Parallel Play: The Vivaldi Project

Author: Kendra Harding

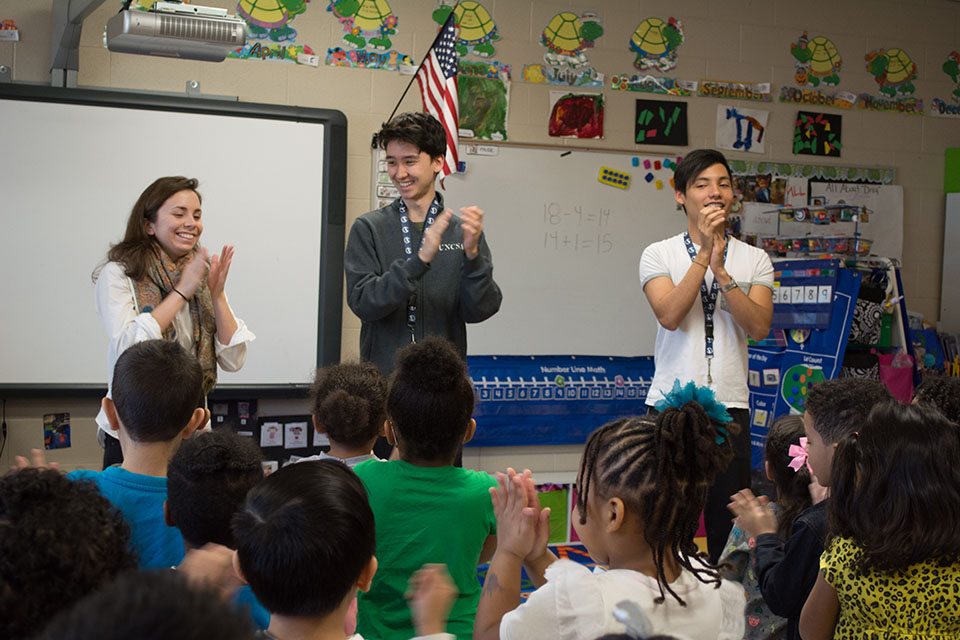

The award-winning Vivaldi Project — named for composer and teacher Antonio Vivaldi — is a violin pedagogy program founded by UNCSA professor Ida Bieler. Vivaldi Fellows are highly-trained student artists, who receive guidance from Ms. Bieler as they begin their journeys in teaching. This ArtistCorps program is currently based at Diggs-Latham Elementary, where six UNCSA students provide group and individual instruction in music and violin to over thirty pre-k students.

I dropped by Diggs-Latham recently to observe the program in action and ask a few questions.

Image Credit: Haydee Thompson

Sarah Harrigan, who joined the program in 2016, likens the experience to the work cosmetology students do. “It’s training for us but we’re doing the practical part of it,” she explains. “It’s also an advantage for the children to be part of it. It’s kind of like hairstylists training to cut hair, and you get it done more cheaply,” she laughs. “I would encourage every school to have this sort of program because it’s the only way we can learn how to teach. We get seminars, but we really need hands-on experience to build upon that. Vivaldi Project has been a vital part of my education.”

The day began in a classroom full of students where Julian Smart – a third-year violin major – and Sarah played Brahms for them. During their performance, one boy caught my eye. He smiled, closed his eyes, tilted his head back, and began swaying back and forth to the music. When they finished, he opened his eyes – still smiling – and enthusiastically clapped for his teachers. To see a five-year-old child absorbed with classical music is part of what the Vivaldi Project brings into these childrens’ lives.

“When we started this year, there were two kids who would walk in and they’d be crying and mopey,” said Delphine Skene, who has been with Vivaldi since the program started in 2015. “Now one of them is the quickest, brightest kid and he loves violin. He’s really curious and wants to learn. He asks questions and wants to understand things.”

This kind of transformation is only possible with the program’s ongoing presence in the classroom. The teaching artists build trust with students, allowing curiosity to thrive. It’s a learning process on both sides, and Julian says he’s grown as a mentor and teacher.

“The biggest thing I’ve learned is how to interact with young people,” he says. “Trying to understand them and be empathetic — to connect with them.”

Delphine agrees, saying that she’s strengthened both empathy and intuition to meet the needs of the students.

“I’ve learned a lot about people and myself and how to fully give yourself to somebody else,” she begins. “I’ve learned to try to understand them and give them what they need.”

