Artist As Leader: Jonah Bokaer

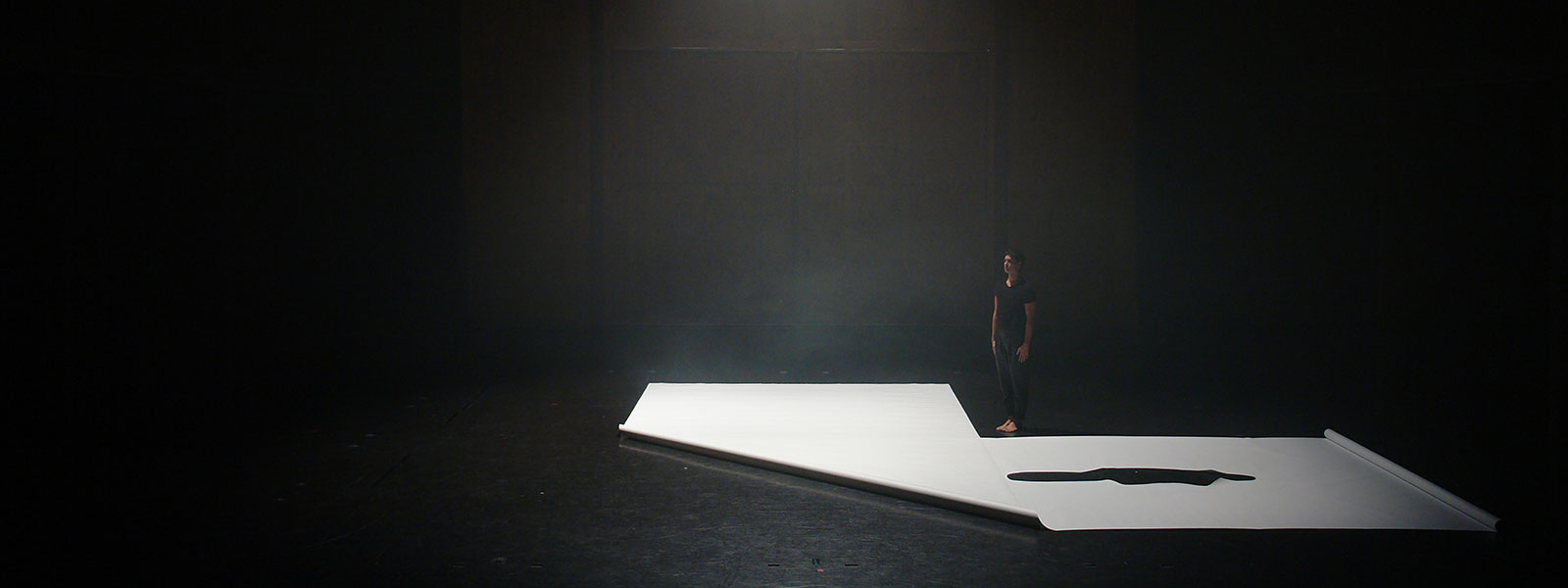

The title dancer-choreographer only captures a small fraction of what Jonah Bokaer actually does. To be sure, he has been dancing professionally for his entire adult life, starting fresh out of UNCSA as the Merce Cunningham Company’s youngest-ever dancer and touring the world before creating his own company in Brooklyn. He is also, however, a trained visual artist who dissolves boundaries between the visual arts and dancing. Not surprisingly, therefore, his choreography has been featured in museums all over the world, often in conjunction with or in response to a particular exhibit.

Finally, in the last 18 years, Jonah has opened two affordable studio spaces for interdisciplinary artists in Brooklyn and an arts incubator in Hudson, NY, where he currently lives. All three arts properties were overseen, structured, and supported by Jonah Bokaer Arts Foundation, with its Board and Staff.

Jonah spoke with Rob Kramer and Pier Carlo Talenti from his home in Hudson. In this interview, he gives us an insight into how he cut his teeth on non-profit leadership and practice starting at the age of 20 while continuing to explore and expand his artistic practice. He also explains how he manages to keep his head above water through unexpected challenges, past and present.

Choose a question below to begin exploring the interview:

- How did you go about leading yourself to find your own vision?

- What did you notice about [Merce Cunningham’s] leadership, and what lessons did you take from that first experience as a young professional?

- How did you lead yourself to explore a visual arts career as well?

