sky dream project that you are dreaming of?

- What are you hoping that this work of yours that you’re doing will contribute to the field of dance?

Pier Carlo Talenti: How did your interest in marrying your art to technology come about? At what point in your artistic development did that idea arise?

Valencia James: I think it was around 2013. I was still working in Hungary, and there are amazing opportunities to create because studio space is very affordable. I had the opportunity to do a research residency with my partner, Botond Bognar, and he was just starting to visit Silicon Valley. He would come back and talk about things like disruptive technologies, and we would watch presentations around how technology is changing our lives so much, especially machine learning and artificial intelligence.

I started to wonder about, “Well, I see how the taxi and the hotel industries are disrupted, so I wonder what will happen in the performing arts, where the human body is so important?” We took the opportunity to ask some questions. If I could somehow teach a computer to dance and through that have a duet with an avatar that would be able to learn my movements and then extend them and show me new ones, what would that mean for live performance? How would it affect its future? But then I found the most important question was, how is my understanding of dance evolving because of this interaction?

Pier Carlo: And could you answer that question of yours? How has your understanding of dance evolved as a result?

Valencia: It became this multi-year project entitled "AI_am." I collaborated with three technologists: Alex Berman, Gábor Papp and Gáspár Hajdu. We didn’t have much money, but because of that, we created a system, a tool that caused the dancing avatar to improvise. And so it became this creative partner. We didn’t give it any limitations so it could do very strange movements, and so I found that extended my idea of what dance could be and what a so-called movement could be. I could break out of certain movement habits.

Pier Carlo: I’ve had the opportunity to watch some video of you dancing with the avatar. The avatar can do movements that are literally impossible for the human body.

Valencia: Yeah.

Pier Carlo: So what can you learn from an avatar that is not inhabiting a human body?

Valencia: Because it just dances and dances and never gets tired and doesn’t stop, I found that it was just mesmerizing to watch the movements. It elicited this urge to join in the dance, to imitate, to riff off of the movements of that visual stimulus that I was seeing.

I felt compelled to just keep moving and moving until I couldn’t move anymore, or I was very intrigued to try to imitate those humanly impossible poses and see where pushing those limits of my body can take me.

I found that it started to push me beyond my limits. I felt compelled to just keep moving and moving until I couldn’t move anymore, or I was very intrigued to try to imitate those humanly impossible poses and see where pushing those limits of my body can take me.