She says that it’s important to keep her interactions with the children positive; she wants them to have good memories of the project. “This is something that they can hold onto that’s beautiful. While we focus on building skills, we are mindful that they leave the instruction feeling good about themselves.”

Sarah believes that the program is addressing a critical need for consistency in violin instruction. “Our teacher says we live in an age of confusion in pedagogy, especially violin methods. We teach a simple, systematic approach that works for everyone,” she continues. “A lot of musicians come out of school playing well but they don’t really know how to teach. That’s our job now—to learn to teach well. I don’t think I would know how to without this program."

After Brahms, Delphine led the group in “The Weather Game.” Children volunteered different kinds of weather to go on a map – everything from hail to tornadoes to raining frogs. She helped the children practice the sounds and then moved quickly through them. It was funny to see them wake up over the course of this game. 8:30 AM is early, so the game lagged at the beginning but eventually moved with speed. This perfectly illustrated how quickly the students pick up on new things and begin to make connections, which is a critical component of learning the violin.

“It’s surprising how fast they pick things up,” she says. “We used the alphabet to make a scale one time and they could tell every note using their knowledge of the alphabet.”

“I’ve been thrilled with how much potential these kids have when they’re so young,” Julian adds. “It’s been an interesting process to help instruct this fun, warm, welcoming program with music.”

Delphine says watching the kids absorb these new ideas has been the most rewarding part of her time as a Vivaldi Fellow.

“It’s like building a card castle and you step away and it stands,” she says. “Every time I teach a kid and show them something and I’m not holding the violin or giving them instructions, they’re standing on their own and doing it; that’s really gratifying to me.”

After the weather warm-up, students volunteered to be examples of whole, half, and quarter notes by grouping themselves into groups of two and four, or by standing alone. There was one moment when the students didn’t seem to fully grasp the concept. Then the classroom teacher offered to let the Vivaldi Project use a magnetic apple to further illustrate. Delphine showed the children the whole apple, explaining that it takes a long time to eat a whole apple, less for a half an apple, and even less for a quarter of the apple. She then applied this to the notes, and the activity went on without any additional hitches.

This kind of adaptability and learning on the go is critical to the success of Vivaldi Project and the students. Sarah explains that the program is designed so that the Vivaldi Fellows are learning alongside the children they’re teaching.

“Vivaldi Project works in two ways: we’re learning how to teach and the students are getting all of the exposure to music they wouldn’t normally have,” she says. “The way we evolve and move in parallel together—how we’re always learning from our mistakes— is really special.”

Students were then pulled for individual lessons with the Vivaldi Project members and the pairs went to “breakout rooms.” Tiny violins were stacked up and children stood on folders with their names and “playing position” footprints written on them in marker.

The students I observed showed an array of skill and interest levels. The boy who was enjoying the music so much at the beginning of the day was enthusiastic and played very well during his instruction time. Others required a little more encouragement to find their motivation, something Sarah says she’s learned to do for herself in practice as well.

“I’m trying to move faster with some kids, and trust that if I move fast, they’ll move fast,” she says. “I realized I had to work on that inmypractice, too, to fix problems faster.”

Julian also feels that learning to teach others has helped him develop different practice habits for himself.

“When you’re teaching, you use your brain differently than when you’re playing or performing or learning from a teacher,” he explains. “We’re trying to simplify what we’re teaching them. That ability to simplify translates into my practice. Being patient when I’m teaching has also made me more patient with myself in the practice room.”

The Vivaldi Project team members have grown and changed over their years of service, and hope the program continues to flourish.

“We could make a list of why it’s important!” Julian says. “The first reason is the curriculum; this is developing into something valuable for the school and for the string program here. It’s important to be able to teach your instrument. The other thing is that we inspire and foster appreciation of classical music. We keep the fire burning and keep them interested and by showing them that it’s fun.”

Delphine says Vivaldi Project is really about planting seeds in children’s lives.

“It opens an emotional door—showing them that this exists and they can do it,” she says. “[They] don’t have to do it for the rest of [their] lives, but it’s something that they’ll remember and always be able to go back to because there’s a connection. It plants seeds of possibility.”

Sarah sums the project up well, echoing Delphine’s thoughts:

“If they can find something that’s meaningful to them in the whole process, then we've done our job.”

April 11, 2019