- Can you talk a little bit about how your work evolved into an interdisciplinary exploration and what’s guiding that true north for you?

- You mentioned ethnicity early in our conversation and your cultural background. Do you think that informs that spirit you’re talking about now?

- How would you describe yourself as a leader and also as a boss, since you do have staff? And what have you still to learn?

- How are you leading through what is happening currently, and what role do you think arts leaders will have after this episode in our global history?

- Epilogue

Pier Carlo Talenti: Clearly you’ve really beaten your own path in your journey as a choreographer and a visual artist. How did you go about finding your own vision? How did you go about leading yourself to find your own vision?

Jonah Bokaer: I would start perhaps by thanking UNCSA for awarding me a scholarship. I believe I was 15 and allowed to study out of state at UNCSA. That afforded me the chance to specialize in dance, particularly contemporary dance, at that age.

When I was 15-16 years old in that first school year, that was when I felt liftoff, from being very aspirational with dance and the performing arts, yet also somewhat isolated in Ithaca, NY with limited access to training. So this is again a thank you for the educational opportunity that started at that time. What attracted me to UNCSA was the ability to study modern and contemporary dance in depth so vigorously within a high school setting. That remains quite a unique program, and it attracted me to the school.

Perhaps it’s just coming from a very, very large family, growing up with a father who was a North African immigrant, and being the eldest of four boys.

On the student-life front, I found myself poor and without means, but with a scholarship. I think it’s very interesting in hindsight that I quickly became an R.A. at age 17. That’s a small detail, but basically as an adolescent, I was navigating in ways that are still tied to family dynamics. So being the resident assistant, the hall monitor type, I would say with a wink, speaks to leadership orientation in some small way.

Looking back can be humorous but I’ll share with you now, since we’re all adults: What I did is I stopped being a dependent that year, and although these were very small amounts of income, I started filing my taxes on my own that year. So that was something.

Pier Carlo: This is at the age of 17?

Jonah: Yeah.

Pier Carlo: Wow.

Jonah: There were ups and downs, but one of the ups was being afforded the opportunity to enter Merce Cunningham’s company right out of high school. I was 18. So that was a windfall. Also a bit of a fluke, I believe, due to my kind, type, size of body as a dancer. I was also replacing a dancer who may have been Hawaiian — he was actually adopted — and I’m half Middle Eastern, so I really looked the part. At age 18 I was entering a rather dynastic dance company, and it was a large leap.

Merce Cunningham was a leader. In fact, he was a very iconoclastic, deeply prolific, lifelong artist, whom some compared to Shakespeare. His was a truly phenomenal output of work that I was lucky enough to be a part of.

I bring that up not only to talk about careers in the arts only but also to say that he, Merce Cunningham, was a leader. In fact, he was a very iconoclastic, deeply prolific, lifelong artist, whom some compared to Shakespeare. His was a truly phenomenal output of work that I was lucky enough to be a part of.

Rob Kramer: What did you notice about his leadership, and what lessons did you take from that first experience as a young professional?

Jonah: I noticed a very monastic work style, for one. At that time he was 80 years old, and I was 18 years old. I noticed his deeply centered and monastic, measured leadership style. This was not someone who would “freak out,” or blame, or jump to conclusions, or anything of the kind. I noted being exposed to such maturity, across the generations. But it was also intimidating. It was like working with Yoda, a Jedi master. That kind of gravity was not casual, and in fact the opportunity and the job were very demanding.

Another impact on me was to see the leadership of Jeffrey James as the executive director, in particular his work with the board, and his abilities to fundraise. That did mark me. It was a truly legendary board, exemplary, which included some of the elder-most philanthropic families in America. Seeing that come together, when it did, was very powerful.

I set up a nonprofit in a very large loft space of mine in Bushwick, Brooklyn in 2002 — I would have been 20 — and that began as a magpie move given my age at the time. My thinking was, it was about 1,400 square feet of rehearsal space, and 1,400-square-foot loft, which could be used for a variety of programs. At the time Bushwick was in the IBZ, the Industrial Business Zone of urban North Brooklyn — largely Ecuadorian and Yemeni — although there are also active schools and factories. It became known and branded for its industrial grit, but at that time, there was a lot of extremely hardcore crime and danger.