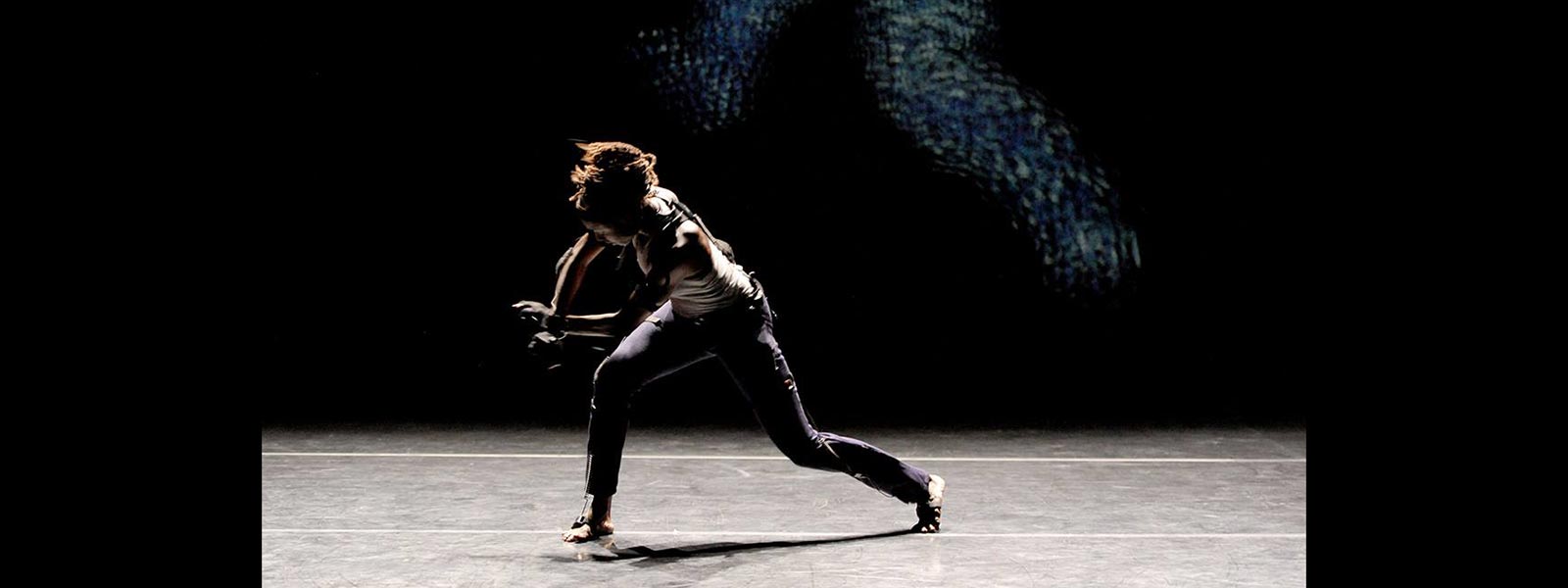

It brought a new type of movement quality that then I was able to use in another piece called “Between the World and Me.” I found trying to do these contortions, it gave this poetic voice or this poetic language to talk about how I felt in the Hungarian society at that time.

Pier Carlo: So “Between the World and Me” was not a dance with the avatar, but you’re saying the movement vocabulary was influenced by your experience with the computer. Is that right?

Valencia: Yes. This research with my project “AI_am” brought about a way of finding this movement language that I found was a great metaphor for what it’s like to be a Black woman in a primarily white society. It gave voice to what it’s like to have these microaggressions or awkward situations that were happening daily on the street. So that was something unexpected.

Pier Carlo: Can you give a specific example of a movement or a particular instance in “Between the World and Me” where you felt you developed something that you couldn’t have without your AI experience?

Valencia: I chose to use primarily quite disjointed movements. There are points in the piece — the connecting thread between the different scenes that I developed — where I move from one part of the stage to the other, and I would go from a very extreme pose to another extreme pose. I guess the closest movement form to that might be flexing, like how far can my shoulder joints wrap around the back of my body? Or some kinds of inversions that may have my legs kind of wrapping around in a new way.

It was just figuring out what’s that sensation and seeing what kind of movement is coming from that.

Pier Carlo: You talked about wanting to think about disrupting the world of dance through technology. In what other ways do you think the world of dance can and should be disrupted these days?

My motivation is not to disrupt, but just thinking around that: What does disruption mean? Because the world is changing so much at a pace that it’s not, 'Will it happen or not?' It is happening, so what are we doing with it?

Valencia: My motivation is not to disrupt, but just thinking around that: What does disruption mean? Because the world is changing so much at a pace that it’s not, “Will it happen or not?” It is happening, so what are we doing with it? I’m curious about how it could extend our creativity. How can we create new opportunities from this rather than feel like we are victims? How can we be more agents in it?

Something that I have noticed is the access to actually engaging with these new technologies for artists, that’s one thing. Because this type of research requires not only a lot of funding but also knowing technologists who are open to collaboration. One thing that I’ve been quite fortunate with is finding technologists to work with who are receptive to new ideas outside of their domain. The other is audience access, so thinking about how contemporary arts and contemporary dance and theater can reach new audiences, audiences who would not necessarily pay for a theater ticket.

Pier Carlo: Since you’ve brought up how technology can provide new opportunities, now’s a good time to talk about the Volumetric Performance Toolbox, which you developed during the pandemic. When everything was shutting down, you came up with a new program. Can you describe it and talk about how it emerged?

Valencia: Yes. Just around the time of the lockdown, I had been contacted about restaging a piece from “AI_am.” We had just created an evening-length show called “AI am here,” and then that got canceled. But because I was thinking about restaging it and I always wanted to figure out how to get the dancing avatar into the theater space — like maybe using augmented-reality technology — when that got canceled, it dawned on me: Theaters are closed, but what if I as the performer can perform in the computer? How can I get into the computer and dance there?

I had contacted a friend. He is a creative technologist called Sorob Louie, and he thought the idea was really great and connected me with his mentor, Thomas Wester, another amazing creative technologist. At that time, Thomas had been looking at volumetric recordings, volumetric video. That means basically using a special camera that can understand how far you are from it — it’s a depth-sensing camera — to recreate a 3D video rather than a flat 2D video like we’re used to on Zoom, creating a way to have the performer in virtual space and not need an avatar so you can see them in real time from wherever they’re performing. It’s all using depth-sensing cameras.

That’s how this project was born. We were able to apply for a residency from Eyebeam. It was a remote residency called Rapid Response. Through that support, we did a lot of research and development and came up with this toolkit that involves open-source software. We used Mozilla Hubs social virtuality platform, which is a free platform by Mozilla where audiences can go into a virtual performance space using only their computers and web browsers. We also developed open hardware, a low-cost kit that any artist can use and have this video broadcasted from their living rooms.