I was leasing the loft and slightly curious, even baffled, about the prospect that dancers, choreographers, and performing artists could benefit from what at the time was free space and then stabilized to become a five-dollar-an-hour space. I wondered, would people venture that far out on the L train, and receive an artistic service or a subsidy? I knew that was what I needed to start early steps into choreography, and I was aware that others needed the same.

I was 20, and becoming a founder is something I continue to think about on a daily basis. How do you be a good founder? Founding the nonprofit in a very urban part of New York City that traditionally had not seen services or funding was a large risk. It was far, far from the perceived center of New York City, but also had challenges of every kind: infrastructure, transportation, social, economic. So I bring up this activity because it happened on an equal, parallel track to a much more well-documented career with Merce Cunningham and modern dance.

That facility still remains. It is still stable, and there are now two others, which are modeled after it.

Pier Carlo: I’m wondering if you can answer the very question that you pose, which is how do you be a good founder?

Jonah: Well, I’m working at it 17 years later, but I do like to speak about nonprofit work as a practice. I don’t know if that resonates, but very frequently in the performing arts, live performance in this country is riddled with scarcity. So in the nonprofit sector, I think about the practice of continuing this work all the time. Thinking of it as a practice, rather than a sector with scarcity, can be helpful.

Pier Carlo: And how did you lead yourself then to explore a visual arts career as well?

Jonah: There’s an untold narrative there, and it could be fun to revisit that, and share it openly. I was saving per diem from touring and using the per diem to pay for night school. [He laughs.] That was the way the allocation was going: basically using what was a livable per diem from dance and theater and then reallocating it to go to art school by night. It took a great deal of patience certainly, and to be transparent with you about the challenges, it took seven years to complete. So it was very intermittent. I attended Parsons and also the New School, where I did a double concentration in Media and Visual Studies.

The backdrop for this kind of study was living-art history with Cage/Cunningham, and later with the Robert Wilson and Philip Glass legacies. Careful savings and then re-allocations were then allowing me to go to night school for seven years. I share that just by way of the fastidiousness that these studies required. And against the more canonical backdrop of those art legacies, there was also the backdrop of Bushwick, and what was going on there with younger practicing visual artists, raw space, installation art and at that time a very raw energy in the visual arts of that neighborhood.

...there was a real contrast or dichotomy between the much more celebrated legacies, and then the more emerging, raw, edgy scene. I guess, to summarize, maybe I was moonlighting between the two.

I bring that up because there was a real contrast or dichotomy between the much more celebrated legacies, and then the more emerging, raw, edgy scene. I guess, to summarize, maybe I was moonlighting between the two.

Rob: Well, what I hear in that is a number of things. There’s a curiosity, it seems, that you have across disciplines. There’s a resilience and sort of stick-to-it-iveness or tenacity to continue through the seven-year process as you described. I’m curious if you can talk a little bit about how your work evolved into an interdisciplinary exploration and what’s guiding that true north for you.

Jonah: Thanks for the interdisciplinary question. I believe earlier on, let’s say in the late 1940s and early 1950s, when these towering artists were encountering composers like John Cage or when Robert Wilson and his loft mates would have been experimenting on Wooster Street, which is where they were based, that the combustibility of artistic encounters was very real and exciting. I think of the sculptors and the choreographers, certainly, but the artists paved the way for a Soho in which crossover art was happening. Then by the 1970s the advent of minimalism was starting to express itself in music and theater as well.

By the time I was involved, they were literally booking the show! [He laughs.] Not to be crass at all, but the participation that I was lucky enough to have was what some have called “The Tail of The Dragon.” There was one year when we signed a 48-week contract as members of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company. These were very successful legacies, though they started as very experimental.

You used the word interdisciplinary. That was really the heart of it for me, seeing that Andy Warhol had been involved and Robert Rauschenberg had been involved. I was most inspired by the adventurous aesthetic appetite. I guess I had wanted to find it in my day, in my place, and in my time, which then was Bushwick and remains Bushwick. The interdisciplinary way of working seemed to me to need a software update, or to be rebooted in terms of its present-day expression.

You mentioned tenacity. That quality involves keeping small performance spaces open. These efforts, so far, have been approximately 75-seat spaces. Some years in, Bushwick had exploded in terms of popularity. When that was combined with the collapse of Lehman Brothers and also Michael Bloomberg’s New York and the development of Williamsburg … we could say there had been a seismic shift in artist workspace at the time, including massive amounts of gentrification along the L train. Zoning shifted, and what had been very edgy artist workspaces became a proliferation of condominiums, with zoning restrictions that had been lifted from five stories to, I believe, 40 stories.