This is what we’ve been working with.

Pier Carlo: Did you all decide as a team early on that it would be open-source or that it wouldn’t cost very much to get that package?

Valencia: Yes, that was one of the first goals, the first question: "OK, how can we create something that an artist can afford?" Because at the time we saw that a lot of the technology requires a very expensive computer and a very expensive camera, so one of the things that Sorob suggested was, how can we do this using a very small computer called Raspberry Pi. It’s a very tiny computer box you can program. So we ended up having a kit that is just about $350.

During the project, we were able to develop an educational program. We had invited seven artists and we shipped each artist a kit, and we did this communal co-learning and co-creation with that.

Pier Carlo: What was the feedback you got back from the seven artists?

It was amazing just to learn about this technology together. I found that they were super-open. They came up with amazing solutions to performances. The kit has its limitations, so they embraced the limitations and made some beautiful performances from that.

Valencia: It was amazing just to learn about this technology together. I found that they were super-open. They came up with amazing solutions to performances. The kit has its limitations, so they embraced the limitations and made some beautiful performances from that.

We did this live event on Mozilla Hubs. Also we were able to do a launch with Eyebeam and also make an installation where we projected the performance that was happening online onto the public-facing doors of Abrons Arts Center in New York. It was very successful.

Pier Carlo: Were these all dancers or different kinds of performance artists?

Valencia: There were some dancers but also 3D artists. There’s a sound artist. They’re all quite interdisciplinary, because one of the challenges that we were facing was about how to make this technology actually accessible. I found for me as a dance artist, it’s very hard to make that step, but if I have a colleague who knows a bit more about building 3D worlds, then we can collaborate. It’s much easier to approach new technology in that way. So that was our strategy for this residency.

Pier Carlo: So you just presented something at the Sundance Film Festival this year. Is that correct?

Valencia: Well, it’s about to happen.

Pier Carlo: Oh!

Valencia: Yes, on Friday.

Pier Carlo: Can you talk about what people will see on Friday?