That variance created gentrification and price-point pressures. It also created compression on the mission of our nonprofit, which was to provide affordable space. I ended up being approached by a developer and then by another artist to participate in a second space which paradoxically was further into Manhattan. It was in Williamsburg, which is closer to Manhattan than Bushwick. And because the mission was affordable space, we embarked on that with the Board.

I bring that up because in my 20s it then involved a capital campaign. It ended up being a successful capital campaign, but [he laughs] these were really hair-raising years during the economic crisis of that time. For me, it was a lot about working hand-over-hand with what became a very special Board, which was a working board and later a philanthropic board. I bring that up because it, the capital campaign, was a major marker for us.

Finally, there was the purchase of a facility in Williamsburg, Brooklyn which is still standing. Both facilities are still standing.

Pier Carlo: And this all happened in your 20s?

Jonah: We closed the sale on the Williamsburg facility in January of 2009. Yes. So I would have been 28.

Pier Carlo: That’s incredible.

Jonah: It was a wild ride. It was definitely a wild ride. That also would have overlapped with the fourth quarter of 2008, which was the Lehman Brothers collapse and soon after, the recession. The Williamsburg facility was also developed within a LEED Gold building that became the first building of its kind, size and type in Brooklyn. So I speak about it again from nonprofit practice — campaigning — and from a mission standpoint, which again centers on affordable space.

I realize that the lifecycle of an arts organization often grows from a founder-driven organization to evolving as an institution. I feel honored to have guided that institution through the Williamsburg mortgage, which was retired in January 2019 after a 10-year term. That is a much longer saga to recount and would require focus.

These are the expressions of a first-generation artist, though. I saw my father struggle and have a little bit of a “trampoline" existence. These opportunities presented themselves in my 20s, so I tend to just work like hell to try and make them happen [laughs].

Rob: Would you say that’s just how you’re wired and who you are as a person, or did you develop that sort of energy and tenacity as you matured? Where did that come from for you?

Jonah: I will share, and I think this can stay recorded, that my father experienced bankruptcy when I was growing up. It weighed very heavily on me and on all of his children. But being the eldest, this was a tough inheritance, I would say.

Pier Carlo: How old were you when it occurred?

Jonah: I would have been 13. I didn’t want to digress with that, but having a Middle Eastern father who guided a family through financial hardship probably led to quests such as scholarships, R.A. work, and whatnot. In this case, people have tended to frame my career in terms of an entrepreneurial thinking as an artist. I don’t always see it that way. I see it as an artistic compass and very often a survival mechanism.

Pier Carlo: You mentioned ethnicity early in our conversation and your cultural background. Do you think that informs that spirit you’re talking about now?

Jonah: I think being bi-cultural is complex. I always wish to be accurate. So to present a complete picture, my mother’s American family was deeply immersed in theater and regional theater in the U.S., so that was very present in my upbringing, and I think it helped, in terms of fluency with theater.

Those cultural influences were very palpable, and added flair and negotiation and humor and strength at various times. I do bring that up because it was so formative.

But the cultural side that I tend to identify with is certainly my father and his family, because their foreign culture was in the living room and next door. There was a family restaurant, with North African food. And so those cultural influences were very palpable, and added flair and negotiation and humor and strength at various times. I do bring that up because it was so formative.

Then later on, not only onstage but also while navigating institutions and politics, I can see much later in hindsight how that allowed an adaptability, “the gift of gab” maybe, or being able to understand people from many cultures right away.

Pier Carlo: How would you describe yourself as a leader and also as a boss, since you do have staff? And what have you still to learn?

Jonah: Oh, that’s good, we should go there. I do not know. This is outside the comfort zone, but I think for the first decade being a founder, who then suddenly had employees, with a startup budget, I’m not sure that was a walk in the park for anyone concerned. [He laughs.] Between age 20 to 30, I think the program was, “Can this nonprofit survive?” But in the phases of a nonprofit — and myself included — learning about the economics of this, the function of fundraising, of an annual benefit, of a board, of governing, that was where a lot of my time was distributed. And it still is.

The one thing I can say is the organization makes everything transparent. I think that may come from me, but there is an abundance of communication and a transparency with money at all levels of this organization. That was important to me because it seemed, especially in dance, that a glorification of financial precarity and “Let’s all be in the poor tribe” was an outdated logic.

Dance is never separate from our culture. That is my belief. Dance is never separate from culture.

This goes back to archetypal images from films that have upheld the poor-artist archetype. And that’s valid; why not? But it’s almost a leftover romanticism, whereas in fact, this is a nation with uncommon amounts of capital for cultural production. For example, the entertainment sector in the U.S.: iPod was the first, and then Spotify later; these corporations hire dancers. And GapFit, and the film industry. And more. Dance is never separate from our culture. That is my belief. Dance is never separate from culture.

On staffing, I think I was just applying the same skills while in front of a rehearsal to being good in the front of an organization. That’s all I would have known how to do at that age. If you run a rehearsal well and you’re kind to people and you get it done and you stay on time, people stay happy. I think that that’s what I must have been doing instinctually in an office too. Just with a little bit of heat under me economically [laughing].

I would say that in the last three to five years I’ve calmed down a lot. The capital campaign was challenging, at age 25. I recall it contained a lot of strain, once the recession hit. I was exhilarated but overextended, and there was always a kind of threshold at which things were “too much,” which is not an experience I have kept in the culture of the organization.

Running an organization while also maintaining choreography/visual art crossover work is often enough to fulfill. Our scale and my management style have really walked back, softened, and come into balance, I would say. Which is probably age, but it’s also the realizing that stress is not the goal.

Then a big lesson was finding the people that you trust and delegating. Really, finding the team is the short answer. I think we all mature. We’re always growing.

Pier Carlo: How are you leading through what is happening currently, and what role do you think arts leaders will have after this episode in our global history?

Jonah: I think there is a current butterfly effect that is not subtle. What is happening between COVID-19, the arts, artists, organizations and the economics that tie us together can seem devastating on an hourly basis. To be frank, where my thinking just cannot catch up with this episode is how to solve public assembly and the transmission of live work to live audiences. How are we going to innovate around these challenges? I know there’s a lot of attention on telepresence, Zoom, streaming, and we should keep attention on that. Yet replacing the live is where I just don’t have an easy solution yet, though I’m thinking about it all the time. You may know I’ve dabbled in app development too.

So, COVID-19. I really don’t have any answers, but I am these days full-throttle keeping the organization open. We’ve submitted 19 relief grants as of today’s date.

Pier Carlo: Wow.

Jonah: Yes. Which for our size has been daunting. The team is a little fried these days. We’re remote and adapting at too rapid a pace, including for me.

Pier Carlo: Are you speaking to us from upstate or where are you now?

Jonah: I’m in Hudson, NY, attempting to keep our festival at (or around) Labor Day responsive to this community while also solvent, which I’m pleased to say seems on-track. And I will say we’re financially healthy. The program is fully funded. It’s in escrow, protected.

Pier Carlo: Congratulations. Wow.

Rob: That’s amazing.

We try to remain the right size. I’m trying to stay on track, trying to have good people involved, trying to send good waves through the work.

Jonah: Well, I like to do these little Houdini acts! We try to remain the right size. I’m trying to stay on track, trying to have good people involved, trying to send good waves through the work. Credit should go to the curator on that one: Aaron Levi Garvey. The Hudson Eye is really his curatorial “flex,” and I would hope to grow him as a leader, because I see tremendous potential in him. He’s always a step ahead of the culture.

I’m enjoying this conversation from Hudson where, just on the community side, by being here, staying here, showing up, I think trust is built too.

Epilogue

Few artist leaders we have spoken to for this series seem to thrive quite as well in balancing a strong drive with calm and assuredness. Lessons we can take from our time with Jonah Bokaer include:

- Know your story. Every aspect of your work is there for a reason. Knowing the “why” is as crucial as knowing the “what.”

- Be gracious. It’s easy in the midst of creative growth and expression to forget how to treat others. Treating people with dignity and respect goes a long way.

- Seek possibility. There is always another option to explore, another opportunity to seek. A generative spirit can lead to positive results.

- Keep going. It’s understandable to wind down when times are tough. Staying creative in the face of turmoil takes true courage.

- Be adaptable. As your career grows, it becomes more imperative to successfully lead in all directions — up, down, across and outside the organization.

This written version of the podcast interview was edited for clarity in collaboration with the podcast guest.