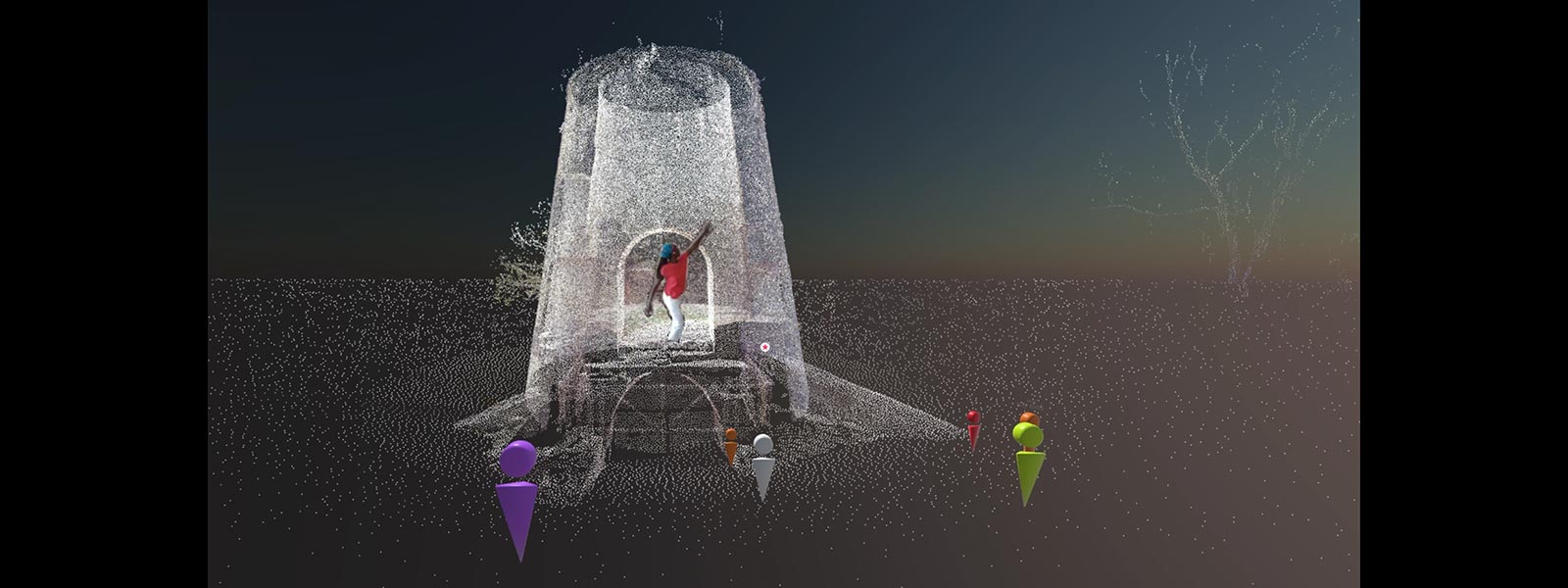

Valencia: Through this project, Volumetric Performance Toolbox, I developed a virtual performance called “Suga’: A Live Virtual Dance Performance.” It’s a collective immersive experience where the audience meets in and navigates around this virtual world. As the performer, I perform from my living room into this virtual space. The story is about the transatlantic slave trade and the establishment of the sugar industry in the Caribbean.

I use this virtual performance as a way to honor my ancestors and think of virtual environments as a place where you can reclaim spaces that are historically filled with pain and injustice with virtual acts of healing.

I use this virtual performance as a way to honor my ancestors and think of virtual environments as a place where you can reclaim spaces that are historically filled with pain and injustice with virtual acts of healing. So my dance performance is like a healing ritual and commemorating the resilience and beauty of our people.

This work has been selected for this year’s New Frontier Exhibition at Sundance Film Festival. The New Frontier and the festival actually open tomorrow, January 20th, and we will do a run of six performances throughout this Friday the 21st, Saturday the 22nd, and next Thursday the 27th. And there’ll be two performances daily.

Pier Carlo: So at a set time you will be in your living room.

Valencia: Yes.

Pier Carlo: And you will perform live for a virtual audience. And the audience will see you performing in a virtual environment. Is that correct?

Valencia: Yes. For this, we found the spatial data of the Annenberg Sugar Mill. This is a sugar mill site in St. John, the U.S. Virgin Islands. It was open data scanned by a company called CyArk. They go around the world scanning many World Heritage sites, and they make it available for free online. We were able to download this data and reproduce it in Mozilla Hubs, and so I was able to place my 3D video in there so that it looks like I’m actually dancing on or within the sugar mill.

Pier Carlo: I see. And the sugar mill is, of course, in terms of the history of slavery and sugar, a crucial site.

Valencia: Yes, yes. The sugar mill was where many, many people of African descent lost their lives. It was forced labor, and of course there’s a lot of pain still there.

The thing is with this piece what I want to highlight is that yes, slavery was abolished in the latter part in the 19th century but the legacy of it still lives on. The laws that were established 400 years ago in the islands, especially in Barbados where I’m from, were the blueprint for the laws and the systems of control that still oppress Black people today in the U.S. and around the world.

So I think for this, I believe that it’s really important to understand the origins of these injustices and understand it’s not something that “it’s just history; it’s gone.” These are real laws and economic systems that still exist today. It’s my aim to highlight that in this work as well.

Pier Carlo: For the audience to see a Barbadian woman dancing and reclaiming this historically loaded space without actually having to be in St. John, right?

Valencia: Yes, or even be in the same physical space. We can do this virtually.

I also have to acknowledge and thank my collaborators Thomas Wester, Simon Boas, Holly Newlands, Marin Vesely, Sandrine Malary, Terri Ayanna Wright and Carlos Johns-Davila, who generously gave of all their skills and energy to make this work what it is. And yes, we’ll be very happy to have participants join us live in Mozilla Hubs for this performance.

Pier Carlo: I imagine that a lot of artists who might be listening to this might be intimidated about approaching scientists to work with them, to collaborate with them. What would you tell them?

Valencia: Well, I do understand the hesitancy and even fear. I personally find it really exciting to think about, how can, say, your artistic practice or your choreographic approach, how might it be applied in another medium, like in computer science? Or how might computer approaches or scientific approaches influence or inspire your work or your choreography or your painting?

I would say you start small. Just start speaking to someone whose work you find interesting. I think just a conversation is already a wonderful step in the direction if you want to explore interdisciplinary collaboration.

Pier Carlo: You described how your work with AI has affected your own artistry. What are you hearing from the scientists and the technologists you’re working with about how your art is affecting their work and their outlook?

Valencia: Well, I don’t know. The technologists I work with are already themselves artists. [She laughs.]

Pier Carlo: Oh, OK.

Valencia: One thing that’s been really important with my projects is that it’s been the needs of the artist, in terms of free expression and accessibility, that’s always been the first question, the first framing question. So that’s always been the drive towards what technology we use and how it is developed. I think that’s very important in any art-and-technology project because I find that if you lead with the technology, there are a lot of assumptions. You know, when you’re dealing with a certain technology, it’s built with certain assumptions of the people who’ve designed it.

A lot of times, we find ourselves having to kind of change the way we do things because the way that the technology has been designed, it shows us how to use it. And so that becomes a big challenge for making art, because you have your way of how you want to express yourself. So if you can find a collaborator who would be open to picking apart the system and building it from the ground up again with the artist’s needs in mind, I think it’s a more beneficial kind of path.

I feel like when it comes to designing human-centered technologies that really work for us rather than against us or disrupt how we do things, it might be a good way of thinking of moving forward in the future. What if we can build things that are really made by and for the people that will use them?

Pier Carlo: It sounds like how you found the perfect collaborators is that there was an ethos to start with in the projects, namely that they would be accessible. It feels like there was an act of generosity at the heart of it.

Valencia: Yes, everyone is super-generous. The thing is with any artwork, it’s very expensive, and then working with technology makes it even more expensive to develop. My collaborators are very generous in the giving of their time and their expertise. But we have this common goal and common ethos that unites us, so definitely I’m forever grateful for them.

Pier Carlo: I’m sitting here thinking that describing you as a dancer/choreographer doesn’t even begin to capture a tenth of what you do. How do you describe yourself when somebody asks you what do you do? Do you say dancer/choreographer?

Valencia: I don’t use the word choreographer because I feel like I’m still learning the craft, you know? I usually say I’m a performer and researcher, and maybe I will add maker if the word count allows. [She laughs.] I guess I’m still discovering that, but I definitely like to say I work through interdisciplinary collaborations. It’s evolving.

What’s most important, I think, has been that in the past couple months my mind has literally been expanded into pushing through those limits of what I thought I could do. I was really very much still thinking in the frame of dance, and then in the past couple months, I’ve been thinking about, “Well, my work can also live in visual arts or even gaming." These are ideas that literally came up in the past couple weeks of meeting people in gaming and understanding, “Well, yeah, gaming is an extension of theater!” This is something I’m now realizing, and I want to learn more about that.

Pier Carlo: It’s interesting. It also makes me think that we think of gaming as being in a way so unembodied, that somebody’s just in their chair with a joystick, but there’s something so interesting about having a movement artist actually changing the experience of how a game is experienced.

Valencia: Yes. I mean, it depends on how it’s designed. I still have yet to really understand, but I’m thinking there is a certain amount of performance. That’s something I would like to research more, about how does it feel for the actual person in experiencing themselves in the game? The way the technology is designed right now, it does necessitate you having a joystick or you’re using four keys on the computer, but then what is happening in that person’s body? What kind of mirror neurons are firing?

Pier Carlo: And it sounds like you’ll be at the forefront of AR and VR research going forward.

I feel that because of our work, which is very much embodied, we understand a lot of the needs and a lot of pitfalls to avoid when looking at how we are engaging people in spatial design and spatial computing. There is a lot that we can offer to this realm.

Valencia: Yes. And I want to maybe make this a call to action for any choreographer and dancers, performers, theater artists out there who might be listening to this, that there is a very big need for our expertise in these technologies and the development and design of them going forward. I feel that because of our work, which is very much embodied, we understand a lot of the needs and a lot of pitfalls to avoid when looking at how we are engaging people in spatial design and spatial computing. There is a lot that we can offer to this realm.

I think that’s where that interdisciplinary, cross-disciplinary research and collaboration with technologists becomes very important.

Pier Carlo: Can you talk about a pie-in-the-sky dream project that you are dreaming of?

Valencia: I’m applying to go back to school to do an MFA, and so my dream right now is to acquire those critical and technical skills and learn those tools, like programming and so on, in a more hands-on way. I guess it’s not pie-in-the-sky, but I want to really delve into the study and creation in interactive immersive technologies and I’m looking at how I can use those tools to continue telling my stories of marginalized communities.

Pier Carlo: And I think it’s early in your career to be asking this question but, what the heck, I’ll ask it. What are you hoping that this work of yours that you’re doing will contribute to the field of dance?

Valencia: When I approach emerging technologies, I’m always asking, “How can this enhance my creativity? How can it push me into discoveries that I wouldn’t otherwise have been able to find?” I hope that the work that I do and the tools that I’ve created in the process can be used by many. This is also the next step for me, looking and finding out the ways of making the tools that I've been very fortunate to make collaboratively with the people I've worked with something that's accessible.

January 24, 2022